A lack of a ‘day-after plan’ and an unwillingness to address threats before they grew left Sharon’s 2005 promises unfulfilled. What has Israel learned since then?

AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti

A bulldozer breaks through the main gate as troops force their way into the Jewish settlement of Netzer Hazani, in the Gush Katif bloc of settlements, in the southern Gaza Strip, Thursday Aug. 18, 2005.

Twenty years ago this month, Israel dismantled 21 settlements in the Gaza Strip, forcing 8,000 Israelis to evacuate and demolishing their homes, in what was known as the disengagement. That process was met with mass protests on the streets and the splintering of the Likud party, whose leader, then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, initiated and oversaw the disengagement.

While Sharon did not promise peace as a result of the disengagement, the plan was presented as a move to make Israel more secure, while fewer soldiers would have to die protecting a small number of residents in the Gaza Strip. The prime minister and his supporters said that if even one rocket was shot from Gaza after the pull-out, Israel would respond militarily. They also promised that the disengagement would ensure that “this whole package called the Palestinian state, with all that it entails, [would be] removed indefinitely from our agenda … all with a presidential blessing and the ratification of both houses of Congress,” as Sharon’s senior advisor, Dov “Dubi” Weisglass, put it at the time.

Two decades later, Israel is fighting its longest war in Gaza, after the Oct. 7, 2023, massacres and attacks perpetrated by the Hamas terrorist organization that has controlled Gaza since 2006. In the interim years, Hamas and other Palestinian terrorist groups in Gaza shot hundreds and sometimes thousands of rockets at Israeli population centers each year, prompting five major Israeli military operations in Gaza.

As to Weisglass’ 2004 promise that international pressure to reach a two-state solution would be put in “formaldehyde,” Sharon’s political protege and the Israeli prime minister immediately following him, Ehud Olmert, offered the Palestinians a state in 2008. Last week, 11 countries announced their intention to recognize a Palestinian state.

Key figures from that period told Jewish Insider that the Israeli government’s failure to formulate a day-after plan for Gaza — a criticism that has been leveled at Jerusalem in the current war — is in part to blame for the unfulfilled promises of the disengagement.

Gilad Erdan, a former senior Israeli cabinet minister and ambassador to the U.S., was a freshman Likud lawmaker when the disengagement was announced, and became a leading figure in the party’s rebellion against Sharon, which then-Finance Minister Benjamin Netanyahu — who voted in favor of the disengagement plan in early key votes — joined at a later stage.

Erdan noted to JI that Sharon not only claimed the disengagement would improve Israel’s security, he said that “if Israel doesn’t take this step, there will be other diplomatic plans [that the world will] try to force on Israel, and this step will free us of pressure from the international community. It’s clear that it didn’t reduce pressure, it increased it.”

“What happened then, and is still the case now, is that Israel didn’t have an alternative plan on the table, whether for the coming few years or the short term,” Erdan said. “This is something to consider as a lesson of the disengagement.”

“I think a Palestinian state is now off of the agenda for many years … Something we can consider a lesson of the disengagement is that we should say no withdrawals, no unilateralism, no to a Palestinian state. I think those lessons were learned over the years at a great cost in blood,” said Gilad Erdan, who was a freshman Likud lawmaker when the disengagement was announced, and became a leading figure in the party’s rebellion against Sharon.

Israel now has “an opportunity to present a plan … that puts Israel’s security and our right to the land at the forefront, but we are not presenting any diplomatic plan for the world to discuss. Even if the international community doesn’t accept it — so what? What looks crazy today could look different in 20 years. It’s not like we’ll have peace with the Palestinians in five minutes,” the former ambassador stated.

Erdan said that the aftermath of the disengagement underscored for Israelis the danger of a potential Palestinian state.

“I think a Palestinian state is now off of the agenda for many years … Something we can consider a lesson of the disengagement is that we should say no withdrawals, no unilateralism, no to a Palestinian state. I think those lessons were learned over the years at a great cost in blood,” he said.

