The Florida Board of Governors rejected Ono’s confirmation, citing his inadequate response to antisemitism at the University of Michigan

Bryan Bedder/Getty Images for Anti-Defamation League

Call Me Back podcast host Dan Senor moderates a session with WashU Chancellor Andrew D. Martin and University of Michigan President Santa Ono at the ADL Never is Now event at Javits Center on March 03, 2025 in New York City.

In an unprecedented move, the Florida Board of Governors rejected the confirmation of Santa Ono, the former president of the University of Michigan, as the University of Florida’s next president.

During a three hour meeting on Tuesday, Ono was questioned by the board, which oversees the state’s 12 public universities, about an anti-Israel encampment last year that remained on the Michigan campus for a month, as well as his stance on antisemitism.

Alan Levine, vice chair of the board, grilled Ono about what he described as an inadequate response to antisemitism at Michigan during Ono’s tenure to the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas attacks in Israel, The Gainesville Sun reported.

“What happened on Oct. 7 deeply affected the members of my community and me personally, and so at UF I would be consistently focused on making sure antisemitism does not rear its head again,” Ono responded.

Ono also faced criticism from conservatives on the board for his longtime support of diversity, equity and inclusion programs while leading the Ann Arbor university, although Ono has said he would not bring DEI to the Gainesville school. In March, under pressure from the Trump administration, Ono eliminated centralized DEI offices at Michigan — which have come under intense scrutiny on campuses nationwide for failing to address rising anti-Jewish hate, and at times perpetuating it.

Ono denounced antisemitism in an Inside Higher Ed op-ed last month. He wrote, “I’ve worked closely with Jewish students, faculty and community leaders to ensure that campuses are places of respect, safety and inclusion for all.”

Prominent conservatives who raised objections to Ono included Donald Trump Jr. and Florida Reps. Byron Donalds, Greg Steube and Jimmy Patronis. His confirmation was not publicly opposed by the state’s Republican governor, Ron DeSantis.

The decision by the 17-member Florida Board of Governors comes a week after UF’s Board of Trustees had unanimously approved Ono as its president-elect. The vote to confirm Ono failed 10-6, the first time that the Board of Governors has ever voted down a university trustee board’s leadership selection.

Ono was seen as an ally of Michigan’s pro-Israel community who was quick to condemn acts of antisemitism — leading to pro-Palestinian vandals attacking his home on the one-year anniversary of Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack. In November, he visited the Nova Music Festival Exhibition in Detroit alongside several students.

Under the leadership of Ben Sasse, a former Nebraska senator who served as UF president until stepping down last year, Ono wrote that the school has been a “national leader in this regard — setting a gold standard in standing firmly against antisemitism and hate.” Sasse was among the first university presidents to immediately condemn Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack — as other campus leaders seemed paralyzed over how to respond.

“That standard will not change under my leadership,” Ono said last month. He pledged to “continue to ensure that UF is a place where Jewish students feel fully supported, and where all forms of hatred and discrimination are confronted clearly and without hesitation.” Nearly 20% of the university’s student body is Jewish.

The search for University of Florida’s 14th president will now start over.

Plus, the NYC candidate who won't say 'Jewish state’

Andrew Harnik/Getty Images

A police officer stands at the site of a fatal shooting at the Capital Jewish Museum on May 22, 2025 in Washington, DC.

Good Friday morning.

In today’s Daily Kickoff, we cover comments by Zohran Mamdani at last night’s UJA-Federation of New York town hall with the leading Democratic candidates in New York City’s mayoral primary and report on the Trump administration’s move to strip Harvard University of its ability to enroll foreign students. In the aftermath of Wednesday’s deadly shooting outside the Capital Jewish Museum in Washington, we talk to friends of the victims, Yaron Lischinsky and Sarah Milgrim, and report on comments by pro-Israel leaders connecting the murder to anti-Israel advocacy on the political extremes and highlight a statement by 42 Jewish organizations urging additional action from the federal government to address antisemitism. Also in today’s Daily Kickoff: Sen. John Cornyn, Rep. Josh Gottheimer and Ambassador Yechiel Leiter.

