New book highlights America’s ‘Family Unfriendly’ culture — in contrast with Israel

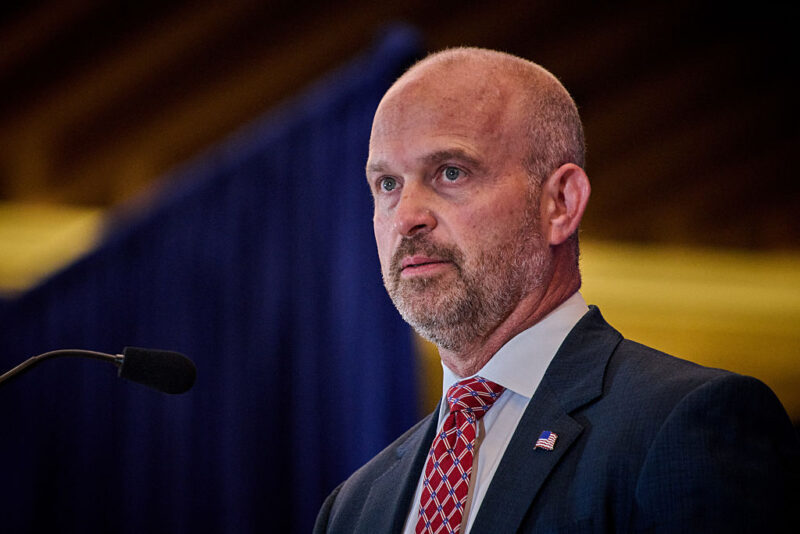

Tim Carney dedicates a chapter of his book to investigating how Israel came to be the most fertile of the world’s wealthy countries: ‘Culture is the most important thing’

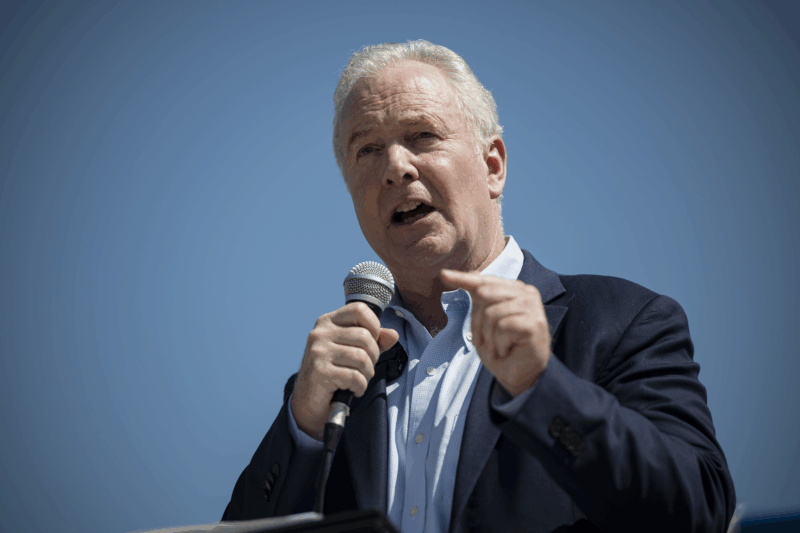

While Tim Carney was working on his new book, Family Unfriendly: How Our Culture Made Raising Kids Much Harder Than It Needs to Be, he joined a Catholic pilgrimage to Israel and found himself in the country with the highest fertility rate of the world’s wealthiest nations.

Israel has a birthrate of three children per woman, according to the most recent data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. That’s almost twice the OECD average of 1.58 and significantly more than second-place country Saudi Arabia at 2.43 or the U.S., in 18th place with a birth rate of 1.66.