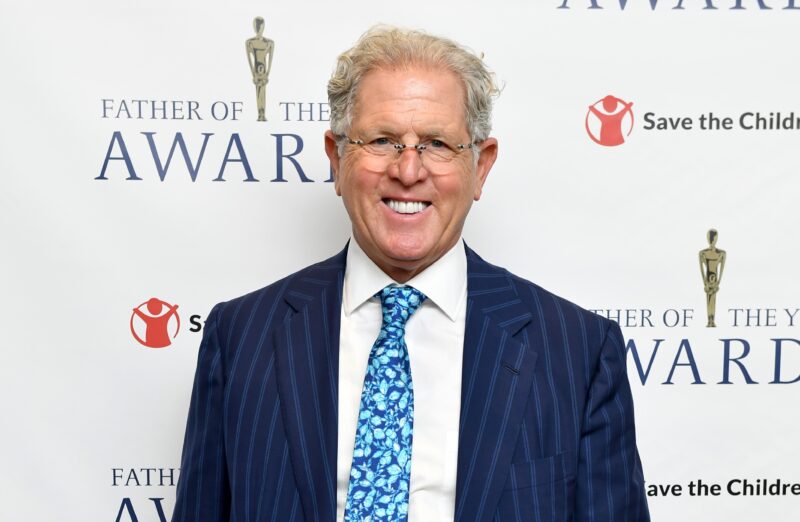

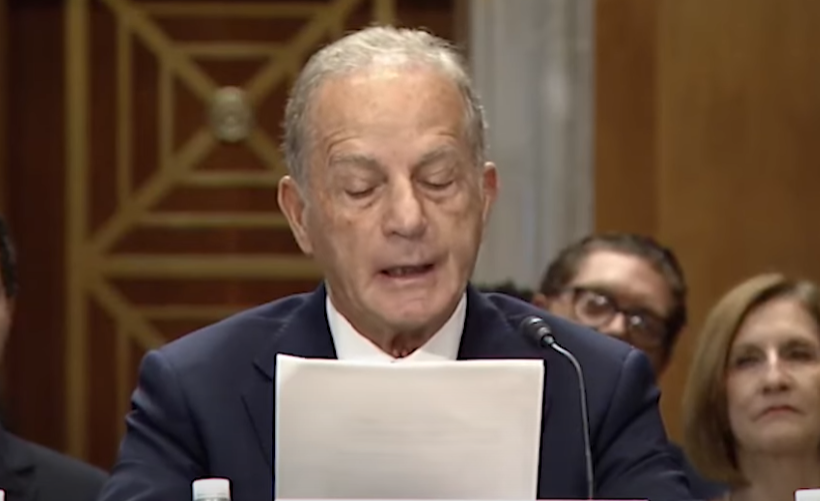

Elliott Abrams, who was deputy national security advisor to the George W. Bush administration at the time of the disengagement, told JI that Sharon did have a larger overarching idea behind the move, but subsequent prime ministers did not follow through with it.

“Sharon said at the time that Israel needs to establish its borders, and I think he would have done something … with the West Bank. Whatever the future of Israel is, it doesn’t include Gaza, which has no use economically and no significance religiously,” was the logic, Abrams said.

“Establish a border, build a wall, and maybe something will change in 100 years, but for now, try to have a border for Israel,” Abrams said. “It was a larger plan and then Sharon had his stroke” in December 2005, followed by another in January 2006 that left him in a vegetative state until his death in 2014.

“Sharon refused for domestic reasons to work with the Palestinian Authority at all on Gaza, because it would make it look like a reward,” following the years-long wave of Palestinian terrorism called the Second Intifada, Abrams recalled.

“Sharon wasn’t going to have anything to do with [the PA]; he was just going to leave Gaza,” Abrams said. “It’s a question whether it would have been possible to avoid a Hamas takeover in June 2006, followed by the complete collapse of the PA [in Gaza]. It’s a question worth asking. It is a fact that there was zero coordination.”

Though Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat died after Sharon announced the disengagement, the Israeli prime minister did not reconsider his plan in light of the election of new leader Mahmoud Abbas — who remains PA president 20 years later.