Ed. note: In honor of Memorial Day on Monday, the next edition of the Daily Kickoff will arrive on Tuesday, May 27.

What We’re Watching

- The fifth round of nuclear negotiations between the U.S. and Iran will take place today in Rome. Israeli Strategic Affairs Minister Ron Dermer and Mossad Director David Barnea are also set to meet with Middle East envoy Steve Witkoff in Rome to coordinate Israel’s views with the U.S.

- Rep. Ritchie Torres (D-NY) will deliver the keynote address at the 51st commencement ceremony of Touro’s Lander Colleges on Sunday at Lincoln Center.

What You Should Know

A QUICK WORD WITH JOSH KRAUSHAAR

In a series of upcoming Democratic primaries, Jewish and pro-Israel groups are deciding whether to press their political case and go on offense behind stalwart allies — or take a more cautious approach, focused on preventing candidates that are downright hostile to Jewish concerns from emerging as nominees, Jewish Insider Editor-in-Chief Josh Kraushaar writes.

It’s an unusual place to be in. Until recently, most Democratic candidates were reliably attuned to Jewish communal interests, and there wasn’t much of a need for groups to play in primaries, except in rare situations. That changed with the emergence of the anti-Israel Squad of far-left Democrats, which led pro-Israel Democratic groups like DMFI to step up and support mainstream candidates, and pushed AIPAC to launch a super PAC to become much more involved in direct political engagement.

Now, even the issue of fighting or speaking out against antisemitism — far from the more heated debate over Israel policy — is no longer a consensus issue for Democrats. Senate Democrats (when in charge of the upper chamber) hesitated to hold hearings on campus antisemitism, a leading candidate for mayor of New York City declined to sign onto a legislative resolution commemorating the Holocaust and an increasingly credible New Jersey gubernatorial candidate has declined to distance himself from Louis Farrakhan.

What was once the extreme has now come uncomfortably close to the Democratic mainstream. The urgency of ensuring most candidates condemn antisemitism and anti-Israel radicalism wherever it rears its ugly head was made clear after the horrific murder on Wednesday night of two Israeli Embassy employees by a terrorist with a radical, anti-Israel background. Far too often, the growing number of threats to Jews along with the rise of anti-Israel sloganeering featuring antisemitic hate or adoption of terrorist symbols has been met with a benign acceptance.

That’s made the tactical decisions from outside Jewish and pro-Israel groups involved in politics a lot more significant. There are a number of Democratic primaries coming up featuring a stalwart ally of the Jewish community, an anti-Israel candidate with checkered history on antisemitism and a middle-of-the-road candidate whose record on these issues is respectable, but not always reliable.

Take next month’s New Jersey governor’s primary. Rep. Mikie Sherrill (D-NJ), seen as the front-runner, has compiled a generally pro-Israel record in Congress but hasn’t stuck her neck out as much as her Democratic colleague, Rep. Josh Gottheimer (D-NJ). Gottheimer has yet to catch momentum in the crowded primary, and one of the other credible challengers is Newark Mayor Ras Baraka, whose condemnation of Israel’s war in Gaza and praise for Farrakhan is viewed as beyond the pale.

At a certain point, do Jewish groups rally behind the center-left front-runner to block the more problematic candidate, or stick with the most supportive candidate?

The New York City mayoral primary next month provides another key test. State Assemblyman Zohran Mamdani is the favorite of the DSA base, and thanks to strong support from that far-left faction, is polling in second place. But due to his high profile and moderate pro-Israel message, former Gov. Andrew Cuomo looks like the clear front-runner — even as Jewish voters haven’t yet consolidated behind him in the crowded field.

