In debut book, Yardena Schwartz links past and present horrors in Hebron and the Gaza envelope

“It I felt as if I was living the pages of testimony that I had spent years reading and researching for this book,” journalist and author Yardena Schwartz told JI

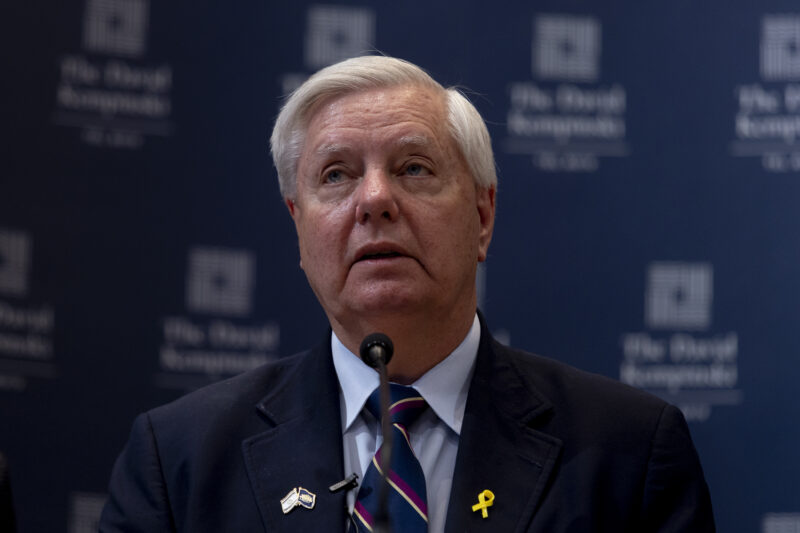

Courtesy

Yardena Schwartz

Journalist Yardena Schwartz had nearly finished the manuscript for her first book, focused on the 1929 Hebron pogrom in which dozens of Jews were killed and a community was destroyed, on the morning of Oct. 7, 2023.

As reports emerged in the following days of the atrocities that took place across southern Israeli communities and the Nova music festival, “it I felt as if I was living the pages of testimony that I had spent years reading and researching for this book,” Schwartz told Jewish Insider in a recent interview about her book, Ghosts of a Holy War: The 1929 Massacre in Palestine That Ignited the Arab-Israeli Conflict. “It felt like they were coming to life. I felt like it was exactly what happened in Hebron occurring today. And it was so chilling.”

Schwartz intended to write a book based on the letters and diaries written by a young Jewish American man named David Shainberg, who, inspired by his faith, moved to Hebron to study at a renowned yeshiva, when he was killed on Aug. 24, 1929. A niece of Shainberg’s found the writings in the family’s home in Tennessee, where they had been collecting dust, and reached out to author Yossi Klein Halevi, who in turn suggested Schwartz take on the challenge of giving life to the story of a young man whose life was cut short.

What Schwartz found was extensive, if scattered, documentation of the 1929 pogrom and its aftermath. There was no English-language compendium focused on the massacre that killed nearly 70 Jews and left more than 100 wounded.

“I felt that if I’m going to write the first book in English that really goes into detail about the massacre and its causes and its aftermath,” Schwartz, a former NBC News journalist, told JI, “I need to do justice to those victims by detailing in as much detail as I can what what happened to them, not only for future generations to know about it, but so that it can’t be denied.”

It was an unintentionally prescient concern that was validated last year, when denials about the extent of Hamas’ atrocities on Oct. 7 began to emerge in the days and weeks that followed. It was through that lens that Schwartz finished the final chapters of her book, which took on a new direction in the wake of last year’s attacks, to weave together the stories, separated by a century, of Jewish pain and resilience.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Jewish Insider: You had not been planning to write a book, certainly on Hebron, and this story was just dropped on you. What was your first reaction when finding out about David and the letters?

Yardena Schwartz: So I had always dreamed of writing a book, but it always seemed like this fantasy. I had this hope in the back of my mind that something would just find me, but I never expected it would be this. I never expected it would be about Hebron, especially since I had only been to Hebron once before I was introduced to this family. I woke up on New Year’s Day in 2019 with an email from Yossi Klein Halevi, who was not yet my mentor, but would become my mentor. And it was very simple. [He said], ‘I met this family who found this box of letters in their attic. It’s a treasure trove of history, of Hebron and the massacre, and I think it would make a great book, but I can’t do it. Are you interested?’