Abrams argued that international pressure was not a major contributing factor to the disengagement, noting that the plan was entirely Sharon’s and not something Bush sought for him to do.

Still, Abrams said that “international pressure to make concessions to the Palestinians is Israel’s predicament. That is simply a fact … I don’t think this is a problem that has a solution. I think it’s a condition.”

“Israelis have to decide when they’re going to say ‘drop dead,’ when they’re going to say politely ‘no, we can’t do that,’ when to take half measures and when they’re going to agree,” he added. “Those questions have not changed much. They get worse for a while sometimes, and then better and then worse again, depending on how successful Arab propaganda campaigns are and how unsuccessful Israel’s campaigns are. It also depends on how strong the support is from the U.S. in resisting the other pressure.”

Erdan similarly said that “Sharon sent Dubi Weisglass to convince [Bush], one of the most supportive presidents ever, to support the disengagement. Bush didn’t want to support it at first … there wasn’t such significant international pressure.”

Rather, Erdan, who was Sharon’s political advisor a decade before the disengagement, said the debate was more of a domestic Israeli one, after Sharon “changed 180 degrees from all of the ideas he had presented to us about security and ideology, Judea and Samaria,” the Biblical term for the West Bank.

The disengagement came after “Israel was under pressure from terrorism,” Erdan said.

“The disengagement was a terrible, historic mistake that inspired the Oct. 7 massacre,” Erdan argued. “It not only gave [Hamas] the opportunity to dig tunnels and arm itself, it gave them the motivation, the desire and the belief that they could do it. That the strong Israel, led by the decorated General Ariel Sharon, retreated unilaterally when facing terrorism strengthened the extremists in Palestinian society and led to the loss of deterrence we experienced two years ago.”

Erdan also argued that the disengagement did not reduce Israeli deaths, saying that the number of Israeli soldiers and civilians killed in attacks emanating from Gaza in 1967-2005, when Israel controlled the territory, was smaller than in the ensuing years 18 years before the latest war.

Abrams pointed out that Sharon and Olmert did not fulfill their promise of striking back if any attacks came from Gaza.

“The problem began very quickly,” Abrams recalled, “because Sharon in the first few months, and then after he had a stroke it was Olmert, never enforced their own statements about Gaza.”

Two Qassam rockets were shot from Gaza into Israel while the disengagement was still taking place, and another 33 during the remainder of that year. From 2005 to 2006, the number of rocket and mortar attacks from Gaza on Israel rose 42% to 1,777. Hamas also began building tunnels into Israel at that time.

Abrams recalled that when Sharon initiated the disengagement and presented it to Bush and then the public, Sharon argued that “if Israel got out of Gaza, there would be no excuse for any attack from Gaza on Israel, and if there were attacks, they would be met with the strongest, most forceful military reaction. It never happened.”

“Don’t let your enemies get into a position where they can do you great harm. That was learned, and that explains the attacks on Hezbollah and Iran. That is the right lesson. That is the lesson Israel did not seem to learn when it got out of Gaza,” said Elliott Abrams, who was deputy national security advisor to the George W. Bush administration at the time of the disengagement.

Israel at the time, he said, “had an opportunity to respond very strongly to Hamas right away, and it would have had considerable American and international support … It was an opportunity that was missed … by Sharon, Olmert and later [since 2009, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin] Netanyahu. It was a continuing problem.”

Abrams said that after the Oct. 7 attacks, Israel learned at least one lesson it had failed to internalize after the disengagement: “Don’t let your enemies get into a position where they can do you great harm. That was learned, and that explains the attacks on Hezbollah and Iran. That is the right lesson. That is the lesson Israel did not seem to learn when it got out of Gaza.”

“Israel is a democracy and the whole Jewish people debate about everything nonstop,” Erdan said, but “the lessons of the disengagement are growing over the years. It didn’t happen overnight.”

