A former French culture minister, Azoulay is the first Jewish leader of the controversial U.N. agency

Li Yang/China News Service/VCG via Getty Images

Audrey Azoulay, director-general of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), delivers a speech during the opening ceremony of the 47th session of the World Heritage Committee on July 7, 2025 in Paris, France.

When Audrey Azoulay was elected director-general of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization in 2017, many U.N. watchers — including some of its staunchest critics — were pleasantly surprised that UNESCO’s members had selected a Jew to lead the organization for the first time since it was founded in 1946.

The timing of Azoulay’s come-from-behind two-vote victory over a Qatari competitor came with a tinge of irony: Just one day earlier, the United States and Israel had each announced their intention to withdraw from the body, citing its persistent anti-Israel slant and “extreme politicization.”

The organization tasked with preserving cultural heritage sites around the world has for decades faced accusations of political bias. President Ronald Reagan first pulled the U.S. out of the body in 1984 over allegations of anti-Western, pro-Soviet sentiment.

When UNESCO became the first U.N. body to vote to admit the “State of Palestine” as a full voting member in 2011, the U.S. cut funding to the organization. In 2016, UNESCO passed a controversial resolution about the Temple Mount in Jerusalem that ignored Jewish ties to the holy site. A year later, Israel and the U.S. cut ties entirely.

All of that was before Azoulay took the helm of UNESCO. Now her leadership is in the spotlight, after the Trump administration said last week that it would again depart the body, following President Joe Biden’s decision to reenter UNESCO in 2023. “UNESCO works to advance divisive social and cultural causes,” State Department spokesperson Tammy Bruce said this month, arguing that the organization perpetuates “a globalist ideological agenda for international development at odds with our America First foreign policy.”

But Azoulay, a former French culture minister who comes from an illustrious Moroccan Jewish family, said in a statement last week that “the situation has changed profoundly” since the U.S. departed UNESCO in 2018. “These claims also contradict the reality of UNESCO’s efforts, particularly in the field of Holocaust education and the fight against antisemitism,” she said. UNESCO declined to make Azoulay available for an interview, but a spokesperson noted that “the level of tension” within the body on Middle East issues “has been reduced, which is a unique situation in the U.N. system today.”

Her lobbying is unlikely to impact the Trump administration. But even without the U.S. as a member, UNESCO remains an important global organization with lofty goals: “to create solutions to some of the greatest challenges of our time, and foster a world of greater equality and peace.” Azoulay has bought into that mission, with the added challenge of trying to make the organization less politically toxic in a polarized world.

“She really came into office intent on changing UNESCO’s public image and internal work,” Deborah Lipstadt, the former U.S. special envoy to monitor and combat antisemitism, told Jewish Insider this week. She has worked with Azoulay on antisemitism-related programming since 2018. “I think she recognized the flaws that had been prevalent before, and I think she was really trying to turn things around, and she deserves great credit for that.”

Azoulay grew up in France, but her family hails from Essaouira, a seaside Moroccan city that was once majority Jewish, though she rarely speaks about her family’s story. Her father, André Azoulay, spent the first two decades of his career climbing the ranks at Paribas Bank in Paris, before he returned to Morocco in 1990 to serve as an advisor to King Hassan II. Now, he is a senior advisor to King Mohammed VI, and his influence is rumored to be expansive.

“She is a really remarkable person, to have come from this Moroccan Jewish background, to become so French that she’s a minister in the French government, and then to achieve this position in UNESCO,” said Jason Guberman, executive director of the American Sephardi Federation. Whatever people want to say about UNESCO, I think you have to judge her by what she has done.”

“Azoulay is the kingdom’s all-purpose fixer, a man who gets stuff done thanks to an endless list of high-profile contacts who wouldn’t dare to ignore his calls,” Tablet Magazine wrote in a 2018 profile of the elder Azoulay.

When he inaugurated a structure called Beit Dakira — “House of Memory” — in Essaouira in 2020, to preserve the city’s Jewish heritage, his daughter attended the event on behalf of UNESCO. She has worked in several French government agencies, and before being named culture minister in 2016, Azoulay was an advisor to French President Francois Hollande.

“She is a really remarkable person, to have come from this Moroccan Jewish background, to become so French that she’s a minister in the French government, and then to achieve this position in UNESCO,” said Jason Guberman, executive director of the American Sephardi Federation, who attended the Essaouira event in 2020. He worked with Azoulay on a 2021 World Philosophy Event celebrating Muslim and Jewish poetry. “Whatever people want to say about UNESCO, I think you have to judge her by what she has done,” said Guberman.