JI: What was it like piecing together the history of Hebron?

YS: So much of the research involved going to Hebron itself and interviewing Israelis, settlers and Palestinians who live both on the Israeli side of Hebron and on the Palestinian side of Hebron. I spent hundreds of hours interviewing Palestinians and Israelis about life today in Hebron to understand, and also their stories of their families in Hebron, and then for the history part of it, hundreds of hours reading archival materials, reading books that were written by people who’d lived in Hebron at the time that David lived there, survivors of the massacre, eyewitness testimony from the massacre by survivors and victims, by British officials who testified before the Shaw Commission, which came to Palestine after the riots to investigate. I read the testimony of the British police chief who was in charge of Hebron, testimonies of people who stood before the trials that the British conducted after the riots, newspaper articles that were published in 1928 and 1929 about the lead-up to the massacre, [which] was actually a whole year of propaganda that was disseminated by the Grand Mufti, and not just propaganda, but also this campaign of trying to limit Jewish access to the Western Wall. So there was a lot of newspaper coverage of that, not just in publications like the Palestine Post, which would eventually become the Jerusalem Post, but also The New York Times, JTA, The Times of London. There was a lot of both primary source material from people who were living in Palestine at the time, and also newspaper reports from the time.

JI: What most surprised you over the course of your research and your interviews?

YS: Wow, there were so many moments in researching this book that I was just flabbergasted by how shocking some of these details were, yet so little known. First, the massacre itself, just the atrocities were so brutal and so hauntingly similar to the atrocities that were committed on Oct. 7. And yet I was shocked that such a massive event that made such an impact on the trajectory of Palestine, of Zionism, of the State of Israel, of the Jewish community in what was then Palestine — it had such a lasting impact on not just that land itself, but also the entire region, and yet we still know so little about it.

The fact that this conflict has been going on for a century, and yet so little has changed over the course of a century. One hundred years ago, when the Jews were massacred in what was then Palestine, that massacre was followed by widespread denials by Arab leaders and by the Arab populace. At the same time, the perpetrators of the massacre were celebrated as heroes, and at the same time, their attacks were blamed on their Jewish victims.

If that wasn’t mind boggling enough, after Oct. 7, I saw these same patterns emerge. When I was researching and writing about this massacre, I never once, not even once, for a second, imagined that something even remotely similar to that massacre could happen again on that scale — and that it happened again on a scale far greater than what happened in 1929 and was also being met by denials. And not just denials, but in 1929 the denials came from the Arab leadership. The victim-blaming was from the Arab leadership. And today, not only are those denials and victim-blaming coming from the Arab leaders, but from academia, from media, every respected avenue of society is denying that those atrocities were carried out, and simultaneously blaming the victims.

JI: Where were you in the book process on Oct. 7?

YS: I was pretty close to finishing the book. I was about three-quarters through, maybe two-thirds of the way. I was supposed to submit my manuscript in April of 2024, so I still had some time to finish the manuscript. After Oct. 7, I was pretty incapacitated. I would try to continue writing these chapters as I imagined them looking and I just couldn’t. It just didn’t make sense anymore. The plan I had for how these chapters would look, it just didn’t make sense anymore. The book before Oct. 7 was very much focused on Hebron itself and how it went from being this beacon of coexistence to the antithesis of peaceful coexistence that it is today, through the lens of this massacre and all the forces that it accelerated or galvanized. So when I sat down and tried to write based on that theme, the words weren’t flowing. So I took a break for a few months to go back to reporting because I had taken a long break from reporting to write this book, and I was reporting primarily on the hostage crisis and interviewing hostage family members, families who had lost loved ones and been in the kibbutzim on Oct. 7. And when I came back to writing the book, I understood that I had to just throw away entire chapters.

JI: I want to flip it, you just talked about the way that Oct. 7 influenced the book. When you wrote about the Hebron massacre, you got into the details. How did having just researched and written so deeply about the atrocities of 1929 affect how you experienced Oct. 7 and the weeks after?