“In the early years after the disengagement, we realized the Palestinians had the ability and desire to launch missiles and rockets, so we can’t live in the delusion that [Gaza would be] the Singapore of the Middle East,” he said. “Only on Oct. 7 did many more people in Israel believe that not only unilateral but any withdrawal is bad. Israelis totally lost trust in the Palestinians and realized that Jewish settlements have a great and significant security value … We cannot only rely on technology and smart cameras; physical presence is essential … I think a lot of us woke up from our delusions on Oct. 7 that withdrawals will lead the Palestinians to reconcile with us.”

Still, Erdan said, “there are people who continue to claim that the price of staying in Gaza would be even higher, so I can’t say all the lessons were learned. With time, more are learned.”

“Having settlers in Gaza [would be] insane. It was a tremendous strain on the IDF. Do we really want to add that strain? It seems insane to me,” said Abrams.

It appears likely from Israeli leaders’ statements and positions in ceasefire negotiations that, at the end of the war, Israel will retain some of Gaza as a buffer zone between Israelis and Palestinians.

Beyond that, many on the Israeli right have called for Israel to retake part or all of Gaza. Some called for annexation as a military tactic to pressure Hamas, which was discussed in recent Israeli Security Cabinet meetings, and others have been calling from the beginning of the war to reverse the disengagement and for Israelis to be allowed to settle in Gaza again.

Abrams said that “having settlers in Gaza [would be] insane. It was a tremendous strain on the IDF. Do we really want to add that strain? It seems insane to me.”

Despite the lack of follow-through to reap the possible security benefits of the disengagement, Abrams said “Sharon was right.”

“First, we need to win the war,” Erdan said. “We are in a different situation today. Israel, unfortunately, already uprooted the [Israeli] towns and we are in a war with consequences for our future. I don’t think bringing the issue of settlements into it now contributes to our effort to win the campaign … We don’t have to give the international community more tools to make the matter of total victory in the war more complex … Israel should look at its interests and its priorities.”

“I personally do not believe that maintaining 7,000 [Israeli] settlers in the middle of 2 million hostile Arabs in Gaza, and using a substantial part of the IDF to protect them, was a sensible plan for Israel,” he said.

Abrams also took issue with the idea of annexing parts of Gaza to pressure Hamas: “It strikes me that that’s not going to move the remaining Hamas leadership living in tunnels in Gaza to agree to let the hostages out. They don’t seem to care about anything. It is truly a death cult … It doesn’t seem to me — putting aside the legality or illegality — that it would work.”

Erdan said that, in principle, he believes “Jews have the right to live anywhere in the Land of Israel, and a solution to a conflict must include the moral principle that every population can choose where to live and the other side must accept it.”

However, he said that Israeli resettlement of Gaza is “not the most urgent or central thing.”

“First, we need to win the war,” Erdan said. “We are in a different situation today. Israel, unfortunately, already uprooted the [Israeli] towns and we are in a war with consequences for our future. I don’t think bringing the issue of settlements into it now contributes to our effort to win the campaign … We don’t have to give the international community more tools to make the matter of total victory in the war more complex … Israel should look at its interests and its priorities.”

Abrams called the idea of maintaining a buffer zone “very sensible to protect Israelis in Israel.”

Erdan also favored Israel retaining a buffer zone in Gaza, because “even if Hamas isn’t there anymore, we don’t know who will be.”

“I don’t think the end lines of the war need to be the Sharon disengagement lines,” he said. “We don’t need to leave the Philadelphi Corridor [along the border with Egypt] and we don’t need the people of Gaza to return to live so close [to Israelis], almost up to my parents’ house in Ashkelon.”

A clear template is emerging of what the White House views as the ideal outcome here: deals, deals, deals — in classic Trump fashion

CHARLY TRIBALLEAU/AFP via Getty Images

Students are seen on the campus of Columbia University on April 14, 2025, in New York City.

