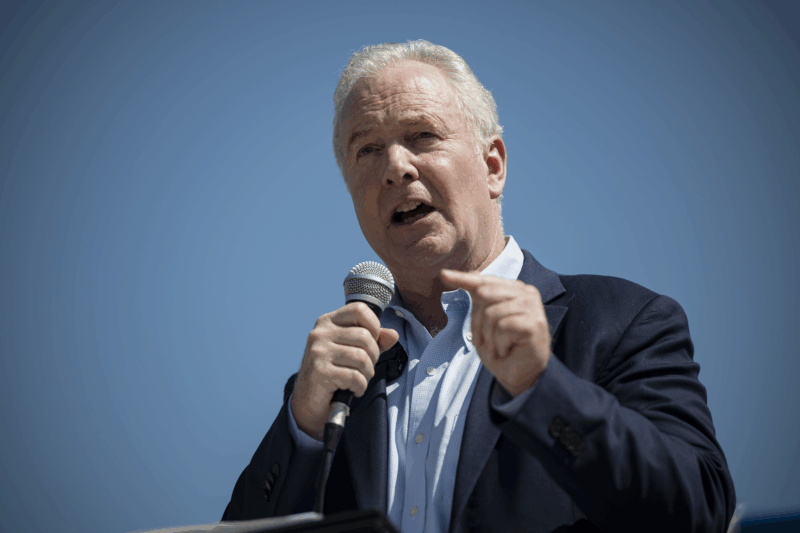

The NYTimes reporter who traded in the sports beat to cover ‘identity wars’

Michael Powell: 'I’m always interested in things that kind of cut against what we think of as "the narrative"'

YouTube

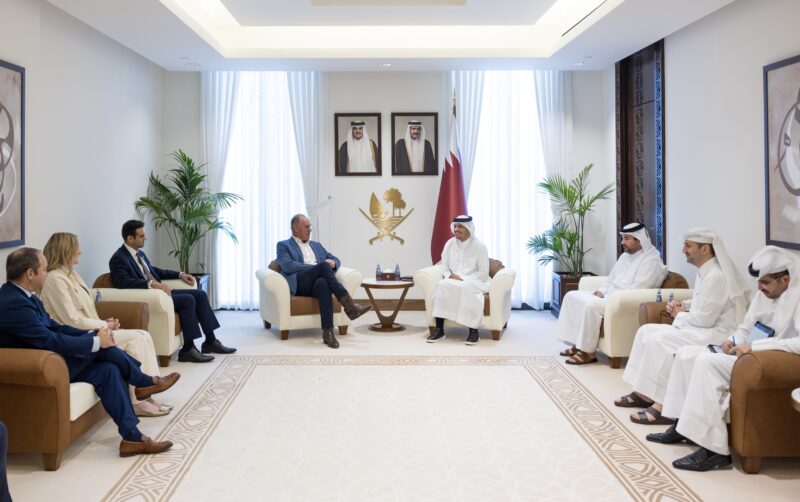

Michael Powell

There was a moment, just after the coronavirus was beginning to spread unabated throughout the United States, when New York Times reporter Michael Powell began to think he had made a grievous mistake.

Powell recently dropped his sports column and migrated to the news desk, where he is now writing about free speech and identity issues — a brand new beat for the Times. But as the disease became an “all-consuming horror,” he recalled, Powell noticed that some pontificators were declaring that the so-called “identity wars” had been rendered irrelevant by the pandemic.

“There was a feeling of, like, I’m going to write about somebody being canceled on a campus that isn’t even open?” Powell mused in a phone interview with Jewish Insider from his home in the Ditmas Park section of Brooklyn on Friday afternoon.

Of course, Powell now feels that his coverage area is secure as mass protests against police brutality have swept the nation, bringing his focus into the center of the national dialogue. “I don’t think I have to worry that it’s going to go away anywhere anytime soon,” he said.

