Columbia’s Hillel director said that the university is on track for a large incoming class of Jewish freshmen next year

CHARLY TRIBALLEAU/AFP via Getty Images

Students are seen on the campus of Columbia University on April 14, 2025, in New York City.

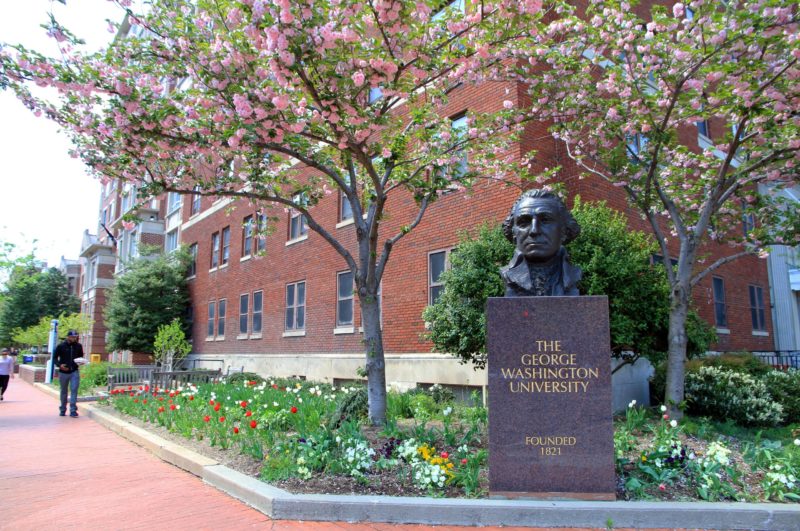

Earlier this year at a symposium in New York City, Jewish scholars gathered to analyze the recent surge of antisemitism on college campuses and debate whether Jewish students still belong at the country’s elite bastions of higher education.

“I certainly don’t think that we should abandon great citadels of learning or be chased out of them, although to be there takes fortitude that I don’t think should be asked of every student,” Rabbi David Wolpe, a former visiting scholar at Harvard University Divinity School, said during the event’s opening address. “So I’m going to give a selective answer: it depends who.”

Over the next two months, college freshmen will embark on new chapters at universities around the country. Many Jewish students have found appeal in other top schools, such as Vanderbilt in Nashville, Tenn., and Washington University in St. Louis, where administrators were quick to enforce university rules amid rising antisemitism in the aftermath of the Oct. 7, 2023, terrorist attacks, and therefore avoided much of the chaos that played out on other campuses.

But some Jewish students are still seeking admission to the country’s most prestigious schools.

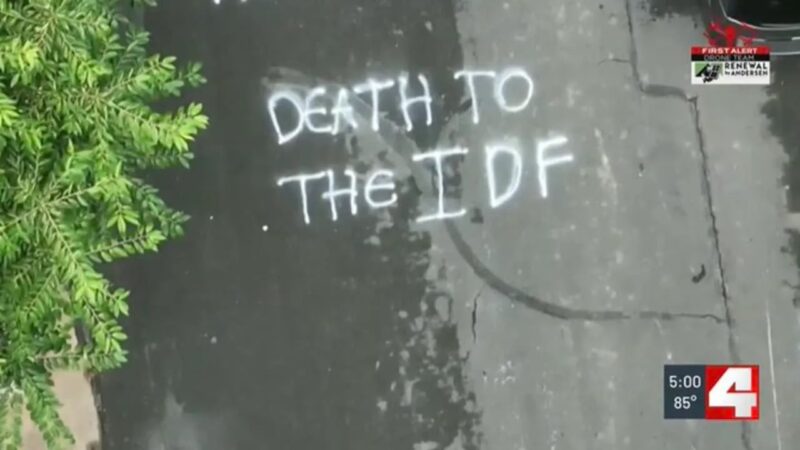

Who are these students making the choice to display the fortitude that Wolpe referenced by attending Columbia and Harvard —- two Ivy League campuses that have been beset by nearly two years of controversy over anti-Israel encampments and classroom disruptions, physical assaults of Jewish students and battles with the federal government, including potential loss of accreditation — over an alleged failure to address antisemitism?

