Norman Podhoretz remembered as visionary of neoconservative thought

The longtime Commentary editor’s passionate defense of Israel helped shape the Republican Party of the time

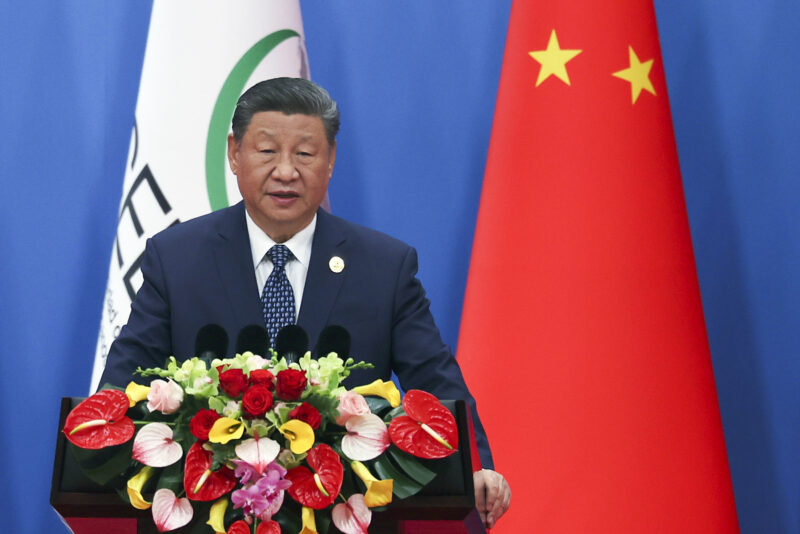

(Photo by David Howells/Corbis via Getty Images)

American neoconservative theorist and writer Norman Podhoretz at home in New York City.

Norman Podhoretz, the pugnacious editor and neoconservative pioneer who died on Tuesday at the age of 95, charted a protean trajectory through American politics and intellectual discourse, rising to prominence as a leading champion of a muscular foreign policy vision conjoined with a fierce support for Israel that influenced such presidents as Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush.

Despite his early political conversion from staunch liberal to conservative trailblazer, Podhoretz — the always-ambitious son of a Yiddish-speaking milkman from Eastern Europe who was born in Brownsville, Brooklyn — remained consistent in his commitment to defending Israel as well as promoting the Jewish ideals that guided his social and professional ascent.

During his 35-year tenure helming Commentary— from 1960 to 1995 — he established the periodical as a lightning rod of disputatious ideas that helped drive the conservative movement, while at the same time building his reputation as an estimable thinker in Jewish American debate of the mid-20th century.

Under his editorial stewardship, Podhoretz transformed the magazine — then published by the American Jewish Committee — into a pro-Israel force that significantly shaped American foreign policy in the Middle East while helping steer the GOP to a more instinctive embrace of the Jewish state as a key ally.

“The neoconservatives played a pivotal role in providing the intellectual firepower for the case for Israel,” Jacob Heilbrunn, the author of a book about the movement Podhoretz founded, They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons, told Jewish Insider in an interview on Wednesday. “They did that not only by arguing that Israel was a vital outpost in opposing the spread of communism in the Middle East, but also in forging and defending the rise of the evangelicals who supported Israel.”

Absent Podhoretz and his ideological comrades including Irving Kristol, another neoconservative leader, “I don’t think that you would have had the intellectual justification for defending Israel inside the GOP,” Heilbrunn said, noting that the party had previously been “hostile to Israel.”

Podhoretz, who wrote a dozen books including his score-settling debut memoir, Making It, published in 1967, was an erstwhile liberal who abandoned the left-wing New York intellectual milieu that nurtured his rise and turned to neoconservatism in the 1960s, after growing disillusioned with a counterculture he viewed as increasingly hostile to Israel following the Six Day War.

“Podhoretz was the founder of neoconservatism,” Joshua Muravchik, an author and like-minded foreign policy expert, told JI, noting that the “role is sometimes ascribed to Irving Kristol. In truth, there were two strands.”

