GOP budget cut plans raise concerns about defense spending levels

Republicans are aiming to balance the budget over 10 years, with the specific goal of rolling back spending to 2022 levels

Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images

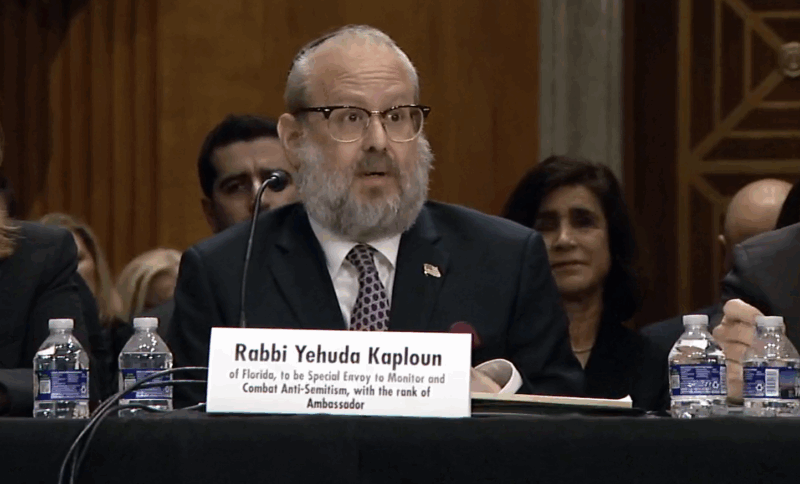

Reps. Chip Roy (R-TX), Mary Miller (R-IL), Scott Perry (R-PA), Byron Donalds (R-FL) and others talk to reporters in Statuary Hall after switching their support for Speaker of the House to Republican leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) during the fourth day of elections at the U.S. Capitol Building on January 06, 2023, in Washington, D.C.

Among the raft of concessions made by House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) to a group of conservative House members in exchange for their support last week was a commitment to working toward a balanced federal budget over 10 years — including potentially punishing cuts to spending as Congress plans the 2024 federal budget. The plans raised early concerns about potential cuts to defense spending.

The exact details of the deal, including how firm or binding the commitment to budget cuts and spending targets may be, remain unclear. The budget and spending-related agreements are not part of the publicly released rules package that the House will vote on Monday. But, according to Republicans who spoke to reporters on Friday, the House will seek to cap discretionary spending at 2022 levels, potentially setting up cuts to defense and non-defense programs supported by the Jewish community.

The deal generated initial headlines indicating that defense spending would be scaled back by $75 billion — reversing last year’s increase, which raised spending to $858 billion in 2023 from $782 billion in 2022 — but lawmakers said that no specific cuts had yet been negotiated, other than the overall topline figure. McCarthy negotiators also repeatedly referred to the topline goal on Friday as “aspirational.”

“There’s not a specific number cap [for any category of spending] other than the aspirational goal for domestic discretionary at the FY22 levels,” Rep. French Hill (R-AR) told reporters on Friday. He said it would be up to the Budget Committee to help determine, through a standard amendment process — rather than the backdoor negotiations that have helped shape recent spending bills — how the spending cuts would be distributed.

Rep. Chip Roy (R-TX), a lead negotiator for the group of House members who objected to McCarthy’s bid through multiple rounds of voting last week, likewise emphasized that no specific cuts had been determined.

“Anytime in this town that anybody talks about checking spending… they immediately start talking about what it’s cutting or not cutting,” Roy said. “That is not a part of this conversation [currently] with respect to what is specifically being cut or not cut.”

But Rep. Ralph Norman (R-SC), who had also opposed McCarthy’s bid before ultimately backing the California Republican, emphasized that defense spending cuts are on the table.

“Everything will be looked at… You can’t have a balanced budget unless you start cutting,” Norman said. “The dollars that go to defense — we’ve got to look at every dollar there as well as every other agency.”

He added that he sees defense spending as “probably the most important agency we’ve got.”

Rep. Tom Cole (R-OK), the incoming chairman of the powerful House Rules Committee, said that “the debate is over when you cut, how do you keep the essential things like defense appropriately funded. We’re pretty good at working those issues.”

But at least some colleagues are expressing early concerns about what the planned cuts could mean for defense funding. Many Republicans and some Democrats, particularly defense hawks, have spent the past two years pushing successfully for defense spending levels above those requested by the Biden administration. For 2023, the Biden administration requested $813.3 billion for defense.