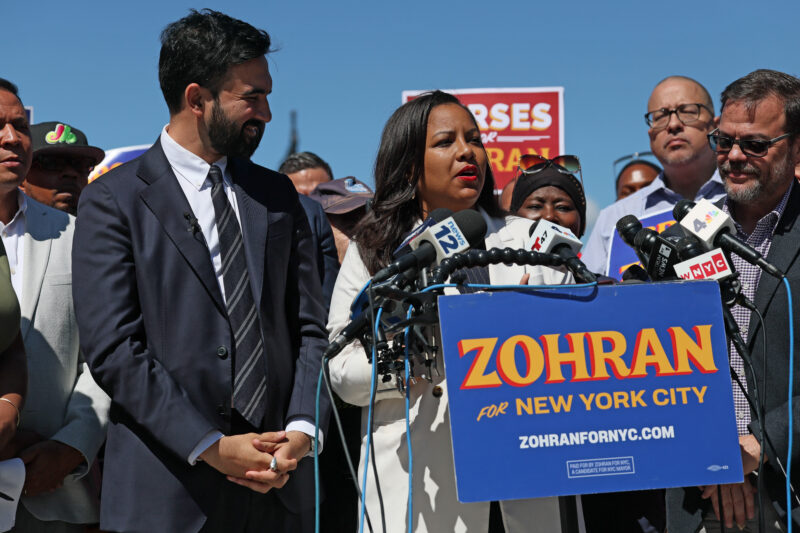

Carney, an American Enterprise Institute fellow and Washington Examiner columnist — but perhaps most importantly to his latest project, a father of six — extended his visit to Israel, seeking to find out Israel’s secret, and how it can be replicated. He spoke with secular parents at a public playground in Tel Aviv and Orthodox parents on the streets of Jerusalem about why they had kids and how they’re raising them.

As anyone sitting next to a parent on an El Al flight may have observed, it is perfectly natural for an Israeli to hand his or her baby to a stranger so he or she can use the restroom. It’s also quite common in Israel for a fourth grader to walk home from school without an adult and pick up a younger sibling from preschool on the way.

It’s phenomena like these that helped Carney reach his conclusion that culture, rather than policy or even religion, is behind Israel’s exceptional fecundity, and Carney decided to dedicate a chapter of his book to the Jewish state.

He spoke with Jewish Insider this month about his new book and his findings.

Jewish Insider: What did you find so interesting about Israel that you decided to write a whole chapter about it?

Tim Carney: No OECD country even competes with Israel on people having babies. It’s even more interesting when someone showed me data on Israel that broke it down by [population] category, and even for secular Jews it’s about 2.0 – more than the U.S. – so you couldn’t chalk up the higher birth rate to religious teaching or something specific about the more Orthodox [Jews].

JI: What did you learn on the visit?

TC: I got to see the culture a little bit on my pilgrimage. I grew up in New York, and the only people who compete with New Yorkers in willingness to offer their opinions are the people of Tel Aviv and Jerusalem!

I interviewed people who identified as totally secular but many had three kids. One guy told me “God has nothing to do with our family planning.” One Orthodox guy in Jerusalem said, “No, it’s just about religion,” and we had this back and forth and he said, “OK, it starts with religion.” That helped me see it.

The broader image I came up with is a garden where the central tree is religion. God’s first commandment is “be fruitful and multiply.” But there are other trees. One person talked about the tribe, another about the preservation of the Jewish people throughout history and from geopolitical threats.

These three trees create a garden and a family ecosystem, where, even if you don’t eat from all three of these trees, you still live in a family-friendly environment.

JI: So those are reasons for people to want to have more children, but research shows a gap between how many children women want and how many they actually have. What makes Israelis take that extra step?

TC: I used to live in Silver Spring, Md., right next door to Kemp Mill [where there’s a large Orthodox Jewish community]. One year, as part of my reporting, I went to the Purim festival at one of the big synagogues there. This one man said to me, in trying to explain how pro-family he thought Israel was, that the bus drivers in Israel have a real affection for little kids. It’s a beautiful image that everybody out there is looking out for your kids and trying to help you.

I’m a fellow at AEI, where we’re doing public policy research. A lot of my friends try to make economic policy about what is going on. I think sometimes culture, which is less measurable, really needs to be considered. Israel really drives home that culture is the most important thing.

JI: How is that culture expressed?

TC: About 70% of Israeli parents reported having help from their own parents in raising kids. That is incredibly valuable, and it’s half that rate in Europe. The U.S. is closer.

There’s a general free-range-ness of Israeli kids. There was one guy I spoke to who was not fluent in English and was somewhat indelicate in saying “here you don’t need to raise your own children.”…I saw sixth graders Rollerblading around Dizengoff Square on a Sunday night without needing parental supervision. Parents were bringing kids to a restaurant that would be too nice for kids in the U.S. I spoke at a conference recently and said that there would be many kids at this conference if it were in Israel.

There’s more of an expectation that you’ll help some stranger’s kid. One guy told me that, when crossing the street, a 6-year-old will wait for the next adult to help him. That is something that doesn’t happen in the U.S.; if you try to help a strange 6-year-old, someone might think you’re a creep.

JI: The expectation that strangers in Israel will help you with your kid — something that I can definitely attest to as an Israeli mom — seems like an indicator of a high-trust society. Do you think trust correlates with family-friendliness?

TC: The U.S. is steadily becoming a lower and lower trust society, and that has massive negative consequences. A great sign of a healthy society is if kids’ bikes are scattered on the front lawns. I saw that even in the Old City of Jerusalem; there’d be a little courtyard with little kids’ bikes not locked up.

