Adam Serwer on the ‘Jewish divide’

In his new book of essays, the ‘Atlantic’ writer meditates on a tension, exacerbated by Trump, between American Jews and their Israeli counterparts

Shorenstein Center, Harvard University

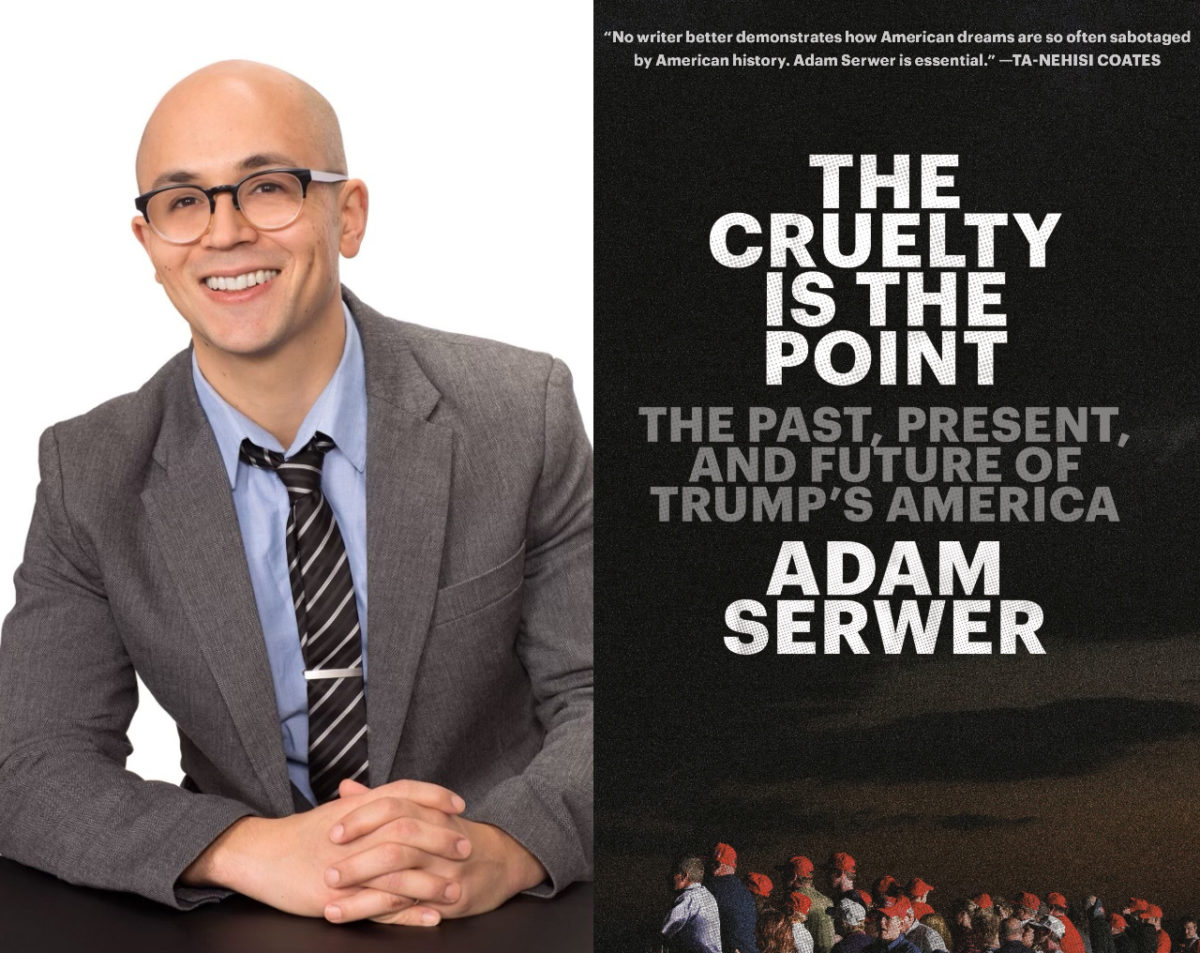

Adam Serwer

In his new book of essays, The Cruelty Is the Point: The Past, Present and Future of Trump’s America, released this week by One World, the journalist Adam Serwer, 39, examines what he views as a central, abiding tension between former President Donald Trump and the American Jewish community.

