The group’s annual conference, being held in August, features a panel that describes the Oct. 7 Hamas terrorism as attacks on ‘military targets’

Graeme Sloan/Sipa via AP Images

A general view of the American Psychological Association headquarters in Washington, D.C. on April 23, 2020.

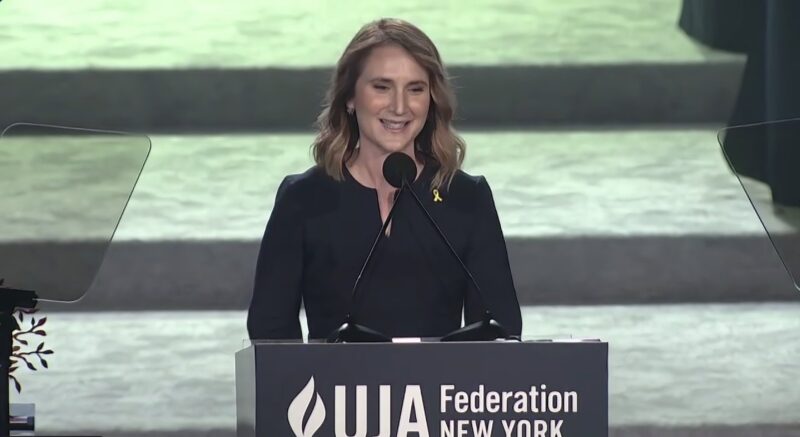

In late February, Dr. Julie Ancis drafted an open letter with a group called Psychologists Against Antisemitism, condemning antisemitism within the American Psychological Association. More than 3,500 people signed on to demand the organization act against what they described as “the serious and systemic problem of antisemitism/anti-Jewish hate” within the APA. With 172,000 members, it is the largest body dedicated to the study of psychology in the world.

For months, the organization appeared to do nothing. Ancis did not even get an acknowledgement that the letter had been received. But then in May, after she and another Jewish colleague raised their concerns in a meeting with Rep. Ritchie Torres (D-NY), Ancis received an invitation from senior APA officials to discuss antisemitism.

The meeting was ostensibly meant as an olive branch from the organization where she had once been a prominent member: In 2010, a division of the APA named Ancis, a distinguished professor at New Jersey Institute of Technology and one of the pioneers of the psychology field’s approach to diversity, equity and inclusion, its Woman of the Year.

Yet when Ancis looked at the list of stakeholders invited to the Zoom meeting, she was astonished to see the names of several APA groups that she considered the biggest perpetrators of antisemitism within the APA. Later, she learned that the list of invited “stakeholders” included Dr. Lara Sheehi, the president of an APA division focused on the study of psychoanalysis, who was called out in the open letter for describing Zionists as “genocidal f**ks.” (Sheehi, who left a teaching position at The George Washington University in 2024 after being accused of antisemitic conduct by some of her students, recently appeared on a podcast to defend the tactics of the man accused of shooting and killing two Israeli Embassy staffers outside the Capital Jewish Museum in Washington in May. She did not respond to a request for comment.)

“The stakeholders should include people who have expertise, not the ones who are promoting antisemitism, where we’re tokenized. It’s an absolute lose-lose situation, and hostile,” Ancis said last week. She decided not to attend. “I’m not going to sit in that farce of a meeting.”

That the APA would host a meeting about addressing antisemitism where the “stakeholders” included both Jews who have scrupulously documented harassment and bias within the organization’s ranks for months, as well as some of the people they identified as the perpetrators of that harassment, is, according to Jewish psychologists, evidence of how this historic organization has lost its way and ceded its moral voice.

“Could you imagine APA having a listening session for LGBTQ+ individuals, which includes people who are known to be homophobic?” asked Dr. David Rosmarin, director of the Spirituality and Mental Health Program at McLean Hospital in Massachusetts and a Harvard Medical School professor. “They want everyone to be included, and all that kind of stuff. What that means is that there’s no room for Jews, because they’re including people who are engaged in antisemitic, anti-Zionist rhetoric, publicly, in the discussions.”