YS: Of the chapters that I had finished writing, and I had considered final, the massacre chapter was the most polished. I had worked on that most. I had finished it long before Oct.7, and I was pretty far into writing the rest of the book when Oct. 7 happened. So when I woke up on Oct. 7, it was the most disorienting feeling, because I felt as if I was living the pages of testimony that I had spent years reading and researching for this book. It felt like they were coming to life. I felt like it was exactly what happened in Hebron occurring today. And it was so chilling. And I think the way that I wrote about the massacre of 1929, in this very detailed way, giving life to the people who were killed. I didn’t just mention the numbers of people killed, I really wanted to bring them to life and give them justice, give their lives justice by naming them, describing who they were before the massacre and what their lives were like before they were killed. And I think that helped inform the way I wrote about the atrocities on Oct. 7. I named the people. I went into great detail, how they experienced it, and what that day was like for them, from morning to night and both before the massacre and after, in both cases, both in 1929 and with the massacre of Oct. 7.

I did that because, in the case of 1929, when I was writing this chapter long before Oct. 7, I understood that so few people know about this massacre, including myself. And that’s because there has been so little written about it in English. In Hebrew and in Israeli culture, everybody knows about the massacre of 1929 and I think people know not just that it happened, but the scale and the brutality. And that’s because in Hebrew, there are so many books written. So I felt that if I’m going to write the first book in English that really goes into detail the massacre and its causes and its aftermath, I need to do justice to those victims by detailing in as much detail as I can what what happened to them, not only for future generations to know about it, but so that it can’t be denied. And that’s also why I sourced the book so extensively.

JI: It’s interesting that you bring up that there’s not an English-language accounting of what happened. But it seems like with your book and with Oren Kessler’s book last year, there has been kind of this renewed focus on how Israel’s pre-state years have shaped so much of what we see today. And so I wonder what other stories there are to be told.

YS: My hope is that this book, as well as Oren Kessler’s fantastic book, that this will help inform what has increasingly become this really disinformed conversation around the conflict. And I think a lot of it is because people’s attention spans are so short, and it’s very easy to just look at this conflict through the lens of what’s happening now. And if you look at what’s happening now, it’s a very simple story, there’s a right and a wrong, and when you look at just what’s happening today, it’s easy to come to conclusions, like maybe Ta-Nehisi Coates would like people to come to but you can’t erase the history of this conflict. It will never be solved either, if that history is ignored and if the context of this conflict is just brushed aside. Maybe it’ll be easier for you to make sense of it, or wrap your head around it, but it’s only going to push peace further into the distance if the true sources of this conflict are ignored, and the true sources of this conflict are very clear if you look at the history going back the last century.

JI: You had written very early on in the book, when you were talking about the propaganda that preceded the massacre, that the “truth had become irrelevant.” And as I read that sentence, I thought we could just as easily say this today.

YS: It’s the exact same playbook. And of all the things that have not changed over the last century, one very important thing has changed, and not for the better. If you look at the international media’s coverage of the riots of 1929, you see that the media was playing the role it needed to play, which was doing reporting and giving to readers a story that shows them what is the truth. That is the essential role of journalism: to get to the truth and give the truth to your readers. And today we look at the coverage of a massacre that was even larger, even worse, and yet that role is nowhere to be found. One hundred years after that massacre, we see the media not portraying these denials and victim-blaming for what they are, as lies, or these absurd claims of, for instance, the Al-Ahli Hospital, just parroting claims by terrorist organizations that are clearly false and and not portraying them as false or as lies, but giving them the same weight as truthful claims, or claims of the IDF, or of Israeli officials or of Israeli citizens. It’s all just portrayed as this, ‘He said, she said,’ rather than, ‘This is what happened.’ Why even publish these absurd claims? Because you’re giving truth to it when you publish it, and the media is leaving readers to decide what’s true and what’s false. Whereas, in 1929, 100 years ago, you think that over 100 years, the media would improve in its role — It’s only failed the true test of journalism.

I often wonder if the massacre of 1929 were to happen today, when Arab leadership put out those statements saying, ‘No atrocities were carried out in Hebron,’ the media in 1929 portrayed those denials as outright lies. The media in 1929 covered these wild claims that the atrocities were carried out by Jewish students, [but] they portrayed them as wild lies. It was very clear that these were lies, and yet today, I’d imagine that publications like The New York Times would publish those denials and victim-blaming as if they were true. And that is, I think, one of the greatest drivers of this conflict — the media’s failure to call out disinformation for what it is and to even recognize disinformation for what it is. I think a lot of journalists perpetuating these lies don’t even know their lies.

