Sarah Hurwitz said she hopes her second book, ‘As a Jew,’ resonates with progressive Jews who have distanced themselves from Zionism

Courtesy

Sarah Hurwitz

Growing up at a Reform temple in suburban Boston, Sarah Hurwitz learned that Judaism is just “four holidays, two texts and a few universalistic values.”

When she left home, she largely eschewed all Jewish observance for two decades, she reflected in a recent interview with Jewish Insider. In that time, she got two degrees at Harvard and reached the pinnacle of Washington success, serving as a senior speechwriter, first to President Barack Obama and then to First Lady Michelle Obama. If she engaged with Judaism at all, it was with a light touch — she was merely a “cultural Jew,” as she usually called herself.

“I just didn’t realize there was Jewish culture. I just meant, ‘Oh, I’m anxious and kind of funny,’” Hurwitz told JI last month.

Approaching a midlife crisis, Hurwitz found her way to an intro to Judaism class at a Washington synagogue nearly a decade ago. She embarked on a journey of learning Jewish traditions and studying Jewish texts that sparked her first book, the 2019 Here All Along, a joyful and accessible primer to Judaism.

“Its thesis was, ‘Isn’t Judaism amazing?’ Not a lot of Jews are going to disagree with that thesis,” Hurwitz said.

She is doing something different with her new book, As A Jew: Reclaiming Our Story From Those Who Blame, Shame, and Try to Erase Us, which was published this week.

“This is definitely a book with an argument. It is definitely edgier than my first book,” Hurwitz said.

That’s because in As A Jew, Hurwitz is grappling with a question that struck at the core of who she is, or at least who she was until a decade ago. Why, she asks, was she always qualifying her Judaism? She was always a “cultural Jew,” an “ethnic Jew,” a “social justice Jew,” she writes. Hurwitz was never simply a Jew, one word, proud, head tall.

In her new book, as she tackles the millennia of antisemitism that led her to unwittingly minimize her own identity, she is asking questions that others who similarly distort or diminish their Jewish identity may not want to face.

“I was really trying to make others comfortable with me, right? I didn’t want them to think I was one of those really Jew-y Jews, which … why would that be bad, again?” Hurwitz said. “Why did social justice have to be my Judaism? Why couldn’t Judaism be my Judaism?”

This doesn’t mean Hurwitz is criticizing people who engage with Judaism through a social justice lens, or through culture, or any other avenue besides religious observance. Her own personal Jewish learning journey has not made her an Orthodox Jew. The argument she’s making is that Jews should engage with Judaism … well, Jewishly — by learning what Jewish texts have to say about social justice, rather than taking some universal values like “care for the vulnerable” and calling that your Judaism.

“Social justice is also a gorgeous way to be a Jew when you actually know what Judaism says about social justice,” said Hurwitz. “When I was this kind of contentless Jew, I don’t really know what I was doing. I was often just articulating my own views and opinions and kind of attributing them to Judaism.”

She begins with a basic question: The Holocaust happened because the Nazis hated the Jews. But why did they hate the Jews? OK, the Jews were the scapegoat after World War I. But why the Jews? That unanswered question makes it hard for anyone to identify modern-day antisemitism, Hurwitz argues.

