Inside Tucker Carlson’s transformation, according to his chronicler

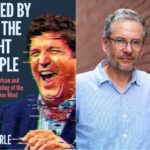

New Yorker reporter Jason Zengerle’s book, ‘Hated By All the Right People: Tucker Carlson and the Unraveling on the Conservative Mind,’ comes out Tuesday

Courtesy/Andrew Kornylak

Book cover/Jason Zengerle

In his richly reported new book, Hated by All the Right People: Tucker Carlson and the Unraveling of the Conservative Mind, Jason Zengerle tracks the evolution of the mainstream conservative journalist for The Weekly Standard, CNN and FOX News into a prominent figure in the far-right media ecosystem whose commentary increasingly descends into open antisemitism.

Zengerle, a veteran political reporter, ruminates over Carlson’s troubling transition from magazine writer to cable news pundit to his current position as a widely followed podcast host whose credulous interviews with Nazi sympathizers and Holocaust deniers, among others, have done little to dampen his influence in the MAGA movement he helped build.

In a recent interview with Jewish Insider, Zengerle, whose book will be published Tuesday, warned that Carlson’s efforts to smuggle antisemitic views into mainstream discourse should not be taken lightly.

“Tucker has credibility, and he comes across as a credible person,” Zengerle said. “That he’s giving voice to these really pretty fringe and dangerous sentiments is not to be underestimated, because people trust him.”

Whether Carlson personally believes the “awful things” he promotes, Zengerle writes in his book, “matters less than that he says them at all, and that millions of people — members of Congress, titans of industry, the president and just everyday Americans — listen to and take their cues from him.”

“What matters is that by saying these things, Carlson has finally achieved the fame, power and influence that for so long eluded him,” he adds.

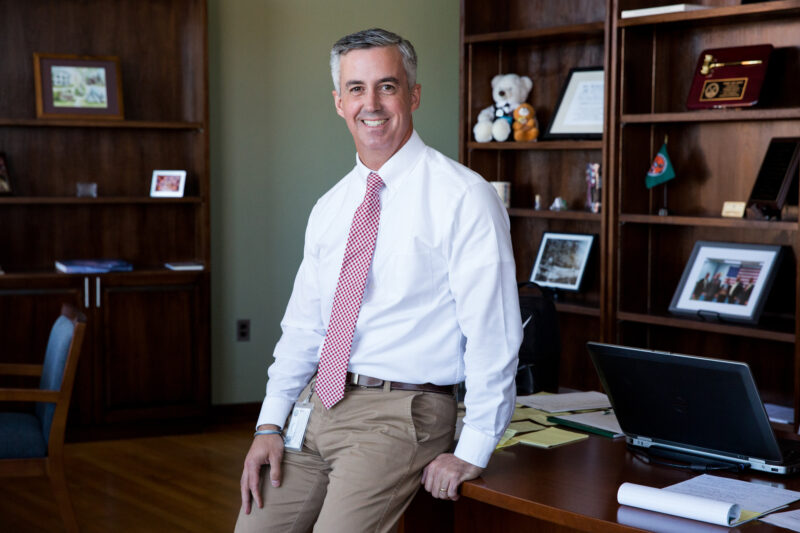

Zengerle, 52, was recently hired as a staff writer for The New Yorker, and has previously contributed to The New York Times Magazine, GQ and The New Republic, among other publications. His book on Carlson is his first.

Speaking with JI last week, Zengerle discussed Carlson’s professional ascent, his motivations for demonizing Israel and why conservative Jews are so frightened by his potential role in shaping the future direction of the Republican Party after President Donald Trump leaves office, among other topics.

The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Jewish Insider: This book has been in the works for a while. How did the idea initially come about?

Jason Zengerle: It’s been a bit of a roller coaster. The initial idea sort of came from a conversation I was having with my agent about a book I didn’t want to write, about the Republican civil war that was about to unfold. This is not long after [the] Jan. 6 [2021 Capitol riot]. The people who are going to be vying to inherit Trump supporters, because Trump was obviously a finished product, would never be coming back. And I was sort of talking to my agent about the various characters, and explaining why I didn’t think, no matter how many positions [Sens.] Josh Hawley (R-MO) or Ted Cruz (R-TX) or Tom Cotton (R-AR) took that would seem to appeal to Trump’s base, there was no way they’re ever going to inherit those voters, because they just lacked the charisma and entertainment value that Trump obviously has.

Offhandedly, I said something like, ‘You know, the only guy who really can do that is Tucker Carlson.’ That was the genesis of the idea. Then, obviously, when I started the book, Tucker was at the height of his powers. He had the highest-rated show on Fox. Trump had kind of exited the stage. And Tucker, in a lot of ways, had sort of replaced Trump, just in terms of the headspace he was occupying among both liberals and conservatives. You had this weird Tucker economy of liberal journalists and people on Twitter who would clip his show, sort of like outrage bait.