Leah Kreisler, a recent graduate of Winston Churchill High School in Potomac, Md., decided in ninth grade that she wanted to attend Columbia. Kreisler plans to enroll in Columbia’s dual-degree program with the Jewish Theological Seminary and will begin next year, following a gap year in Israel.

Recent events have only reinforced Kreisler’s dream of attending the storied institution. “Columbia has always had a politically charged environment and I honestly think that fits a part of who I am,” she told Jewish Insider. “I like having those kinds of discussions and engaging with people I disagree with. That spirit drew me to the school.”

She’s also hopeful that by the time she arrives at Columbia for the 2026-27 school year, “things will get figured out.” The university is in talks with the federal government to restore the institution’s federal funding, which was slashed in March due to the antisemitic demonstrations that have roiled the campus since Oct. 7.

Still, Kreisler admitted she’s “a little bit scared” to face antisemitism, which she hasn’t directly encountered in her tight-knit D.C. suburb with a sizable Jewish community. “There will probably be people in the streets doing antisemitic things,” she said, noting that she often gets “weird looks from Jewish members of the community” when she shares her plans to attend Columbia.

Laura Hosid runs a private business in Potomac guiding high school students through the college admissions process. She works with many students like Kreisler who are “often willing to overlook [antisemitism] at schools like Harvard and Columbia, if they can get in,” Hosid, who is Jewish, told JI.

“At slightly less selective schools, though, it’s more of a factor,” she said. “Students are willing to look away if there’s too much anti-Israel stuff.”

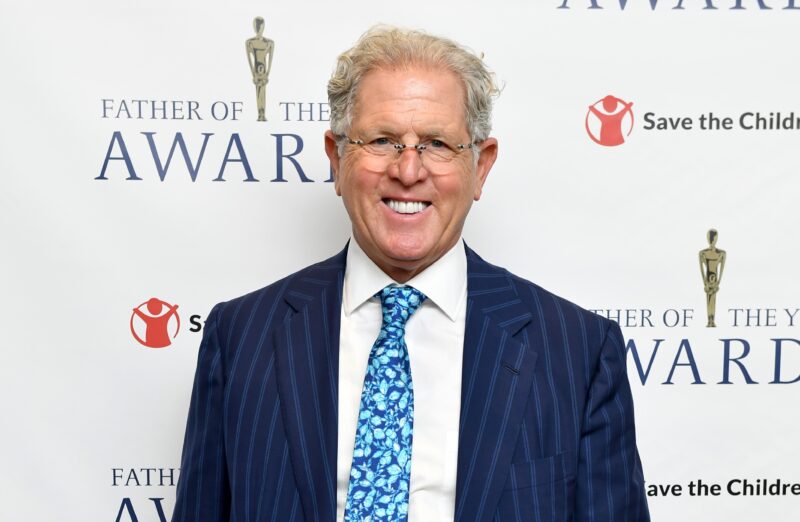

“Jewish life at Columbia is Dickens-esque: the best of times and the worst of times,” said a Jewish Columbia alum who requested to remain anonymous. “There are real challenges, but at the same time, you can go to Columbia Hillel, the Kraft Center for Jewish Life, and access the most interesting people in the world. Bob Kraft shows up for events,” he said, referencing the billionaire owner of the New England Patriots for whom the center is named.

“I’m certainly not discouraging students if they are interested in schools like Columbia and Harvard,” Hosid continued. “I’m just making sure that they are well aware of what’s going on there and how it compares to what the climate is like at other schools.”

A Jewish Columbia alum who requested to remain anonymous told JI that he still sees his alma mater as “an amazing New York City school with an incredible alumni network.” So he was supportive when his daughter, an incoming Columbia freshman, committed to the university.

“Jewish life at Columbia is Dickens-esque: the best of times and the worst of times,” he said. “There are real challenges, but at the same time, you can go to Columbia Hillel, the Kraft Center for Jewish Life, and access the most interesting people in the world. Bob Kraft shows up for events,” he said, referencing the billionaire owner of the New England Patriots for whom the center is named.