To Cuomo’s benefit, New York City mayoral primaries have a ranked-choice system that prevents a candidate with a small but passionate base from winning a small plurality in a crowded field. In theory, that should help Cuomo. But as the leading moderate candidate in the race, he could also benefit from consolidating the centrist vote, which is still up for grabs.

Within the sizable Jewish constituency in New York City, Cuomo faces pushback from some Orthodox voters still angry about the then-governor’s lockdowns and expansive COVID-19 restrictions during the pandemic, making his pitch in support of Israel and against antisemitism far from a slam dunk in certain circles. His resignation from the governorship amid allegations of sexual misconduct is also a factor for some Jewish voters, as well.

But if pro-Israel, Jewish voters divide their support among other candidates, it could help Mamdani, whose record is the least palatable to these same constituents.

The fact that many Democrats in New Jersey and New York City, two places with among the largest concentrations of Jewish voters in the Diaspora, are not automatically stalwart allies of mainstream Jewish interests, is itself a sign of the changing political times and the evolving nature of the Democratic Party. It may also explain why there appears to be more of an effort to play defense — a focus on blocking the most objectionable candidates from winning high office — rather than hoping for the best, and seeing where the chips fall.

TYING IT TOGETHER

Pro-Israel leaders link anti-Israel advocacy to fatal shooting

Pro-Israel leaders and lawmakers in the United States on Thursday connected the killing of two Israeli Embassy employees outside the Capital Jewish Museum in Washington to the anti-Israel advocacy seen on the political extremes throughout the country since the Oct. 7, 2023, attacks, characterizing it as a culmination of such rhetoric and, in some cases, the failure of some politicians to denounce it, Jewish Insider’s Marc Rod and Emily Jacobs report.

What they’re saying: Sen. John Fetterman (D-PA) told Jewish Insider that the attack should be a signal to the left that it needs to rethink its rhetoric on Israel and Zionism. He compared the anti-Israel movement in the United States to a “cult” that has been stoked online and is using inherently violent slogans while its members “try to hide behind this idea that it’s free speech to intimidate and terrorize members of the Jewish community.” A coalition of 42 Jewish organizations, in a statement, described the murders as “the direct consequence of rising antisemitic incitement in places such as college campuses, city council meetings, and social media that has normalized hate and emboldened those who wish to do harm.”

Hill talk: Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) called on the Justice Department and the FBI to investigate the political organizations that Elias Rodriguez, the suspect in the shooting outside the Capital Jewish Museum, claims to be an active member of, Jewish Insider’s Emily Jacobs reports.