For the first couple years I was working on the book, Tucker was sort of occupying that space. And then he got fired from Fox, and everyone was predicting that he would basically suffer the same fate all Fox stars suffer when they leave Fox, which is irrelevance. Like, who thinks about Bill O’Reilly these days, right? But I thought that wasn’t going to happen. I thought Tucker was going to stay in the picture. That might have been some motivated self-reasoning on my part, because I wanted the book to be relevant. My original publisher definitely thought he was going to fade away because they canceled my contract.

JI: It certainly seems you were right in suspecting that he would continue to be not only relevant, but extremely influential during the campaign and in influencing hiring decisions for key roles in the Trump administration, as you detail in the book. He’s had a circuitous and occasionally rocky career from print journalism to cable news and now to an independent podcast. How do you view his evolution? Is there a moment where you see a clear turning point toward the type of demagogic commentator he would become, or do you think it was more gradual?

JZ: I think there are definitely inflection points in his career, and you can point to a number of them. I think one was certainly the war in Iraq. I think that had a pretty profound impact on his thinking. You know, I think he harbored some private doubts about the wisdom of going to war there, but was not really comfortable expressing them publicly, for a couple of reasons. Today, he talks a lot about how Bill Kristol and all these guys kind of misled him, and that’s why he hates them so much. At the same time, his best friend and now business partner was Neil Patel, who was working for Scooter Libby [chief of staff to former Vice President Dick Cheney]. And if you want to look at the disinformation that was put out into the world that supported going into Iraq, that was coming from Dick Cheney’s office. And I think Neil played a role in that. The fact that his best friend was sort of making the case for war, I think, made it difficult for him to oppose it. Two, the job he had at CNN at the time, on “Crossfire,” was to represent the right and the Bush administration — so just from a practical standpoint, he had to kind of support the war.

But anyway, the fact that things went so badly for Tucker at CNN, I think, made him reexamine a number of his priors and a lot of his time in his early career, when he was at The Weekly Standard and even after he had started writing for Talk and Esquire. There was such an effort among people like Kristol to excommunicate Pat Buchanan from the conservative movement. I think what happened with Iraq made Tucker reconsider Buchanan a bit, and he sort of saw that, ‘OK, well, I actually think this guy was right about foreign policy, and maybe he’s right about some other stuff as well.’ I think that led him to become much more hawkish on immigration.

I think that what happened with Jon Stewart and CNN was a pretty big inflection point in the sense that the public humiliation he suffered, obviously, was difficult for him. But I also think he felt that his friends in the elite D.C. political and media circles didn’t come to his aid the way he would have liked. That started to breed a certain resentment he felt toward them that really grew as his career limped along. It made it a lot easier for him, when Trump came on the stage and started attacking the swamp and D.C. elites, to join in on those attacks, because I think he still nursed a grudge. So you can see things gradually, but you can also point to these crossroads moments, as well.

JI: You write that, while you didn’t know Carlson well, he often served as an “eager interview” subject and source for your stories over the years. Still, he didn’t agree to any interviews for your book. Why do you think that was?

JZ: I think it really is that Robert Novak expression: “a source, not a target.” I think he plays that game.

JI: There’s an interesting recollection in the prologue about your occasional interactions with Carlson when he would stop by the New Republic offices back in the late ’90s during your time as an intern there. You describe him then as a “hotshot young writer for The Weekly Standard,” and say he “seemed so much older, wiser and worldlier than we were.”

JZ: Maybe it didn’t take much to impress me. But the thing about him back then — and the thing I think others admired about him and looked up to him for — was that he was really courageous. The targets he picked, whether it was Grover Norquist or George W. Bush — it took guts to do that as a conservative journalist, and that was admirable.

JI: You write in the book that Carlson has “come a long way from the days when he described himself as a pro-Israel, Episcopalian neocon.” On his show now, he regularly promotes antisemitic tropes and conspiracy theories, incessantly attacks Israel and hosts neo-Nazis and Holocaust deniers for friendly interviews. Do you have insight into what sparked this openly antisemitic streak?

JZ: It’s funny, someone who’s close to him was telling me that they thought this basically started with his conclusion that all the people who were opposed to him and Trump, post-2016, were big Israel supporters. So Tucker’s like, ‘Alright, I’m just going to piss these people off by going after Israel,’ and that’s kind of where it started. I don’t know if that’s the case.

I mean, Bill Kristol looms so large in his mind and in his own story. The story that he tells people, and the story I think he tells himself, is he was misled and used and kind of exploited by the neocons, that he was this young, naive, innocent writer who got just basically used to get us into a war and support free trade deals and do all these things that hurt the white working class in America, and that what he’s doing now is his penance. And I think that’s not a true story. I don’t think that’s what happened.

Kristol is just such a huge figure in his own mythology. Even before Tucker went in this direction, he was really close to Kristol. He really looked up to him. He was his first boss, and I think he had a real impact on Tucker’s career. But now, Tucker wants that all to be a negative impact. He did an interview recently with his brother, Buckley Carlson, where he talked about how Kristol hates Christians. Bill Kristol, who hired Fred Barnes and took vacations with Gary Bauer. He’s recast all this stuff.