While Trump repeatedly touted his administration’s achievements in the Middle East during his time in office — including relocating the American embassy to Jerusalem, recognizing Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights and brokering a series of historic agreements between Israel and a number of Arab nations — the former president was often frustrated to find that the majority of American Jews did not support him.

Trump, who was closely aligned with Israel’s then-prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, viewed this dynamic as unconscionable. “I think any Jewish people that vote for a Democrat, I think it shows either a total lack of knowledge or great disloyalty,” he huffed to reporters in 2019, using language that was widely criticized as antisemitic.

Serwer, a staff writer at The Atlantic, argues that liberal Jews in the United States resisted Trump’s entreaties, notwithstanding his effort to cast himself as a champion of Israel, because the American Jewish civic tradition is rooted in an ethos of liberal pluralism that was fundamentally at odds with the former president’s political project.

“Trump’s enthusiastic reception from the Israeli right misled him into believing that American Jews would be a natural addition to his nationalist coalition,” Serwer writes. “But the majority of American Jews, despite their support for Israel, identify with the cultural and political pluralism that has allowed them to live relatively safe and prosperous lives in the United States.”

That dynamic underscores a broader tension, Serwer says, between American Jews and their Israeli counterparts — what he refers to as “the Jewish divide.”

“Trump and Netanyahu’s relationship,” he writes, “forced American Jews to confront the contradiction between the pluralism they support at home and the Jewish nationalism they have made peace with abroad.”

Serwer, who is Black and Jewish, addresses this issue with a sense of urgency supported by a deeply informed historical perspective that is typical of his writing, which often focuses on the intersection of race and politics.

“What I can do is offer a historical argument for why pluralism became so central to the political identities of American Jews and why it remains so resistant to pressure from the conservative movement and from their Israeli cousins abroad,” he writes. “Seeing that commitment as a kind of weakness and failing to appreciate how well it has served American Jews is one reason why its opponents have not succeeded in undermining it.”

In a recent interview with Jewish Insider, Serwer expanded on that topic and more. The interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Jewish Insider: I want to focus on the essay in your book about what you refer to as the “Jewish divide.” I thought it was interesting and made note of some choice quotes I might mention. But I’m wondering, first off, what motivated you to take on this subject?

Adam Sewer: That essay was actually started years ago when Trump first made his comments about Jews being disloyal for not being more supportive of Israel as he understood that. But I never quite finished it because there was a lot that I felt like I wanted to say in it, and so I decided to put it in the book. It gave me more time to think about it and more carefully approach the subject.

JI: Were the ideas that you put forth in the essay floating around in your head for a while, or did you kind of bear them out as you were writing?

Serwer: As I write in the piece, I think, like a lot of American Jews, my feelings about the situation in Israel and Palestine have evolved with the political situation there — and that the political discourse in the United States has not, in my view, really reflected Jewish diversity of opinion on the subject.

JI: Why do you think that is?

Serwer: On the political level, because Americans in general are so supportive of Israel and both parties tend to be very supportive of Israel, the perception is that this is as a result of what American Jews think about Israel, which I feel is not actually the case. And Trump’s unqualified support for the Netanyahu government was revealing in the sense that it showed that what American Jews thought on the subject was not really what was driving American policy.

JI: In the essay you hit on an interesting historical undercurrent that I was unaware of — how liberal pluralism is embedded in the Jewish American ethos, which you suggest has made Jews sort of impervious to invocations from the right. I’m not sure if you agree with that characterization, but the history you brought up was enlightening.

Serwer: That was why I wrote that essay, because I feel like, very often, liberal Jewish pluralism is presented as a sort of weakness or squishiness by our right-wing counterparts, and I wanted to show that it has actually been historically a source of strength for American Jews that they found in allying with other people who are maybe unlike them but who have convergent interests. They’ve found strength that way. It’s a question of idealism, but it’s also a question of pragmatism. But what it is not is a reflection of weakness or naïveté, and the history there was meant to illustrate that.

JI: Jews have not necessarily had it easy in the United States, facing discrimination, violent attacks, education and immigration quotas. Why do you think that American liberal Jews gravitated toward this certain notion of pluralism while, as you seem to argue in the book, the same thing doesn’t seem to have happened in Israel? Israelis are surrounded on all sides and may have a different mentality than American Jews, of course, but American Jews have also, in many ways, experienced a sense of being hemmed in.