“They’re between a rock and a hard place. They’re trying to appease different constituents, and I feel like they’re appeasing the ones who are loudest and bigger, and that’s not the Jewish professionals,” Dr. Julie Ancis told JI.

Several leading Jewish psychologists told Jewish Insider in interviews last week that the APA has repeatedly failed to respond to the concerns of its Jewish members, despite a stated commitment to promoting an “accessible, equitable and inclusive psychology that promotes human rights, fairness and dignity for all,” according to the organization’s diversity mission. They say the APA has avoided taking a stand against double standards and litmus tests applied to Jewish psychologists who are vilified for their support for Israel.

Instead, the organization has been almost paralyzed in the aftermath of the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas terror attacks and ensuing war, seemingly afraid to take sides between the Jewish psychologists seeking support and an increasingly vocal contingent of anti-Israel voices in the field, some of whom have described Zionism as a pathology to root out.

“They’re between a rock and a hard place. They’re trying to appease different constituents, and I feel like they’re appeasing the ones who are loudest and bigger, and that’s not the Jewish professionals,” Ancis told JI.

The APA is the key body shaping the education of psychologists in the United States. It accredits masters- and doctorate-level academic programs at hundreds of universities across the country. So while the battle over antisemitism in this organization may seem like an internecine ivory tower fight, the way it is handled is poised to have major implications for the future of psychology — a field that touches the millions of Americans who see a therapist, and whose research shapes the way we understand each other and ourselves.

*****

Concerns about antisemitism in psychology have followed the APA since soon after Oct. 7, when the Association of Jewish Psychologists chided the organization for issuing only a tepid statement about the Hamas attacks. “We … are deeply disappointed and terribly saddened that our professional association could not more forcefully and unequivocally condemn the horrific acts of barbarism against the Jewish people of the State of Israel,” they wrote at the time.

The issue has become a flashpoint again this year in the run-up to the APA’s flagship annual conference, which will be held next month in Denver.

Among the events at next month’s gathering, which is expected to draw several thousand people, is a “critical conversation” called “truth-telling as resistance” focused on understanding the 2024 encampments amid “a global and national effort to distort realities about Palestine and the encampments.”

At a symposium about “resisting anti-Palestinian racism,” psychologists can earn continuing education credit for attending a talk that will discuss “advocacy and actions to resist anti-Palestinian racism” that are “erroneously framed as antisemitism.” Another symposium, focused on mental health during wartime in Gaza and Lebanon, features a talk by a presenter who describes the Oct. 7 terror attacks that killed more than 1,200 people as attacks on “military targets” in Israel.

“What concerns me most are the psychologists who are maybe not Jewish or maybe not aware of these concerns in the Jewish community, who attend these talks with what I consider to be antisemitic rhetoric, and accept and internalize the ideas and rhetoric as true,” said Dr. Caroline Kaufman, a post-doctoral fellow at McLean Hospital. She will be speaking at a symposium about antisemitism, which also offers continuing education credit. “When they treat Jewish clients, or they have Jewish colleagues, or they conduct research, those ideas continue into those endeavors. That is extremely concerning to me.”

Rosmarin, a colleague of Kaufman’s at McLean, put a baseball hat over his yarmulke at last year’s APA convention in Seattle because it didn’t feel like a “safe space,” he said. He worries the organization does not understand the scope of the problem. “This is like a cancer that’s spread throughout the organization,” said Rosmarin, who is also the president of the APA Society for the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality.

*****

The term “gaslighting” — a form of emotional abuse in which one person falsely and repeatedly tells another person that their experience of reality is untrue — has become so popular in recent years that it was named Merriam-Webster’s word of the year in 2022. A growing body of psychological research is devoted to studying the concept, which the APA defines as “manipulat[ing] another person into doubting their perceptions, experiences or understanding of events.”