His first piece on the beat zeroes in on a red-hot topic: the Trump administration’s overhaul — via Education Secretary Betsy DeVos — of campus sexual misconduct regulations. The article describes how DeVos’s proposal has won unexpected support from some feminist legal scholars who argued that the previous rules flouted due process.

“There’s a really, to me, interesting, intellectually valid, emotionally intriguing argument to be made for the DeVos standards, and that’s what drove me to those three female law professors,” said the 62-year-old reporter, who has done stints at New York Newsday and The New York Observer, among other publications.

Powell previously wrote the Times’s “Gotham” column, for the Metropolitan section, before moving to sports in 2014.

The journalist, who has worked at the Times since 2007, has always enjoyed taking on controversial stories. “I like trying to explain positions and to get inside thinking in a way that isn’t necessarily my own,” he told JI, characterizing his new beat as “the third rail of our culture and politics.”

“If you’re going to try to engage with the culture and you’re going to try to engage with people’s thinking, particularly at a time like this, where everyone is at loggerheads and there’s so little nuance,” he said, “it’s just inevitable that you’re going to encounter anger.”

Powell only decided to make the shift to that third rail four months ago, he said, when he told his editor, Carolyn Ryan, that he was getting “restless” covering sports. Though he enjoyed his column, he said he knew he would return to news at some point during his tenure at the Times, and now seemed like the right time to do it.

“There’s sometimes a tendency to figure out, ‘Oh, if you’re X — gender, race, whatever — then you have a predictable set of views that follow from that,” he said. “And that always strikes me as stultifying and sad.”

“Right now, I think, in a lot of writing, there’s a strong kind of Black identity emphasis,” he said. “And that’s all interesting and very often very powerful. There’s also a world of thought out there — this goes for every single racial, ethnic group — that is different than that. I mean, there are Black left writers who take the view that class is more important than race. There are, obviously, guys like Glenn Loury, who’s a very conservative, very smart, Black economist up at Brown.”

The new beat comes at a somewhat tense moment for the Times, as staff members have butted heads with management over the paper’s decision to publish an opinion piece by Sen. Tom Cotton (R-AR) advocating for military force to quell protests against systemic racism.

Days after the piece was published, Times opinion editor James Bennet, who said he had not read the essay before it was published, resigned from the paper.

Powell, for his part, said he understood the concern that some of his colleagues felt when the article ran. “I very much get the passion on all sides of this,” he told JI judiciously.

Still, he said he wasn’t bothered that the op-ed ran because it was written by a powerful Republican politician whose views may have reflected conversations going on in the White House and Senate at the time.

“And I guess my take,” he said, laughing nervously, “which isn’t to argue it’s the take, but my take is I can’t see where it isn’t good to know that.”

“One of the challenges the Times faces is that it doesn’t want to get pigeonholed as just a paper for liberals or for the left, and that’s a goal I support,” Powell told JI. “That would never, in my eyes, involve going easy, ever, on any topic.”

“We have an incredibly sophisticated readership, probably the most sophisticated general newspaper readership in the world, and we have an incredibly sophisticated staff, and we should be very well capable of hearing and wrestling with views that many of us might find objectionable,” said Powell, noting that he has friends at the paper who objected to the Cotton piece and those who were unoffended by it. “That’s kind of part of what we do.”

But Powell can’t very well be expected to write about his own workplace. (That’s media columnist Ben Smith’s job.) So, as he plans future stories, he said he is looking forward to writing about such hot-button issues as Title IX, transgender athletes and other topics touching on race and class.

“In this particular end of the forest,” he said, “there’s more subjects to hunt and look at then there is time in the day.”

Powell told JI he would like to interview the novelist Margaret Atwood, who has “been really interesting and counterintuitive on things” like cultural appropriation. “I’m always interested in things that kind of cut against what we think of as ‘the narrative,’” he said.

And Powell acknowledged that a number of the topics he covers will require he wade into perilous territory.

“You’re going to take a lot of flack at some point,” he said, “but to some extent, if you don’t like that, then you should get out of journalism.”