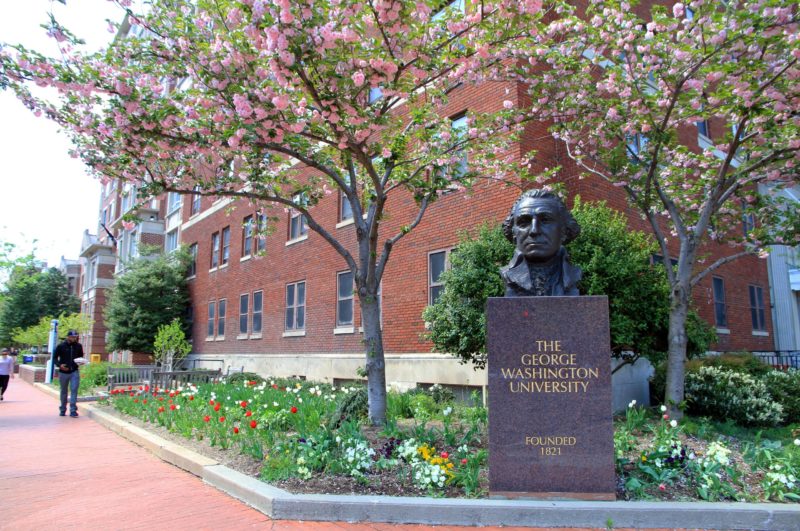

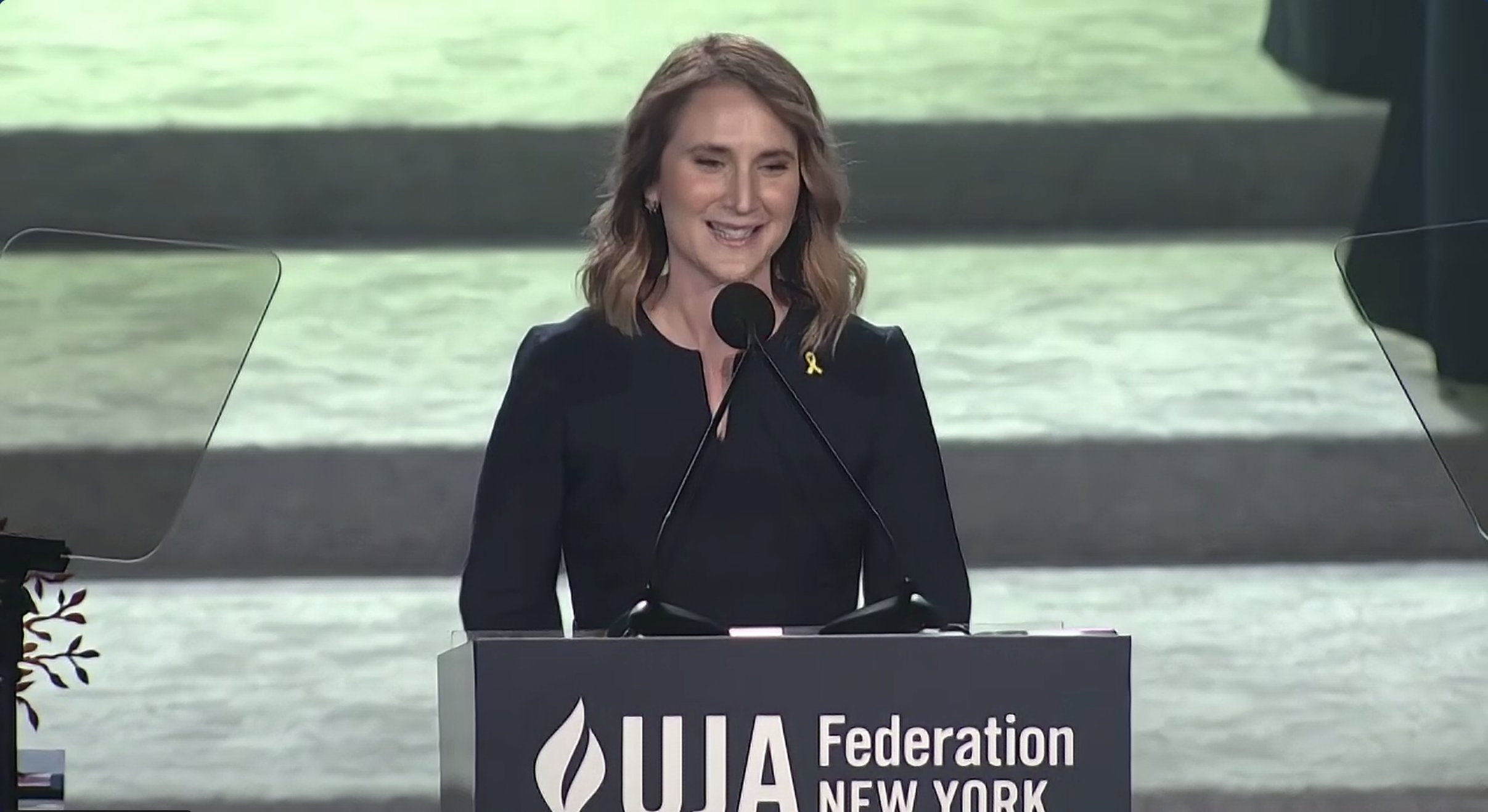

This week, the Trump administration demonstrated its endgame in its fight against campus antisemitism: hefty financial settlements.

Columbia University agreed to pay $221 million to the federal government to settle the administration’s civil rights investigation, and Brown University will pay $50 million to Rhode Island workforce development agencies to put a federal civil rights investigation to rest. Harvard is reportedly willing to spend up to $500 million on a settlement that is in the works. In return, frozen research grants to the tune of billions of dollars from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services will be reinstated.

What these early settlements have made clear is that antisemitism is only one small part of President Donald Trump’s fight against elite universities. The agreements offer a window into the other right-wing culture war issues driving his administration’s hard-charging negotiations with America’s top academic institutions. The lengthy documents also have the universities ceding to White House demands on diversity, equity and inclusion programs, race-based hiring standards, transgender issues and international students.

In its agreement with the White House, Columbia pledged to hire an administrator to “serve as a liaison to students concerning antisemitism issues,” and promised other sought-after changes, such as the hiring of new faculty members in the Israel and Jewish studies department and additional oversight of the school’s Middle East studies program.

But the propositions agreed to by Columbia go much further. The school pledged not to use racial preferences in admissions and promised to share admissions and hiring data with the federal government. The university also said it will allow any women who want it to have access to “single-sex housing” and “all-female sports, locker rooms and showering facilities,” a reference to Trump’s opposition to the inclusion of transgender women in women’s sports.