Serwer: I think that’s partially what the essay is about. I think what you’re seeing in that divergence is just a fundamental difference in strategies for survival that are both the outgrowth of and have produced a different ideological sense of values.

JI: On a personal level, as a Jew, how would you describe your connection to Israel? Have you been?

Serwer: My grandmother spoke fluent Hebrew and Yiddish, and lived in Palestine under the mandate. She had a very strong personal connection to Israel, both in a spiritual sense and as an ideological project. The last time I went was at a very different time politically for Israel. It was in the early aughts. I think, like most American Jews, I was raised with what I would describe as a liberal Zionist background. My current position is that I favor any settlement that leads to full political rights for all people between the river and the sea, and I am agnostic as to what format that takes, whether it’s two states or one state, as long as it does not result in further violence or denial of fundamental rights.

JI: And what were your thoughts on the recent conflict between Israel and Hamas? It’s been a divisive issue within the Democratic Party and within the Jewish community. It seems to have altered the dialogue on Israel, at least a bit, in American politics.

Serwer: I think that the conflict necessarily exposed certain contradictions about American Jews by and large strongly opposing Trump on the grounds that they do not want to live in a country where citizenship is defined by race or religion and, as a result, questioning their support for a country that has formalized its identity as a nation state for a particular group of people and that continues to deny political rights to another group of people under its authority.

JI: One thing that I had in mind while I was reading your essay was the new unity government in Israel, which I know you couldn’t take into account while you were writing — and obviously Bibi still remains a powerful force in Israeli politics. But what do you make of the diversity of the new coalition? Do you think it bodes well for the type of future you’d like to see in Israel?

Serwer: There are people who cover Israeli politics professionally who are unable to handicap the political situation in Israel, so I will not even make an attempt. But I will say, and what the book is substantially about, is that very often in a democracy, religious and ethnic minorities play a very important role in ensuring that countries live up to their stated values. So to the extent that Ra’am’s involvement in an Israeli governing coalition for the first time can bring the conflict to a just end, or may push the situation in that direction, I think that’s a positive development, and I hope that’s the case.

JI: You said you grew up with the values of liberal Zionism. Would you still characterize yourself as a Zionist, or do you reject the term now?

Serwer: As I said earlier, I support full political rights for all people, Jews and Palestinians, between the river and the sea, and I’m agnostic as to what arrangement that takes. I don’t have a personal preference. To me, it’s what the people there want and can live with in a peace that is just. But even though I was brought up that way, I no longer feel like it’s my place to decide what that arrangement should look like, or to defend a particular arrangement that the Israeli government would like to see.

JI: I thought it was kind of interesting that you bring up Reps. Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib and the effort by some on the right to cast them as antisemites. But you also seem to suggest in the book, sort of disapprovingly, it seems, that Trump has also echoed Omar’s talking points. The implication, as I understand it, is that Omar and, I guess, Tlaib are not undeserving of criticism. I thought you made an interesting point with this quote: “A left that treats anti-Semitism the way the American right treats racism, as a largely imaginary phenomenon exaggerated by bad-faith actors, is a left that has failed to oppose bigotry in all its forms.”

Could you expand on that? It does seem as if the left sometimes dismisses legitimate accusations of antisemitism, and I’m curious if you have any thoughts on what’s going on there.

Serwer: I think there are a lot of complicating factors here. One is that, for American Jews, despite antisemitism that they face in the United States, the primary dividing line in the United States has always been the color line, and that has been more accepting of American Jews than the antisemitism of old Europe. With Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar, whenever they are criticized, they come in for an avalanche of racism and anti-Muslim invective. Nobody is above criticism, and they have apologized for things that they’ve said. But the apprehension comes from the fact that nobody wants to be responsible for making them targets of incredible hatred, which they are constantly being faced with both online and in general.

I think that there are times when the left is too dismissive of antisemitism precisely because it does not fit into the ideological frame that American politics has usually tilted on — that is, the question of the color line. And that’s a real problem. But I don’t think it’s an insurmountable problem. And it does not surprise me that American Jews want to be — or liberals in general want to be — very careful about how they criticize Omar and Tlaib, even when they think they’re wrong, because they want to make sure that they are not aiding what is fundamentally a gross, racist hate campaign against them that is being waged by the right. They symbolize populations that Trump, in particular, demonized, and so nobody wants to be involved in assisting efforts to set them apart from American citizenship, as much of the rhetoric often does, for condemning them on the basis of their ethnic background or religion.