JI: Do you think Carlson’s hostility toward Israel and descent into nakedly antisemitic vitriol, such as when he called Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky “ratlike” and “a persecutor of Christians,” is motivated by more than just resentment of those he believes have spurned him? There’s been a lot of attention recently about a generational turn away from Israel on the right, which raises a question of whether he’s opportunistically tapping into that or directly influencing it.

JZ: I guess it’s both. I do think he’s making the calculation that that is where the energy is, and therefore he wants to make sure he stays out in front of it. He has a very good political radar and good professional radar. I think the Nick Fuentes episode was him recognizing he was in this feud with this guy, and he was losing, and him sort of deciding you cannot be successful in conservative media or conservative politics these days unless you have the support of these neo-Nazis. Unfortunately, it’s not going to work for you, and so he needed to get back on their good side. I think that’s part of the calculus.

At the same time, I think he is influencing some of these people, maybe not the hardcore Nick Fuentes supporters, but young conservatives who, you look at what happened or what’s happening in Gaza and had questions and qualms and concerns. And then Tucker is out there — and Fuentes is out there as well — making the argument about how Gaza is wrong, but taking it so much further than that, and going into these really ugly corners of anti-Israel sentiment and taking them to those places.

Now, I don’t want to get too far afield here, but that JD Vance talk at Ole Miss, where the frat boy asked that question about Israel persecuting Christians — that was a real light bulb moment for me. That this stuff had penetrated that deep that you have this guy who appears to be your regular old SEC frat boy saying this stuff. And I think Tucker is responsible for a lot of that, because that’s something he did at Fox, and he continues to do. He’s really good at taking ideas and arguments and even just stories from extreme, far-right fringy areas, often on the internet, and smuggling them into the mainstream. I think he’s doing that with the Israel stuff and with the Jewish stuff.

JI: His interview in 2024 with Darryl Cooper, the self-proclaimed podcast historian and Holocaust revisionist who has described Winston Churchill as the “chief villain” of World War II, seems an early instance of that effort.

JZ: That’s a perfect example. You have to be really steeped in this stuff to see what this individual is saying and doing and the rhetorical tricks they’re playing. Tucker just brings and vouches for these people, and I think that’s pretty dangerous. Tucker has credibility, and he comes across as a credible person. The fact that he’s giving voice to these really pretty fringe and dangerous sentiments is not to be underestimated, because people trust him, and it validates them.

JI: There’s been some intermittent speculation about whether Carlson will run for president. Do you have any thoughts on that?

JZ: I don’t think he just wants to be a podcaster. I don’t think that’s his goal here. I think he has a real vision for what he wants this country to be, and he wants to achieve that vision, and if it turned out that running for office was the way to do that, I could see him doing it. I don’t think it’d be his first choice. I think right now, he has a nice, nice setup where he obviously has a president who listens to him. Maybe even more importantly, he has a vice president who I think he’s even closer to and more in alignment with. Just sort of thinking through the steps, as long as he thinks JD Vance and he are on the same page ideologically, and as long as he thinks JD Vance is capable of being elected president, that he has the political talent to pull that off, I can’t imagine him doing anything on his own.

But if one of those two things changes, and I think it’s quite possible that the latter becomes a sticking point — if Tucker at some point were to conclude that JD Vance actually isn’t capable of being elected president and that his his ideological project is in jeopardy — I could certainly see him taking a shot at it. The way you would run for president now, it’s so different from how you had to do it before. He could probably do a lot of it from his podcast studio. But I think what’s more important is just understanding why he would do it, which is sort of the bigger point. He really does have a project he’s working on, and I think he’ll do what he thinks is necessary in order to bring that project to fruition.

JI: How would you characterize that project?

JZ: He wants the United States to look like it did in the 1950s. I think he’s very much in alignment with Stephen Miller. Beyond the immigration stuff and us being a much whiter country, I think he wants to return to traditional gender roles.

JI: While some Republican lawmakers have spoken out against Carlson, it seems notable that Trump and Vance have both so far refrained from explicitly distancing themselves from him.

JZ: There’s this weird thing going on where certain Jewish conservatives feel like, as long as Trump’s there, everything’s going to be fine. You know, his grandchildren are Jewish, he might say some stuff, he might do some things, but at the end of the day, the worst-case scenario will never occur. They view Tucker as this bad influence on Vance, and if they can just get rid of the bad influence, Vance will be OK. But they’re really terrified of Tucker. They’re really terrified of what comes after Trump. And they’re terrified that Tucker will have a major influence on whatever comes after Trump. They’re worried about the influence he has on Vance. They want to believe that Vance would be OK, left to his own devices. They think Tucker is leading him in a bad direction, and therefore they need to take out Tucker.

I think it goes beyond Israel. I think it’s genuine fear about what it would mean to be Jewish in the United States. I’ve been talking to some of these folks recently. I think it’s a real, deep-seated fear about, in Tucker Carlson’s America, what would it be like to be Jewish here?