Brown’s settlement agreement is much more overt about the transgender issues — they’re the first issues addressed, above antisemitism. Below, Brown promised to take “significant, proactive, effective steps to combat antisemitism and ensure a campus environment free from harassment and discrimination.” Like Columbia, Brown will provide the federal government with admissions and hiring data.

A clear template is emerging of what the White House views as the ideal outcome here: deals, deals, deals — in classic Trump fashion. The most important question for Jewish students to consider as they return to campus in the next few weeks, though, is whether these deals will bring meaningful change for them. Some pro-Israel students at Harvard and Columbia told Jewish Insider this week that they’re worried the financial settlements may not do much to create real change.

Trump can now boast that he’s racked up wins with Columbia and Brown, and maybe even Harvard soon. Whether the deals lead to a calmer campus environment next year free of discrimination against Jewish students remains to be seen.

Plus, Leonardo DiCaprio's new Herzliya hotel

Kevin Carter/Getty Images

U.S. Capitol Building on January 18, 2025 in Washington, DC.

Good Wednesday morning.

In today’s Daily Kickoff, we talk to college students about the Trump administration’s efforts to reach settlements with schools over their handling of antisemitism on campus, and have the scoop on new legislation, introduced by Reps. Virginia Foxx and Josh Gottheimer, that would restrict federal funding to universities that engage in boycotts of Israel. We also report on the death of Blackstone executive and Jewish communal lay leader Wesley LePatner, who was killed in Monday’s shooting at the company’s headquarters, and look at stalled congressional efforts to address antisemitism. Also in today’s Daily Kickoff: Leonardo DiCaprio, Michel Issa, Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker and Penny Pritzker.

What We’re Watching

- The Senate is expected to vote today on two resolutions from Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) on blocking arms sales to Israel. More below.