Given psychology’s deepening understanding of gaslighting, it was particularly ironic that following the APA’s antisemitism meeting, which occurred last Thursday, an email discussion broke out in which several psychologists attempted to invalidate and refute the concerns their Jewish colleagues raised about antisemitism. (The email thread was viewed by JI.)

One psychologist referred to the substance of the Zoom call as “propaganda” and said he would denounce only “actual antisemitism.” Dr. Karen Suyemoto, who chaired the APA’s task force that developed guidelines for addressing race and ethnicity in psychology, agreed.

She called it “imperative” that “actual antisemitism” be addressed, because “the continuing confounding creates barriers to allies and accomplices who do not have [a] nuanced understanding.” (Suyemoto, a University of Massachusetts professor, declined to comment to JI. She was the guest editor of a recent special issue of the APA’s flagship journal that focused on “practicing decolonial and liberation psychologies,” which the Anti-Defamation League, Academic Engagement Network and Psychologists Against Antisemitism criticized in a Tuesday letter as “ethically compromised and biased.”)

To Jewish psychologists, the skepticism from professionals who claim to listen to marginalized communities did not add up.

“We take identity very seriously. We realize that it intersects with both risk and protective factors,” said Kaufman. “That’s a given in our field, and APA seems willing to recognize that for several identities or groups. But it’s seemingly unwilling to address such concerns for the Jewish community. I can’t understand why.”

In 2007, the APA adopted a resolution on antisemitic and anti-Jewish prejudice that detailed modern manifestations of antisemitism alongside a commitment to being a leader in fighting it. (The resolution had the foresight to note that 21st-century antisemitism “may be more difficult for its perpetrators to identify and challenge, as their beliefs about themselves may be that they are not biased against Jews.”)

But since Oct. 7, a vocal group of APA members has been encouraging the organization to revisit this resolution because of its assertion that antisemitism can arise in the context of criticism of Israel. An activist group called Psychologists for Justice in Palestine drafted a petition last year calling on the APA to “refute” that part of the resolution — and instead admit that it is actually “discriminatory” to refer to anti-Zionism as a form of antisemitism.

“With the removal of the claim that criticism of Israel can become antisemitic, it would open psychologists to even more experiences of antisemitism and even more antisemitic aggression, by which Jewish and Israeli psychologists can be excluded, denigrated and denied for reasons that are presumably having to do with Israel, but, from my perspective, are really just antisemitism,” warned Dr. Caroline Kaufman, a post-doctoral fellow at McLean Hospital.

The petition was endorsed by several APA affiliates, including the Asian American Psychological Association; the American Arab, Middle Eastern and North African Psychological Association (AMENA-Psy); and the Society for the Psychology of Women. AMENA-Psy — one of six official APA ethnic associations — declared just four days after the Oct. 7 attacks that the group stands “in full solidarity with our Palestinian siblings in their decolonial struggle for justice.”

The APA ceded to the groups’ demands and agreed to reopen the debate about the 2007 resolution. The APA’s board of directors even created a task force to update the resolution. But the effort was shelved in March, as internal criticism of the organization’s handling of antisemitism began to mount.

“With the removal of the claim that criticism of Israel can become antisemitic, it would open psychologists to even more experiences of antisemitism and even more antisemitic aggression, by which Jewish and Israeli psychologists can be excluded, denigrated and denied for reasons that are presumably having to do with Israel, but, from my perspective, are really just antisemitism,” warned Kaufman.

*****

The solutions that Jewish psychologists seek require a long-term commitment from the APA that they aren’t confident they will receive, although the organization’s leaders stated on last week’s call that they do want to do more to combat antisemitism.

The concerned Jewish members want stronger monitoring on APA-affiliated email servers, which have been used by some APA members to promote boycotts against Israel and, occasionally, to defend Hamas. (An APA spokesperson told JI that “enhanced oversight is now in place to ensure respectful discourse and timely response to violations.”) They are also seeking more stringent oversight of the panels at the summer conference.