That’s the way these attacks on Omar and Tlaib are often framed — that their citizenship is conditional and that they should be grateful for being allowed to be here or something as though they’re not as American as everyone else. And it is very understandable to me that liberal Jews do not want to amplify that, even when they have criticisms of things that they’ve said or done that they want to make. And that is a difficult tightrope to walk.

JI: How do you navigate that? Do you have thoughts on the way in which legitimate criticism can be leveled but without sort of instigating racist attacks?

Serwer: I think it’s basically impossible to do on social media, but I think it is possible to do in other mediums. Social media is just not a place for nuance. It’s a place where people blow fire at each other.

JI: Are you observant? What’s your denomination?

Serwer: I’m a Reform Jew.

JI: I read in a separate interview that you go to temple more than just on the High Holidays.

Serwer: I do. I pray. I believe in God. My faith is very important to me. It would be very difficult for me to do my job and sort of be in the world without it.

JI: Has your connection to Judaism deepened as you’ve grown older?

Serwer: It was inculcated in me at a young age. But I think that it definitely became more important to me as I got older. But I don’t think I ever really felt like it was not important. I just think when I was in my early 20s, I was not quite as disciplined about going to temple.

JI: How does it inform your politics? Are you speaking for yourself in this new essay, where you describe the American Jewish connection with liberal pluralism?

Serwer: I certainly feel connected to that tradition. But in the essay, I am trying not to describe necessarily my perspective of what I understand about the American Jewish community from our history and from public opinion surveys. Obviously, my position on Israel is not the mainstream one in American Judaism at this point, and I’m well aware of that, and I don’t want to represent it that way. So in the essay, I don’t. The piece is meant to describe a dynamic that I think is occurring in the Jewish community without imposing and describing what I think about that dynamic, without imposing my own positions on other American Jews, if that makes sense.

JI: In terms of the history you examine, I thought the look at antebellum Charleston was interesting, as were the details about Jewish slave owners and abolitionists. What was the process of researching that like for you?

Serwer: I spend a lot of time reading about the Civil War and Reconstruction, but in the seminal works of that era, there’s not a tremendous amount of stuff on what American Jews were doing at that time. And it was a pleasure to research that piece, because it was wonderful to learn about all the varied experiences of American Jews in this period in which other texts that I have read on Reconstruction simply didn’t go into. I’m still reading books about it.

JI: Do you think it’s something that you’ll write more about?

Serwer: Possibly. I mean, I think it’s a really fascinating subject, and part of why I wrote the essay was that I think that American Jewish liberal ethos is widely shared, but I don’t think it is widely known how far back it goes or where it comes from. I think we sort of generally think of it as emerging from the New Deal coalition and civil rights alliance. But it’s older than that, and it evolved organically out of historical conditions in the United States. I think it’s a fascinating history. We didn’t just get here in the 1930s, and so it was fun for me to learn more about that period.

JI: Definitely. Elected officials I interview often refer to the alliance forged between Jews and African Americans during the civil rights movement in the 1960s. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel is often invoked. But I guess what you’re saying is that’s not where that coalition originated.

Serwer: It’s an alliance of mutual interests. As I mentioned earlier, if you’re a religious or ethnic minority in a democracy, you have an interest in universal rights, regardless of background, being upheld. One thing I think is a problem is — I have gotten hate mail about this — where people present the civil rights alliance between Black Americans and Jews as sort of like a gift that Jews gave to Black people, and that’s really not the case. It was an alliance of mutual interests that had mutual benefits, and has somewhat eroded compared to its height, but which is still a crucial part of the progressive coalition for the same reasons.

JI: This is sort of a non sequitur, but I’m wondering if you’ve immersed yourself at all in the Jewish American literary canon, and if so which authors you like.

Serwer: Here’s the honest truth: I have not read a work of fiction in a very long time. I largely read for work, so almost everything I’m reading is a history book or a sociology book or something like that. I would love to regale you with my knowledge of Philip Roth or Bernard Malamud, but unfortunately, it’s been a long time since I’ve been able to sit down and enjoy fiction.

JI: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Serwer: I feel like regardless of how we feel about each other, the fates of Jews around the world are linked regardless of their level of observance or their political views. I don’t think that that obligates us to defend a particular political arrangement in the State of Israel. But I do think that, whether or not we like each other, history says that our fates are linked. And I think that’s important.