- House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY) is slated to meet with Democrats in Texas today amid a broader debate over mid-decade redistricting, following President Donald Trump’s call for the Lone Star State to redraw the state’s congressional districts to give Republicans up to five additional seats.

What You Should Know

A QUICK WORD WITH JI’S MARC ROD

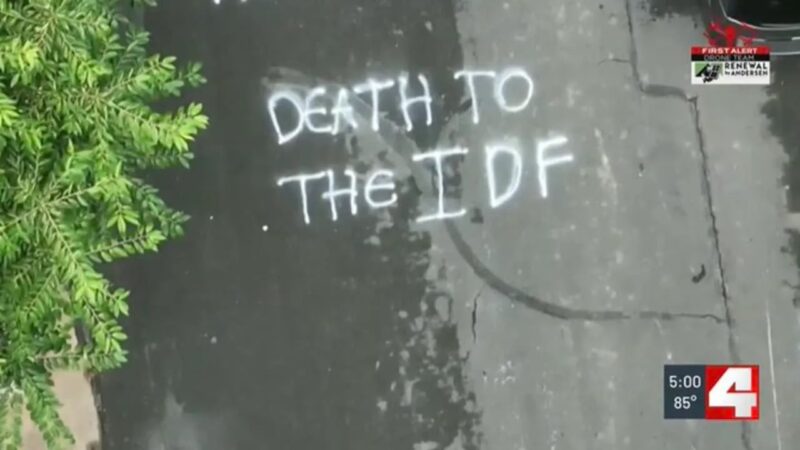

It’s been two months since the Capital Jewish Museum shooting in Washington and the Boulder, Colo., firebombing attack.

The two attacks prompted unified condemnation from lawmakers and calls from the Jewish community for Capitol Hill to take aggressive action against the escalating antisemitism crisis in the United States.

But as Congress heads into its August break, that initial momentum has produced little concrete action.

The House and Senate have passed resolutions condemning the attacks, but key legislation related to antisemitism remains stalled, even as lawmakers individually and in groups continue to press for action.

There are still no clear prospects for passage of the Antisemitism Awareness Act, a key element of congressional efforts to address antisemitism, after a contentious Senate committee hearing in April in which Democrats, joined by Republicans including Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY), voted to add amendments that most Republicans supporting the bill view as nonstarters. House leaders have made no public moves to advance the legislation.

And despite calls from Jewish groups for significant increases in nonprofit security funding to as much as $1 billion next year and a push from a bipartisan coalition of lawmakers for $500 million, the funding levels under consideration in the House are little different from those discussed in prior years.

Read more from JI senior congressional correspondent Marc Rod here.

MORE THAN MONEY

Pro-Israel students: University reforms must go beyond cash payments

When hundreds of pro-Israel college students from around the country gathered in Washington earlier this week for the Israel on Campus Coalition’s three-day annual national leadership summit, the rise of antisemitism on campuses sparked by the aftermath of the Oct. 7 terrorist attacks nearly two years ago was still a topic of conversation throughout panels and hallways. This year, however, some students, in conversations with Jewish Insider’s Haley Cohen, also said that antisemitism is lessening — though they offered mixed views about what is leading to the improved campus climate.

Students’ perspectives: Some attributed it to the Trump administration’s ongoing pressure campaign on universities to crack down on antisemitic behavior, which has included federal funding cuts from dozens of schools. Others said their campuses started to take a serious approach to antisemitism, before President Donald Trump was reelected, in the fall semester following the wave of anti-Israel encampments from the previous spring. But many student leaders from universities that have been targeted by the Trump administration — facing billions of dollars in slashed funds — said that if their school enters into negotiations to restore the money, they would like a deal to include structural reforms, unlike the one made last week between the federal government and Columbia University.

Suit settled: The University of California, Los Angeles settled a federal lawsuit this week with Jewish students who alleged that the university permitted antisemitic conduct during the spring 2024 anti-Israel encampments on the campus, according to a settlement agreement shared by the university on Tuesday, Jewish Insider’s Gabby Deutch reports.