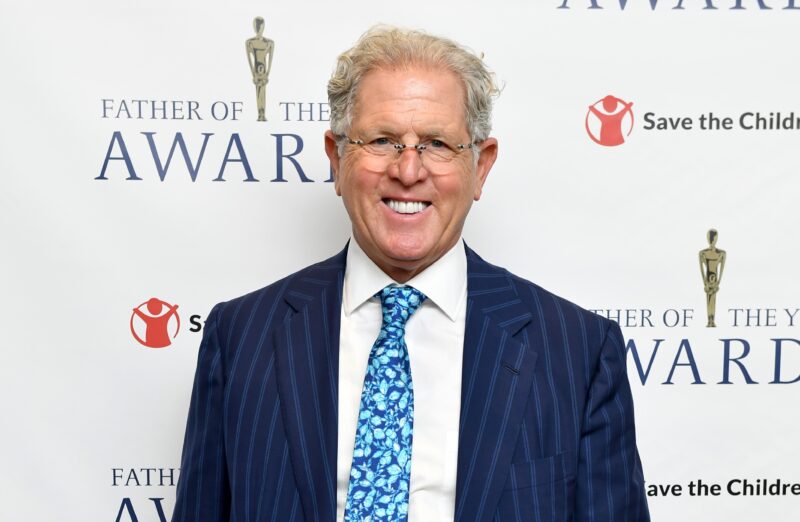

UNESCO has worked closely with the World Jewish Congress in recent years, particularly on programming related to Holocaust education. Its president, Ronald Lauder, wrote in a 2018 op-ed that UNESCO’s history of dozens of resolutions condemning Israel “makes a mockery of the U.N.” Azoulay, he wrote, has been able to move the organization forward — to a point.

“She was able to accomplish some things diplomatically with Israel that hadn’t been done before. She got the president to come to Holocaust Remembrance Day, and that was the first time that ever happened,” said David Killion, who served as U.S. ambassador to UNESCO in the Obama administration.

“Audrey Azoulay, the new head of UNESCO, is making great strides correcting this and we applaud her for what she’s doing. But after decades of bad behavior at UNESCO, its reputation cannot be cleansed overnight. Especially when this virus of antisemitism still runs throughout the entire body of the U.N.,” Lauder wrote.

Azoulay reportedly urged Israel not to exit the organization in 2018, arguing at the time that UNESCO had made progress in fighting bias. Israel still left. But she pulled off a strategic victory in 2022.

“She was able to accomplish some things diplomatically with Israel that hadn’t been done before. She got the president to come to Holocaust Remembrance Day, and that was the first time that ever happened,” said David Killion, who served as U.S. ambassador to UNESCO in the Obama administration.

In Israeli President Isaac Herzog’s virtual remarks at a UNESCO Holocaust remembrance event in 2022, he directly praised Azoulay. They were unexpected words from a country that had previously offered sharp criticism of the organization.

“UNESCO has the tools with which to inform the younger generation about what happened and teach them what must never be allowed to happen again,” Herzog said. “I wish to recognize UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay for her strong leadership.”

Azoulay said in a speech soon after the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas terror attacks that UNESCO “was born out of the ashes of the Holocaust and the Second World War,” which is why, she said, fighting Holocaust denial remains a key priority of the organization.

That work has been done in partnership with the World Jewish Congress, American Jewish Committee, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and, for a period, the Biden administration. Former Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff met with Azoulay at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris last year and pledged that the U.S. would contribute $2.2 million to a UNESCO program to teach about the Holocaust and genocide.

But the agency’s commitment to fighting antisemitism has been tested since Oct. 7.

Speaking to a global gathering of antisemitism special envoys two weeks after the attacks, Azoulay said the Hamas terrorists operated “in the same modus operandi as the pogroms.” After the “massacres” that day, Azoulay added, “We have seen a new wave of antisemitism, regrettably with all the hallmarks of our time.”

Since then, though, UNESCO has mostly directed its ire at Israel’s actions in Gaza. Critics have noted, for instance, that UNESCO has warned of damage to cultural heritage sites in Gaza and Lebanon, while not expressing the same degree of concern about sites in Israel. At a recent meeting of UNESCO’s executive board, the agency voted to approve several measures calling out Israel’s actions in Gaza, the West Bank and the Golan Heights.

“That kind of stuff remains, and it’s really bigger than her, because I think that’s the point with any U.N. [agency]. The system is so geared against Israel,” said Anne Herzberg, legal advisor at NGO Monitor, a research institute that is critical of the U.N. system. “I do think she’s well-intentioned, and I do think she has made efforts to try to depoliticize the agency. I don’t want to cast aspersions on her at all, but I do think the problem is, you’re operating in a system that’s almost impossible to change.”