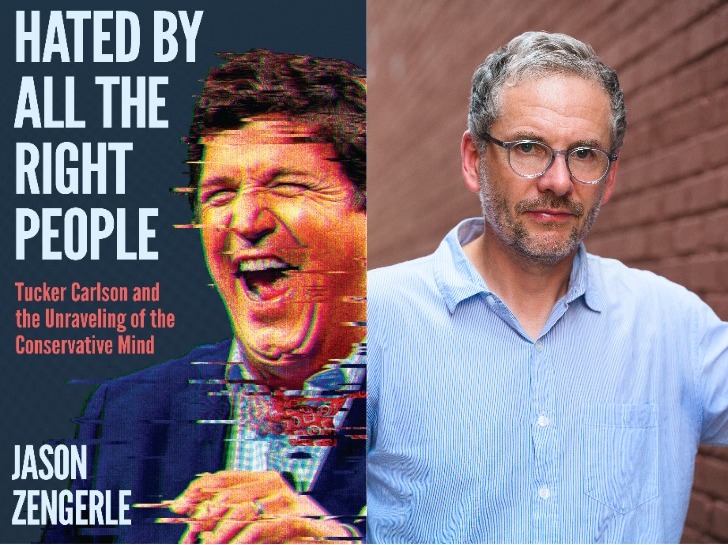

Ben Smith talks state of journalism

The veteran journalist and co-founder of Semafor joins JI’s Limited Liability Podcast

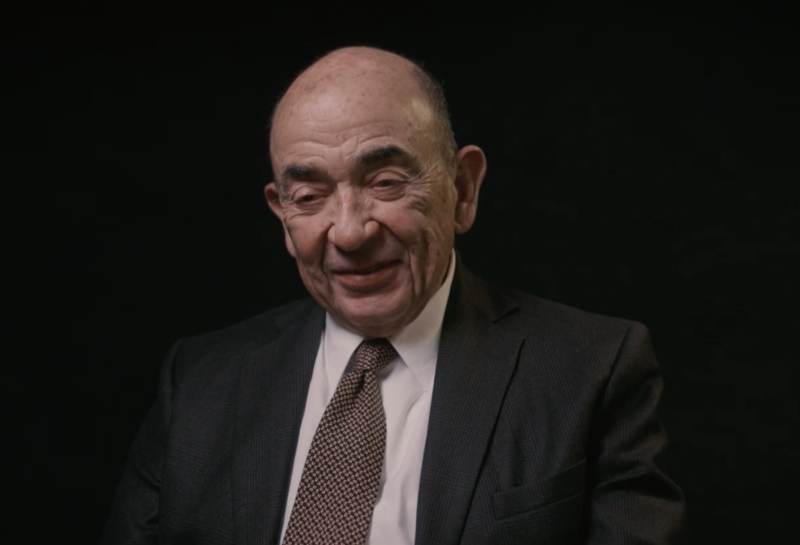

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Journalist Ben Smith

Ben Smith has worn many hats in his journey from young New York City Hall reporter to founder of a media company. But everywhere the veteran journalist goes — from The New York Sun to Politico to BuzzFeed to The New York Times — he has brought a signature scoop-focused intensity. As he prepares to launch his newest venture, Semafor, Smith joined Jewish Insider’s “Limited Liability Podcast” for a discussion on the state of journalism, cutting his teeth in New York’s infamous Room 9 and how he looks to build a new media company.

Below are excerpts from the episode.

Twitter’s impact on institutions:

“I don’t think journalism is particularly different from anything else. Everybody from television networks, to politicians, to businesses suddenly felt this new challenge. People could see inside the workings and demystify these institutions, which, I think, was a big problem for the media, because we would pretend we were better than we were, or doing something sort of special when it really was just kind of messy, hard work.

“I think the Democratic Party and the Republican Party are sort of meaningless institutions in the face of social media. It’s certainly been unbelievably destabilizing. I think some of the most inspiring versions of that destabilization, like the Arab Spring, were pretty quickly stamped out. But, I think, you had these, obviously, pretty weak establishments that sort of crumbled under the pressure of this disruption. [It’s] too soon to say, basically, whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing.”

Twitter’s impact on media:

“It’s not like the media wasn’t making mistakes and being ideological and bumbling and biased before. It’s just now, it’s all much more on display, like we were always idiots, it’s just on display now. And people can attack it…

“You’re just a normal person running around trying to figure something out. And so if you asked me at noon what I know, it could all be wrong, but by 6 p.m., maybe I figured it out. And by the time it’s in the paper the next morning, it’s a reasonable approximation of reality. The thing is, now, all that bumbling around that I was doing during the day is on public display, and people are like, ‘Oh my God, these people are total idiots. They don’t know any more than we do.’ The thing is, that’s always been true. It’s just that now it’s on display. And I think all journalists can do is just be like, ‘Yes, we don’t have any special magic powers that you don’t, we’re just trying to figure stuff out.’ Which I think is painful, because I think journalists like to have this special mystified status.”

Building Semafor:

“I think in terms of what we’re trying to build at Semafor now, we want to just acknowledge the reality that people connect more and audiences connect more with individuals than with a faceless brand, and lean into that and give great journalists an opportunity to speak really directly to an audience and not try to aggressively come in-between that and keep journalists in their box.

“I think the other side of that is that you can do it with a level of honesty and transparency where you’re not saying, ‘the view of The New York Times is that Donald Trump is a racist. Like, it’s just, who wants to ask these big institutions to have these views? They’re not the Catholic Church. They don’t need to hand out encyclicals.

“But I am interested in what Maggie Haberman thinks. She knows a lot, she’s an expert. I am interested in what Wes Lowery thinks. I am interested in what David Leonhardt thinks. All sorts of people, and they disagree with each other. And I disagree with them sometimes, but I’m interested in having disagreements with a smart journalist who knows what they’re talking about. I’m made uncomfortable when an institution takes an official posture. I don’t even know what to do with that.”

Starting at City Hall:

“I got to City Hall and, and because I was working for The New York Sun, which was this sort of weird, new kind of conservative newspaper that had descended from the Jewish Forward, [I] got a desk not in the real press room, Room 9, that kind of legendary high-ceilings press room just to the right of the door as you walk in, but in this basement room. It was Room 4A, and it was sort of filthy and it was where worse stuff that nobody knew what to do with went and there were squirrels sometimes coming in and out…

“They started running out of space upstairs. And so the most junior New York Post and Newsday reporters were down there, and that was Maggie Haberman and Glenn Thrush. So really, my main experience was like, ‘Whoa, these City Hall reporters are like, unbelievably smart and aggressive and fun and good at their jobs. I can’t imagine how good the people upstairs are.’ But in fact, Maggie’s a generational talent and I was just lucky to be sitting across from her. And I just learned an enormous amount from listening to her talk on the phone, but also, really compete. They were friends, but also competed very intensely [with] people who just turned out to be a couple other really great reporting talents of the generation.”