In 1967, Columbia’s student body was 40% Jewish, according to a Jewish Telegraphic Agency report at the time. But even as Jewish enrollment at Columbia has declined since then, it still has one of the highest percentages of Jewish undergraduates in the Ivy League, at an estimated 22%. “The numbers for this year’s incoming class are quite strong,” Brian Cohen, executive director of Columbia Hillel, told JI.

Cohen said that the center’s “top priority is to make sure that every Jewish student feels seen and supported and part of a vibrant Jewish community from the moment they arrive at Columbia University.”

“Everything we hear anecdotally is that the number of applications of Jewishly involved students to Harvard were stable — if not increased — from last year to this year,” said Rabbi Jason Rubenstein, the director of Harvard Hillel.

That’s been Hillel’s goal for years — even before antisemitism reached record highs on campus. But Cohen noted that for the past two academic years, “everything is ramped up.”

“We want to make sure that when we meet students and families face-to-face they already have some idea of who we are and the relationship isn’t starting from square one,” he said, outlining two priorities. “One is that students understand that they are entering into this thriving, diverse Jewish community on campus. [The second is] that, should any problems arise during their time at Columbia, they have trusted resources to go to that are easily accessible and can help support them in navigating the various university processes.”

Rabbi Jason Rubenstein, the director of Harvard Hillel, is similarly spending the summer preparing for a new class of Jewish students. He’s hearing less concern around antisemitism from incoming students and their parents compared to last year. “I think that’s a combination of all of us adjusting our baselines and knowing what we’re getting into, and that last year was calmer on campus than the year before.”

Like Columbia, Harvard has had billions of dollars in federal grants and contracts frozen by the Trump administration. The university filed suit against the government in April, claiming that the cuts violate the First Amendment. A 300-page antisemitism report released by the university in April described “severe problems” that Harvard’s Jewish students have faced in the classroom, on social media and through campus protests.

“Everything we hear anecdotally is that the number of applications of Jewishly involved students to Harvard were stable — if not increased — from last year to this year,” Rubenstein said. Ramaz, a Modern Orthodox Jewish day school in Manhattan, for instance, admitted five students to Harvard the past admissions cycle, with four planning to attend. “That’s the highest in living memory,” Rubenstein said.

One of the Ramaz graduates starting at Harvard this fall is Stella Hiltzik, who grew up hearing “incredible stories” from her mother’s time on the Boston campus. “But it wasn’t until I visited Harvard last year that I decided that was the place I wanted to be,” Hiltzik, whose major is undecided, told JI. She was drawn to Harvard “even despite all of the crazy things happening on campus” after seeing “how supportive, warm and comforting Jewish life on campus is — especially the Chabad. It feels like a sense of home,” Hiltzik said.

“Despite everything going on, when I say I’m going to Harvard, most people are proud of me and supportive,” Hiltzik continued. “But there are some people who ask me, ‘What are you thinking?’ For me, it’s honestly a cool conversation to have, because I get to tell them how I’m excited to be a Jewish voice on campus during these hard times.”

“Despite everything that has happened at Columbia,” Leah Kreisler, a recent graduate of Winston Churchill High School in Potomac, Md., said, “I don’t think that the solution to antisemitism is to remove ourselves from these institutions. That’s been my mentality throughout the college [application] process.”

“Jewish students are not being dissuaded,” Rubenstein said. “Which is a great thing because some people are chanting ‘Zionists are not welcome here’ and the one thing they most want is Jewish students to not come here.”

Students like Hiltzik and Kreisler offer a quiet rebuke to the billionaire alums of the Ivies who have begun to withhold their considerable donations. One Israeli venture capitalist went as far as to try to lure Jewish students attending Ivy League schools to transfer to universities in Israel.

“Despite everything that has happened at Columbia,” Kreisler said, “I don’t think that the solution to antisemitism is to remove ourselves from these institutions. That’s been my mentality throughout the college [application] process.”

“People shouldn’t be afraid to go to any of these schools,” echoed Hiltzik. “At the end of the day, you’re going to get a good education and you’re going to show everyone how cool it is to be a proud Jew. I feel, in a sense, that this is my version of fighting for my people.”