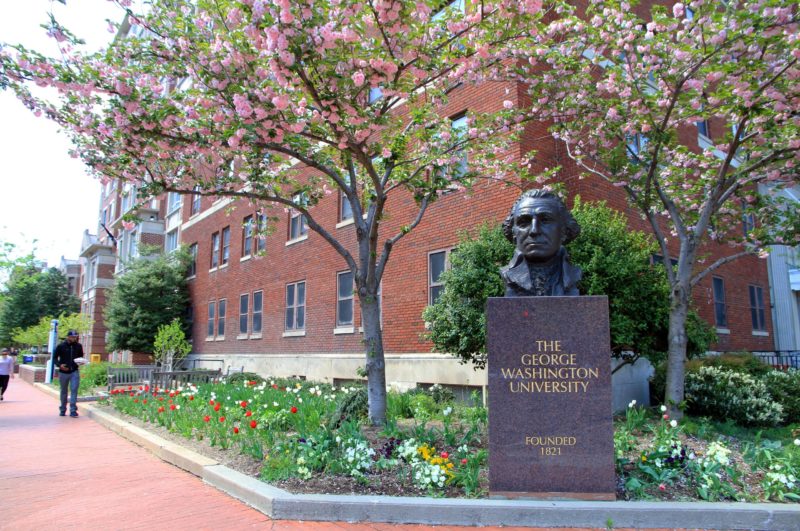

“These poor kids, it’s very confusing, because they’ve gotten Holocaust education, and they’re like, ‘That’s antisemitism education,’” said Hurwitz. “And then you get to campus and there are no Nazis, and you’re like, ‘What is this?’”

To answer that, she goes back thousands of years. The book examines Judaism in the context of the historical movements that have tried to crush it, or at least confine it: early Christianity, the Crusades, the Spanish Inquisition, the Enlightenment, the Holocaust. Not each of these eras sought to eliminate Judaism, but each one presented a particular idea of the good kind of Jew.

Throughout history, some Jews always tried to adapt to the mores of the day and disavow essential parts of Judaism in order to fit in. The only problem, writes Hurwitz, is it didn’t work. You can be Jewish, but not too Jewish. Like when modernity swept across Western Europe in the 19th century, and Jews could suddenly become citizens of France and Germany — so long as they placed their country’s identity above their Jewish identity.

“This book was very much my journey to stripping away all those layers of internalized antisemitism, anti-Judaism, all of that internalized shame from so many years of persecution, and just saying, ‘You know what, no, I’m a Jew,’” said Hurwitz.

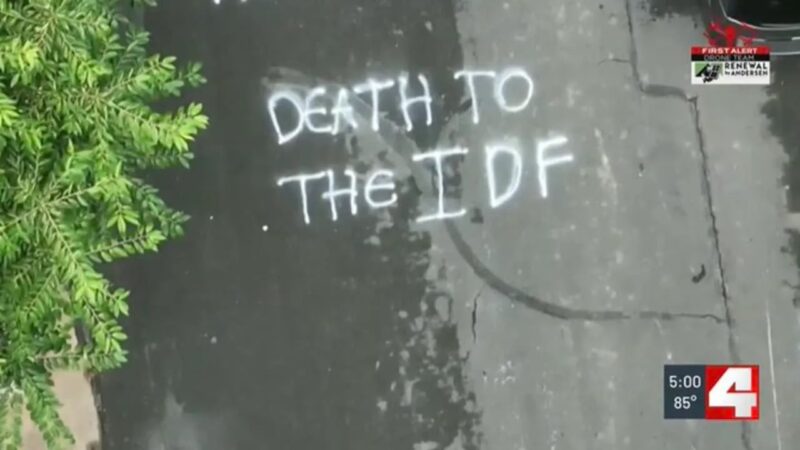

Hurwitz pitched this book before the Oct. 7 Hamas attacks that sparked a wave of global antisemitism. But she says the events of the last two years have only furthered her argument that Jews throughout history have felt the need to separate from parts of their community to earn the approval of the rest of society.

“Oct. 7 did not change the overall argument at all. It unfortunately, in many ways, gave this devastating, heartbreaking, new evidence from the argument,” Hurwitz said.

Hurwitz hopes to reach a broad audience. But she spent a decade and a half enmeshed in Democratic politics professionally, and she particularly hopes to can reach Jews on the left who have distanced themselves from Zionism partly as a condition of their belonging in progressive spaces.

“I am hoping that I can speak particularly to Jews who maybe have identified as Democrats, who are a little bit more on the left, and I can tell them why I am a Zionist. I can tell them why I think it is so important that Israel exists,” Hurwitz said. “I can make that argument, and I’m hoping that it will be credible coming from me, in a way that maybe it wouldn’t from others.”