Kristol, he argued, “led a group of thinkers who reckoned with the limits of social engineering and the welfare state” — while Podhoretz “led a deeper project, the rediscovery or reassertion of the moral greatness of America, of democracy and of Western civilization.”

“This made him not only a great American patriot but a great Jewish patriot,” he said, “because Israel is a precious, against-all-odds outpost of Western civilization and because the roots of American civic culture and Western civilization are found in the Hebrew bible.”

In publishing major articles by the likes of Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Jeane Kirkpatrick as well as Norman Mailer and Philip Roth, Podhoretz “set a high standard for Jewish intellectual periodicals” while also playing “a role in opening up the Jewish community to more conservative views that had not previously been admitted,” said Jonathan Sarna, a professor of American Jewish history at Brandeis University.

“Even those who didn’t agree with him I think respected his standard,” Sarna, who published his first article in Commentary in his mid-20s, told JI in an interview. “I’m sure I’m not the only one who feels indebted to Norman.”

Mark Gerson, an author and businessman who interviewed Podhoretz while working on his 1997 book, The Neoconservative Vision, called the late editor “a towering intellectual” and a “great man of ideas who made Commentary, when he took it over, one of the best magazines or publications ever.”

“It was always interesting, always intellectually serious, always rigorous, always challenging,” he said. Podhoretz, who was otherwise recognized as an astute if often acid-penned literary critic, “had a unique ability to come up with the most interesting ideas, to tell the most visceral truths and to recruit some people who became defining the writers of his generation,” Gerson told JI.

The magazine is now edited by Podhoretz’s son, John, who wrote in a tribute on Tuesday that his father’s “knowledge extended beyond literature to Jewish history, Jewish thinking, Jewish faith, and the Hebrew Bible.”

“Norman believed that words matter, and arguments matter, and his leadership of Commentary was a 30-year effort at putting forward the best arguments in defense of America, Israel, the West and the Jews,” said Elliott Abrams, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and Podhoretz’s stepson-in-law. “He looked for the best writers and champions of this cause, from Moynihan and Kirkpatrick to dozens of young voices, and he engaged them in this noble cause.”

“There was no magic formula beyond logic, language and unwavering moral commitment,” Abrams told JI.

Podhoretz, of course, had many critics on the left and right — including among some former writers. Robert Alter, the renowned biblical translator who frequently contributed to Commentary, said he had “mixed thoughts about Norman.”

“Early in his career, he was admirable in attracting promising young writers,” he told JI on Wednesday. “His staunch defense of Israel, as the American left moved toward anti-Israel positions after 1967, was politically valuable.”

But while Podhoretz had “made Commentary the central journal in American intellectual life” during the 1960s, his politics had, by the end of the decade, “hardened into a rather rigid neoconservatism,” he added. “The eventual result was that Commentary became a kind of sectarian publication with a much smaller readership.”

In recent years, the movement Podhoretz led has also faced backlash from isolationist and America First conservatives who have pejoratively invoked the term “neoconservative” as representative of the sort of hawkish interventionism that helped lead the U.S. into war in Iraq and other quagmires across the Middle East.

Though his movement was usurped by President Donald Trump, Podhoretz — unlike other fellow neoconservatives — backed his campaign in 2016, citing concerns about Hillary Clinton’s support for the Iran nuclear agreement which he viewed as disastrous. In a characteristically cutting explanation, Podhoretz said at the time that he skeptically viewed Trump as “Pat Buchanan without the antisemitism,” underscoring the extent to which his attachment to Israel fueled his political thinking.

But even as the ideals that Podhoretz had long championed have largely “been steamrollered now by Trump,” said Heilbrunn, the scrappy editor and public intellectual “will be there in the conservative pantheon” and “played a key role in reshaping the Republican Party.”

“And who knows, neoconservatism is a protean movement,” Heilbrunn speculated. “It can always make a comeback.”