High trust vs. low trust society is something that has its own momentum. I think we are slipping in the opposite direction…It would be incredibly complicated to tease out the causes of it.

Being a higher-trust society makes it much easier to raise children.

JI: Are there Israeli government policies that you think the U.S. should adopt to be friendlier to families?

TC: The OECD tracks the percentage of GDP that goes to welfare spending and specifically on parents and children, and Israel is in the middle of the pack on both of those. A lot of countries that spend a lot more on that stuff don’t have higher birth rates and their birth rates have fallen.

It could be that Israel picks the right policies and spends more efficiently, but the way I look at it is that the difference has to do with culture. Certain policies will nudge culture in a more family-friendly direction, and those will be the ones that matter.

What doesn’t help is just subsidizing childcare. It certainly doesn’t help married women have more children. It’s just a subsidy for work. Giving people large child allowances or tax credits definitely has some positive effect, though it’s super expensive…

My theory is that removing uncertainty from the lives of would-be parents is one of the most important things that policy can do — knowing that being pregnant and having a baby won’t make you poor. [Governments] don’t have to cover the whole thing, but you can estimate how much it costs. We have zero transparency on any [health-care costs]…It’s even worse for parents. When my wife gave birth there was an out-of network anesthesiologist on duty, and they hit us with a $10,000 bill. That uncertainty is built into the system.

We should make birth free as a policy. That could be a relatively cheap way of removing the uncertainty.

Another policy to make the U.S. more family friendly would have to do with sidewalks and walkability and bike-ability. Anything to make it easier for parents to be more free-range and allow kids to independently play. At a lot of schools now, it’s a special exception if your kid walks. You have to fill out forms.

JI: It used to be fairly common for American kids to walk to school on their own — before either of us was in school, but you see it in books and movies from the mid-20th century. Ramona Quimby walked to kindergarten. What changed?

TC: It’s the way suburbs were built. Cars got cheaper, and they represented freedom. We’re a big country with tons of room and living further and further out became more desirable.

Stranger danger in the U.S. really kicked into gear when I was a kid. There were high-profile abductions that took place. The idea got implanted that there is a kidnapper around every corner in the late ’80s. I think that really discouraged kids from walking.

Back in the 1960s, kids were four times more likely to walk to school than they were 10 years ago. It’s never been the case that most American kids walked or biked, but it was 40% then and 10% around 10 years ago.

JI: If the argument is that government is not the main driver of family friendliness, what should parents or communities do?

TC: Embrace the fact that child-rearing is a communal undertaking. Don’t be afraid to impose your kids on other people by sending them over, and communicate clearly that other people can discipline or correct your kids. So many people my age remember being yelled at by another mom on a porch, and that wasn’t considered being a busybody. We need to set that norm — to borrow a phrase, “it takes a village.” Say to people, “my kid is running around the neighborhood; this is why I think it’s safe. Your kid can join. The more the merrier.”

JI: Do you think religion makes a difference?

TC: America has lots of family-friendly subcultures. Kemp Mill is one in my book. There are also Mormon circles in Utah and Idaho.

It’s not broadly the case in Catholic circles, but we run in specific Catholic circles where we have six kids and we have friends with six or eight. We are more family-centered. Our weekend is more likely to have a barbecue cookout where the kids run wild.

Mormon institutions like Brigham Young University not only accommodate parents, they declare that they will accommodate parents. It is very common to have kids while an undergrad at BYU. Lots of religious communities explicitly go out of their way.

It’s not so surprising that religious communities where members regularly attend services have significantly more kids than non-religious communities, above the replacement rate [of two children]. Catholics who go to church every Sunday are at three kids; Catholics who don’t are closer to the national average. Belonging to a religious congregation gives you a sense of belonging and connects you to people. They’re there when you’re in trouble. It has more to do with that than religion.

JI: Do you think there needs to be pushback against the increasingly common deferral of marriage and having children?

TC: The delay in marriage is the major cause of the reduction of birth rates. If somebody wants three kids, gets married at 30 and waits a couple of years, there’s a higher likelihood that biology won’t cooperate with their plans. That’s a major thing.

I think our dating and mating culture in the U.S. is totally broken, even more than our career-mindedness. The dating apps fit into a broader cultural change that makes everybody totally dysfunctional at getting together. People become perfectionists because of apps and afraid to ask someone out in person because they haven’t gotten double secret consent.

I’m better at diagnosing problems than finding solutions, but [we need to] normalize dating friends of friends and just pound the point that nobody is ever ready to have kids. There’s no perfect time, so anytime is as good as any other.