The inspiration for Joshua Henkin’s ‘Morningside Heights’ is close to home

The author’s new novel about a family confronted with early-onset Alzheimer's echoes his father’s battle with the disease

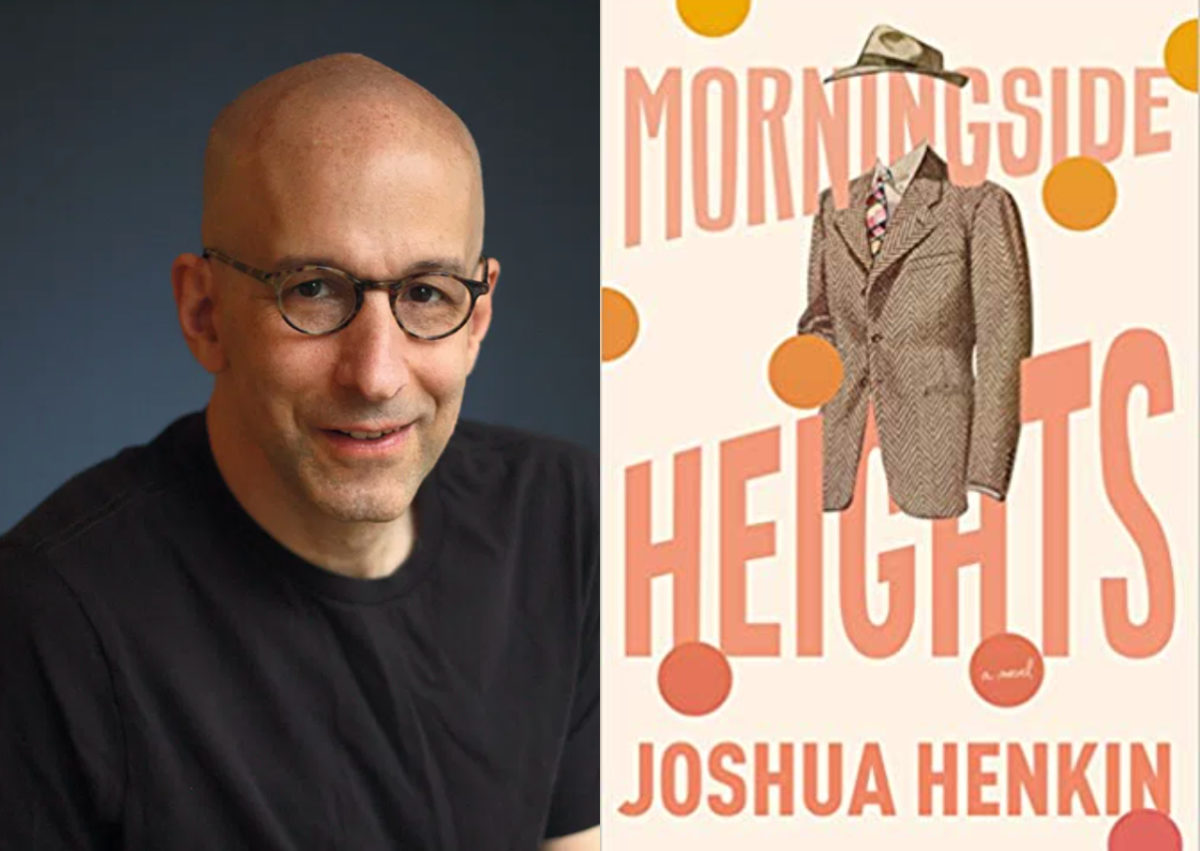

Michael Lionstar

Joshua Henkin

For Joshua Henkin, wrestling Morningside Heights, his newly released fourth novel, to the ground has been a long personal journey that spanned eight years and 3,000 pages of drafts.

The book, billed as “a poignant, illuminating portrait of marriage,” by The Wall Street Journal, tells the fictional story of Pru Steiner’s marriage to Spence Robin, a brilliant Columbia University professor, who is diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s. Focusing mostly on Spence’s family, Henkin gives color to a clan navigating a challenging disease and complex relationships.

Spence’s character, a MacArthur “genius” grant recipient who teaches Shakespeare at the Ivy League school, is closely modeled after Henkin’s late father, Louis Henkin, who taught law at Columbia (which is in the Morningside Heights neighborhood of Manhattan) and also developed Alzheimer’s, albeit later in life than Spence. After Henkin’s mother attended a session for caregivers at the local JCC, Henkin, who teaches writing and runs the master of fine arts program at Brooklyn College, began writing a novella that drew on imagined conversations from that class; that work, many permutations later, became Morningside Heights, which is published by Pantheon.

Henkin told Jewish Insider that writing about the disease presented him with a new challenge: “Fiction has to familiarize the unfamiliar and defamiliarize the familiar,” Henkin explained. Books about Alzheimer’s can be complicated because the course of the disease is predictable; instead of focusing on the illness, Henkin chose to write about family relationships enduring in the face of an unrelenting disease.