JI: In the book, when you go back to Hebron on a media tour and you’re in a meeting with the mayor, you observe that you are probably the only foreign journalist in that room who knew that he took part in the 1980 attack [in which six Jewish men, including two Americans, were killed in Hebron walking home from Shabbat services]. I’ve seen so many foreign correspondents who parachute in with no understanding about this conflict. I think it underscores the issue that we’re seeing with not just the big stuff, like the hospital, but the everyday reporting.

YS: I’m so glad you brought that up, because that’s such a great example of why knowing this history and having this contextual framework when you approach reporting on this conflict, why it’s so important. Because imagine I’m sitting in that room with this mayor who I have no idea perpetrated a deadly terror attack on civilians in 1980, the same terror attack that led the Israeli government to actually approve the renewal of the Jewish community in Hebron. And I’m sitting in this room and I hear him say, ‘The creation of this new Jewish residential building is a terrorist attack on the Palestinian people, and it will lead to the whole Palestinian population being evicted from this area,’ and I just take him at face value, I just publish what he says. But I don’t do that because I know that he actually served time for a terrorist attack. So it’s mind-boggling for him to call a building a terrorist attack. And I know that his claims of mass Palestinian evictions from this area are absolutely false, because I know that this building is being built on lands where no one lives, it’s an abandoned space. And I also know that when he tells this room full of journalists that already there’s been this mass exile of Palestinians from the Israeli side of Hebron, I know also that that’s false, because I know that the difference in the Palestinian population on that side of Hebron has decreased by maybe 1,000 over the course of 30 years, and that also, the Jewish population of that same area has remained stagnant since 1929. The people sitting in that room are just going to publish what he says without checking the facts. I don’t know if I blame journalists, because I think the reason there was this ability to discern fact from falsehood was because journalists had more time to report and to speak to people and to get the historical context into their stories. And I think today, journalists are churning out multiple stories a day. I’m not excusing their laziness or their failure to understand that you need the historical context and reporting on such an important issue like this, but I think that has a lot to do with it. There is no time, I think, for many journalists to do this historical research before publishing their stories, and so they just get lazy and report what they’re told without checking it themselves to make sure it’s accurate.

JI: What can we take from 1929 and from 2023? When you think about the Jewish future and in Israel, what lessons are there to take as you look to how the Jewish community reinvents and grows itself and rebuilds itself in the wake of such a catastrophe?

YS: Well, I think that my greatest lesson in writing this book, and I hope it’s clear to anyone who reads it, is that peace has always been possible, and I think that the only reason why we haven’t had peace for the last century is because leaders — corrupt leaders who benefit from disinformation and propaganda — have hijacked the future of Israelis and Palestinians to their own benefit and to the detriment of all of us, and too many innocent Palestinian lives and Israeli lives have suffered as a result of corrupt Arab leaders perpetuating the same propaganda and the same lies and weaponizing Islam and weaponizing Al Aqsa. I think that reversing that and ending that disinformation and that propaganda is the only way we will have peace. And I think that we see that going back to 1929, through today, moderate peace-seeking voices among the Arabs of Palestine and among Palestinians today have been silenced by intimidation or by assassination. People who are calling for peace today among Palestinians are labeled as collaborators, and if not silenced by intimidation, they’re killed. And I think that the only way we will have peace is if peace-seeking, moderate voices among Palestinians and the Arab public no longer have to fear for their lives, and those people need to be empowered, and those people need to be able to speak out without fearing for their lives. And if the people who seek peace continue to fail to see that and continue to allow Arab leaders to perpetuate the same disinformation and lies that have led to so much death, so much needless death and destruction, then we’re just going to be destined for another century of massacres. The people who are protesting against the war and for Palestinian lives, and in defense of Palestinian lives, they need to understand that Hamas and Hezbollah are only going to bring more destruction and more death and more wars, and if they really want peace, as all of us do, then it’s these peace-seeking voices within the Palestinian people who need to be elevated and empowered, not groups like Hamas and Hezbollah.