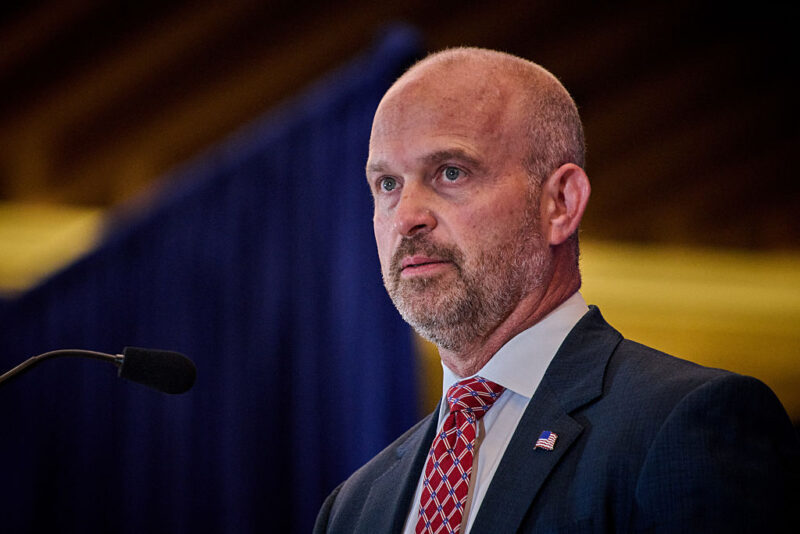

“My concern, though, is in order to keep defense numbers, we’d have to have a 20 to 25% cut in non-defense,” Rep. Michael Waltz (R-FL) said. “Numbers are getting thrown around, $90 billion, $75 billion — there is nothing in our rules that are written that we have to have that kind of a cut. But I worry if you just look at the reality of how these appropriations deals work between defense and non-defense historically, that it could [happen].”

Waltz noted that Congress had enacted similar spending cuts in the past, pointing to the deep budget cuts it implemented around 2011.

“Our military needs to deter and compete with China, Russia, Iran, North Korea and global terrorism,” Waltz said. “We need to balance our budget, absolutely, I 100% agree with that. But we’re not going to do it on the backs of our troops.”

Rep. Don Bacon (R-NE) told reporters he believes that defense funding needs to continue to increase at least the level of inflation, saying that doing otherwise would function as a de-facto cut to defense spending.

“I don’t think it’s realistic,” to go back to 2022 levels, Bacon said. “There may be some desires for 2021 levels of funding, but in the defense [budget], I don’t believe it will happen. We’ve got China, we’ve got Russia, we’ve got Iran. Our military junior enlisted [personnel] are on food stamps when they’re married. That’s unacceptable.”

Base-level U.S. military aid to Israel — $3.8 billion annually, drawing from both the State and Foreign Operations and Defense budgets — is promised by an ongoing Memorandum of Understanding, which Congress codified into law, and backed by most members of Congress. It is unlikely to see major changes, although some conservatives in both the House and Senate oppose foreign aid. Rep. Thomas Massie (R-KY), a libertarian who opposes all foreign aid including to Israel, is reportedly being considered for a position on the Rules Committee.

But a range of other programs supported by the Jewish community falls under the non-defense bucket that could be targeted for cuts. Jewish community leaders who spoke to Jewish Insider last month before the specific budget plans emerged remained cautiously optimistic that funding for the Nonprofit Security Grant Program, which provides security funding to religious institutions and nonprofits, would survive budget cuts expected under House Republicans.

“Without being overly optimistic, this has been a perennially popular program on both sides of the aisle,” Elana Broitman, the Jewish Federations of North America’s senior vice president for public affairs, said in December. “I’m more optimistic about this program than maybe I will be about others.”

Nathan Diament, the executive director of the Orthodox Union Advocacy Center, offered a similar outlook in early December, before 2023 funding for the program had been finalized.

“We did have early in the program the two budget cycles in which it got cut from $25 million down to $10 million because everything in the government was cut across the board. I think that’s extremely unlikely to happen again,” Diament said, referring to sequestration — mass spending cuts across the government — in the early 2010s, mandated by the Budget Control Act of 2011 to which Waltz alluded.

The bipartisan 2023 National Defense Authorization Act passed in December supported funding the NSGP at $360 million each year for the next five years, although the final 2023 budget only included $305 million for the program.

House Republicans have committed to passing 12 separate appropriations bills this year for each different category of spending, each with an open amendment process on the House floor — meaning any member can introduce amendments — rather than a single omnibus package including the entire federal budget.

Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart (R-FL) said that this means the fiscal 2022 topline is itself tentative.

“That’s what we’re looking at, but it’s going to have to go through an open process,” Diaz-Balart said. “And so who knows what it’s going to look like at the end of the day, it might be higher, might be lower.”

Those who initially opposed McCarthy’s bid before flipping their support and giving him the gavel, should they feel he has violated their agreement, will have a powerful tool to try to keep him in line — any single member can trigger a motion to vacate, calling a no-confidence vote to oust McCarthy from the speakership.

“I’m not going to play the what-if games on how we’re going to use the tools of the House to make sure that we enforce the terms of the agreement,” Roy said on Sunday. “But we will use the tools of the House to enforce the terms of the agreement.”

Republicans budget cuts could be further complicated if Senate leadership — which took the lead in negotiating the last federal budget — decides not to go along with House Republicans’ plans.

Hill declined to say what would happen under the deal if the Senate passed its own omnibus and sent it to the House for a vote.

“My experience is the Senate doesn’t care who’s in the majority over here,” Rep. Mark Amodei (R-NV) said. “They give the same amount of respect whether it’s Paul Ryan or Nancy Pelosi.”