Writing fiction based on personal experience presented new dilemmas for Henkin, the author of three previous novels including Swimming Across the Hudson, Matrimony and The World Without You. He was initially resistant to introducing a love interest for Pru, which deviated from his family’s experience. “My mother remains extremely loyal to my father 11 years after my father died,” Henkin told JI. In writing a new romantic attachment for Pru, he feared that his mother would feel uncomfortable about her stand-in character’s actions. But after friends convinced him Pru’s faithfulness seemed unrealistic in fiction and after a phone conversation with his mother, who gave her blessing to this new, unexpected plot twist, Henkin decided to include a storyline about a relationship with a second man.

By incorporating a secondary romance for Pru, Henkin explores a grieving wife’s torn emotions and what he now considers the “false dichotomy” between faithfulness and disloyalty: While Pru is not completely faithful to Spence, she remains loyal in many ways, always prioritizing his care and never abandoning him. “The question of loyalty is much more complicated than I thought before I wrote this,” Henkin reflected.

The book’s title harkens to an era when the poorer neighborhoods of Manhattan’s Upper West Side bore “meaningful differences” compared to the wealthier Upper East Side. “The neighborhood was a character in the book in a certain way,” explains Henkin.

As Spence’s health declines, the neighborhood gentrifies, and as the book progresses, the city’s landmarks evolve.

“I grew up in Morningside Heights and I went to Ramaz [a Modern Orthodox day school] on the [Upper] East Side of Manhattan,” Henkin reminisced. “I was the son of intellectuals and the relatively poor kid at a wealthy school where my friends had TVs in every room in their apartment and we had a lot of books and a TV we kept in the closet.”

The early portion of the novel pays homage to the Morningside Heights of Henkin’s youth, where Louis Henkin would be recognized on the street by other academics familiar with his legal work. In other areas of Manhattan, the elder Henkin’s appearance would not elicit the same response.

At the same time as Henkin’s characters are navigating health issues and interpersonal relationships, they also grapple with their Jewish identity, reflecting the complex tensions of Jewish practice in contemporary America. Pru’s father is Orthodox, while her mother is less religious. Although Pru had a certain disdain for organized religion growing up, she remained observant until marrying the secular Spence, after which her religious practice dwindled. Pru and her mother return to synagogue several times throughout the novel, reflecting on their former religious lives and their new religious identity.

Henkin explained that the inspiration for the religious tensions portrayed in the novel came from a familiar place. “I grew up in a complicated Jewish home,” he explained. Henkin’s grandfather was Rabbi Yosef Eliyahu Henkin, a rabbi so widely respected in the Orthodox community that Henkin jokes his last name earns him free meals in certain circles. “My father was frum until the day he died, and my mother grew up in a Reform family and was much more secular,” he added.

Henkin attended The Ramaz School from kindergarten through 12th grade and spent his childhood summers at the Conservative movement’s Camp Ramah in the Berkshires. His early adulthood included both a stint at a yeshiva in Israel and summers in Colorado, where he was “the only Jew anyone had ever met.” The confluence of Henkin’s experience provides a rich discussion of Jewish identity in Morningside Heights.

Henkin traces his career as a novelist to a job at Tikkun magazine as the first reader of fiction manuscripts, where he pored over many submissions that did not make it to publication. “I didn’t necessarily think I could do any better, but I felt inspired. I thought if other people were willing to try and risk failure, I should be willing to risk failure too,” Henkin explained. He abandoned plans to pursue a Ph.D. in political science and began writing, eventually moving to Ann Arbor, Mich., to enroll in the University of Michigan’s MFA program.

Explaining the task of the novelist, Henkin says, “Messages are for rabbis and priests and political scientists and philosophers and politicians. For me, fiction is irreducible and it’s about making characters jump off the page, and setting them out in the world and getting them into trouble.”

Growing up, Henkin’s parents never pushed their children to pursue high-paying careers. His parents, both trained lawyers, did not practice law: his father taught law and his mother worked in human rights, running the Justice and Society seminars at the Aspen Institute and serving on the board of Human Rights Watch. Unbound by the expectation that he would enter a profession that would require extra years of study and advanced degrees, Henkin felt free to pursue writing. Like their father, Henkin and his two brothers are all teachers.

Morningside Heights was slated for release during the coronavirus pandemic, but had its publication delayed. The time in lockdown allowed Henkin to move past Morningside Heights and write the first draft of a new novel. He is currently at work on two more books, as well as a collection of short stories.

About the “character” who formed the inspiration for his new novel, Henkin reflected, “[My father] was very supportive of my work and he was less of a fiction reader than my mother is, but I think he would have taken [the book] for what it is… I like to think he’d have been happy or proud.”