“They still struggle to really make a determination as to whether or not anti-Zionism is antisemitism, and so I surmise that people could say some things that would be very hurtful to large swaths of the professional community, and it would be considered acceptable within the new and refined listserv guidelines,” Fordham psychology professor Dr. Dean McKay told JI after last week’s antisemitism Zoom. “That’s one of those places where I don’t think they really know what to do.”

The APA frequently invokes bureaucratic red tape in response to these concerns by asserting that the 54 divisions that fall under the APA umbrella — on topics including developmental psychology, clinical psychology and pediatric psychology — operate autonomously, allowing the APA to claim immunity from the most egregious issues.

“APA’s 54 divisions operate autonomously with their own governance structures,” Kim Mills, the APA’s senior director for strategic external communications and public affairs, told JI in a statement. “Each of them program convention sessions that their leaders believe best represent the concerns of their division and will foster academic discourse on a variety of psychology topics.”

Mills asserted that the APA “unequivocally condemns antisemitism in all its forms and acknowledges the climate of fear such prejudice creates,” and said the organization is “committed to fostering an environment where members of all identities can contribute fully, safely and without discrimination.”

Jewish psychologists are waiting to see if that commitment passes the stress test, but they are not confident. Because while they see general proclamations about the ills of antisemitism as helpful, the true measure of whether the APA is serious about taking on the problem is whether the organization is willing to call out the most extreme members in its ranks, some of whom hold high-profile leadership positions. Doing so would require the APA to wade into the fraught conversation about whether the tactics of anti-Zionist activists can cross a line into antisemitism. It is clear the APA wants to avoid doing that.

“They still struggle to really make a determination as to whether or not anti-Zionism is antisemitism, and so I surmise that people could say some things that would be very hurtful to large swaths of the professional community, and it would be considered acceptable within the new and refined listserv guidelines,” Fordham psychology professor Dr. Dean McKay told JI after last week’s antisemitism Zoom. “That’s one of those places where I don’t think they really know what to do.”

The APA’s diversity webpage features a large section dedicated to explaining antisemitism. However, it does not mention Israel, Hamas or the post-Oct. 7 spike in antisemitism. Nor did Mills refer to Israel or Zionism in a lengthy statement she sent JI last week outlining the organization’s pledge to fight antisemitism. In fact, she ignored a question about Jewish psychologists who feel they have been targeted for being Zionists.

*****

The Jewish psychologists raising concerns about antisemitism in their field know that doing so entails a risk. They worry about the silencing effect on younger Jewish psychologists who are still finding their footing in the field, which is already in a precarious situation amid federal funding cuts to scientific and medical research.

“I’m protected. I’m already mid-career,” said Rosmarin, the Harvard Medical school professor. “I’m animated about this because I care about the next generation.”

Ancis, who spearheaded the open letter to the APA, quit the organization three years ago. She is far enough along in her career to not worry about facing backlash for supporting Israel and speaking out against antisemitism. But she worries about younger people in the field.

“A person coming up trying to get tenure in an APA-accredited program and identifying as a Zionist, I think it’d be extremely difficult,” Ancis said.

Kaufman only completed her Ph.D. four years ago, and she is at the beginning of what she hopes is a career in academia. She has the right credentials: a postdoctoral position at Harvard, an internship at Yale, a speaking slot at a symposium at next month’s APA conference. But she worries that won’t be enough to shield her.

“I have very deep and sincere concerns that my involvement in these issues related to antisemitism will negatively impact the opportunities available to me and my career,” Kaufman told JI. “I hold that truth or that fear in one hand. The other truth in my other hand is that I have a responsibility as a Jewish psychologist to raise my voice and become involved in this issue. There’s truly no other path for me, even if, and I think there will be, serious consequences.”