But the changes announced by the university won praise from the ADL’s Jonathan Greenblatt and the school’s Hillel executive director

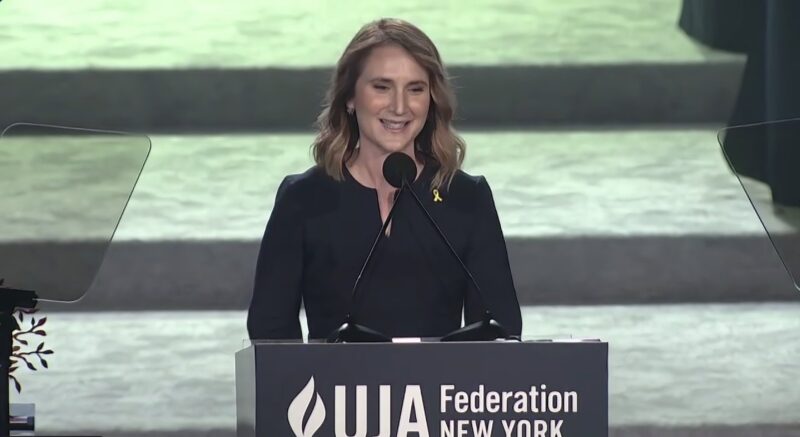

JEENAH MOON/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

Columbia University acting President Claire Shipman speaks during the Commencement Ceremony at Columbia University in New York on May 21, 2025.

As Jewish students and alumni at Columbia University await the final details of the university’s prospective deal with the Trump administration, some are expressing skepticism that a list of commitments announced by the school this week to address antisemitism on campus would have a significant impact on protecting Jewish students.

The steps were publicized Tuesday by Columbia’s acting president, Claire Shipman, as the school works to reach a deal with the Trump administration to restore some $400 million in federal funding that was cut by the government in March due to the university’s record dealing with antisemitism since the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas terror attacks in Israel.

On Thursday, The New York Times reported that about 10 Columbia and Trump administration officials, including Shipman, met in Washington for roughly an hour. The White House confirmed that President Donald Trump has been fully briefed on the meeting but that negotiations were not finalized. According to a draft deal, Columbia would be required to pay a $200 million fine and commit to releasing admissions and staffing data to the federal government.

“The deal as it stands now lets Columbia off the hook relatively without a scratch,” Inbar Brand, who graduated in the spring from Columbia’s dual-degree program with Tel Aviv University, told Jewish Insider. “The school gets its money back without resolving the core issues in its governance and administrative structure that allowed for antisemitism to fester openly for so long on campus.”

“It’s disheartening that after all the pressure placed on Columbia by the Trump administration, they are pulling back exactly when it matters most,” Brand said.

The commitments already agreed upon by the university include further incorporating the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s working definition of antisemitism by requiring its Office of Institutional Equity to embrace the definition; appointing a Title VI coordinator to review alleged violations of the Civil Rights Act; requiring antisemitism training for all students, faculty and staff; and refusing to recognize or meet with Columbia University Apartheid Divest, a coalition of over 80 university student groups that Instagram banned earlier this year for promoting violence.

These diverge from a list of reforms that were demanded in the Trump administration’s letter to Columbia in March, which were initially agreed upon by the university but never finalized. These included putting the Middle Eastern, South Asian and African studies department and the Center for Palestine Studies under the purview of a senior vice provost, who would be appointed by the university to supervise course material and non-tenure faculty hiring; changes to the University Senate, which critics say has blocked discipline against anti-Israel protesters and removed protest regulations aimed at protecting Jewish students; and the formation of a presidential search committee to replace Shipman.

“An immense disappointment” is how Noa Fay, a graduate student entering her last year in Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs, described the university’s latest commitments and prospective deal.

“Adoption of the IHRA definition of antisemitism is the only satisfactory aspect, and even that does not solve what has been the paramount issue at school since Oct. 7 — adherence to and enforcement of our own policies, rules and codes of conduct,” said Fay, a student member of the Columbia-SIPA Anti-Hate Task Force who last year received the Anti-Defamation League’s Levenson Family’s Defender of Democracy Award for her work to combat campus antisemitism.

Fay sees the outlines of a Trump administration deal as “largely symbolic” because it “establishes new policies and bureaucratic measures for reporting antisemitism without requiring Columbia to enact institutional reforms that would guarantee their effectuation,” she told JI.

The only measures that will accomplish a safe climate for Jewish students, Fay suggested, are those that were outlined in the Trump administration’s letter earlier this year, including “discipline [including expulsion] of culpable students and faculty; admissions reform; education and [changes to] the University Senate, as it has served most reliably and forcefully to protect those guilty of antisemitic racism at school.”

Lishi Baker, a rising senior at Columbia studying Middle East history and co-chair of the pro-Israel campus group Aryeh, echoed a call for the University Senate to be stripped of some of its power. “It’s the primary reason our governance is so bad and cannot continue to exist in its current form,” he told JI.

Baker said he’d like to see “a strong deal to restore federal funding in exchange for deep institutional reforms.”

“If we want to change our culture, we need the right structures in place to do so. For example, revealing hiring and admissions data is good but it doesn’t fundamentally change culture. We need to actually hire better, more responsible people, and this might require changing the hiring process,” Baker continued. “We need better policies, better accountability measures and stronger moral leadership. Adding antisemitism to a list of micro aggressions doesn’t do it for me — we have to fix the culture of excluding and litmus testing Jews for their connection to Israel.”

Eden Yadegar, a former president of the Columbia chapter of Students Supporting Israel who graduated in the spring with Middle East studies and modern Jewish studies degrees, told JI that “a deal that abandons reforming the institutions that have fostered antisemitism would be tantamount to abandoning Jewish students.”

“President Trump should not sign a deal of this framework,” Yadegar told JI. She wrote on X that the commitments are “good first steps” but believes her alma mater is “once again vying for a PR win.”

“The strategy?” Yadegar continued, “Elicit praise for quick fixes to pave the way for a deal that abandons the need for structural reform … I’m sick of being expected to praise the bare minimum from Columbia.”

Eliana Goldin, who graduated in the spring as a political science major with a dual degree from the Jewish Theological Seminary, expressed concern that if the steps are “taken as a win, it will distract from actually dealing with Columbia’s deep-rooted issues and can possibly lead to more antisemitism rather than less,” she told JI.

Goldin continued, “Essentially, if you don’t treat a problem at its roots, you might never treat the problem.”

The commitments received praise from Brian Cohen, the executive director of Columbia/Barnard Hillel – the Kraft Center for Jewish Life, as well as Jonathan Greenblatt, CEO of the ADL.

Cohen welcomed the steps taken by the university, “including the unequivocal recognition that there is an antisemitism problem on campus and that it has had a tangible impact on Jewish students’ sense of safety and belonging,” he wrote on X. “I hope this announcement marks the beginning of meaningful and sustained change,” said Cohen.

ADL chief Greenblatt wrote on X, “I applaud these commitments made by @Columbia, which will help restore the university as a welcoming place for Jewish and Israeli students and faculty.”

“Our hope is that Columbia can go from being an example of the worst of antisemitism on campus to being a model for what other colleges can do to combat antisemitism,” Greenblatt said.

While Trump has not yet responded to Columbia’s latest commitments, last week he told CNN that a deal was likely to happen. “We’re going to probably settle with Columbia. They want to settle very badly. There’s no rush,” Trump said.