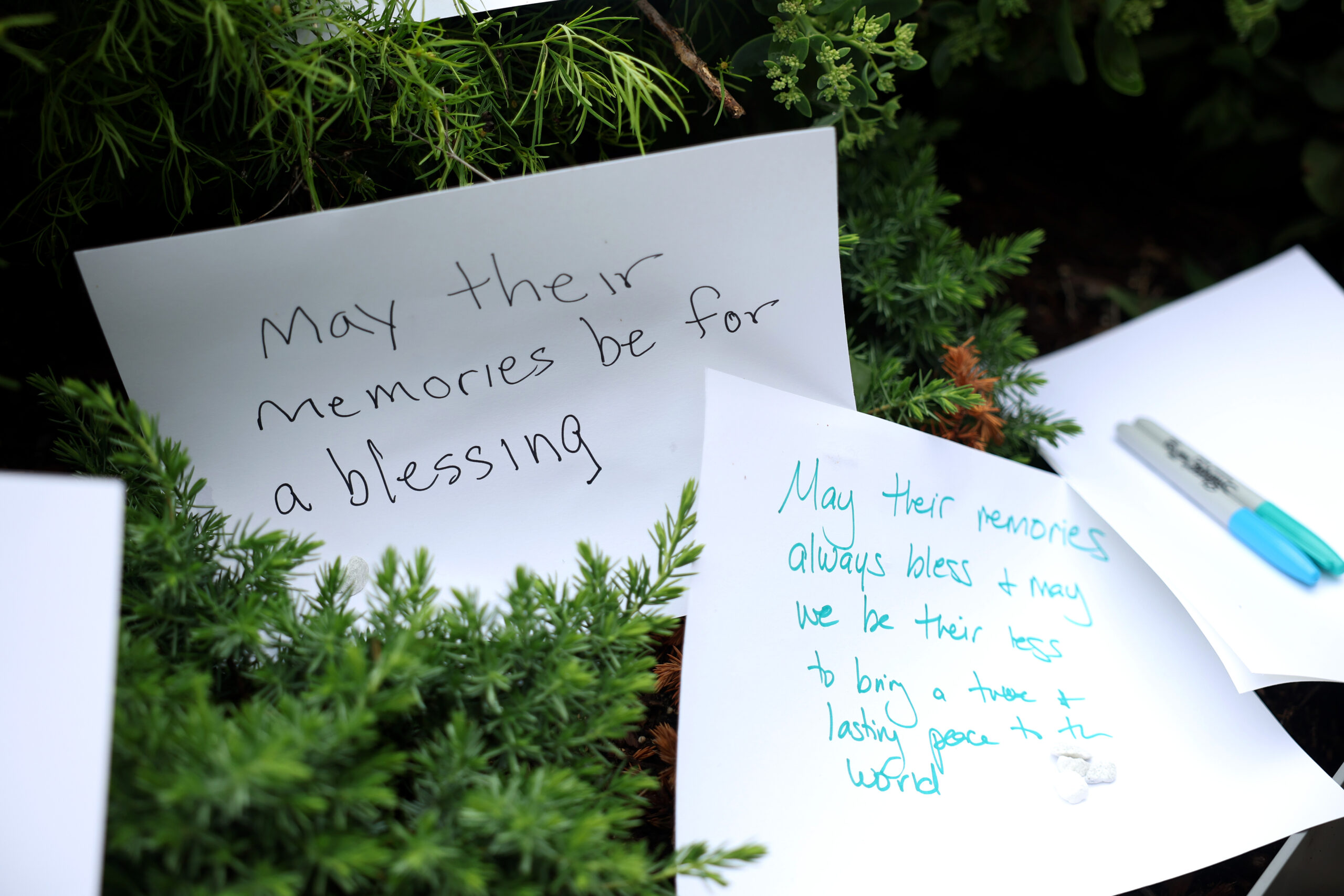

fondly remembered

Israeli Embassy victims remembered as ‘the perfect diplomat’ and ‘committed to peace’

“The perfect diplomat.” That’s how a former colleague and friend of Yaron Lischinsky remembered him on Thursday, the day after the Israeli Embassy staff member was shot dead alongside his girlfriend, Sarah Milgrim, outside of the Capital Jewish Museum in Washington as the couple was leaving an event for young diplomats and Jewish professionals hosted by the American Jewish Committee. “He was diligent and went to D.C. to pursue his dream,” Klil, who interned with Lischinsky, 29, at the Abba Eban Institute for Diplomacy and Foreign Relations at Reichman University in Herzliya, Israel, in 2020 and requested to be identified only by her first name, told Jewish Insider’s Haley Cohen.

Cherry blossoms: The pair mostly lost touch after the internship, when Lischinsky moved to Washington to work at the Israeli Embassy after pursuing a masters’ degree at Reichman. But their interest in Japan kept the two connected via social media, where they would share cherry blossom photos — Lischinsky’s came each spring when the Japanese trees bloomed on the Tidal Basin in Washington. Klil shared her cherry blossom photos from London, where she was living after the internship. “We had a shared experience around that,” she said. Recently, Lischinsky’s Instagram posts featured more than cherry blossoms. Klil took note of the photos he had been posting, posing together with Milgrim. The couple met while both working at the embassy.

Remembering Milgrim: Milgrim, 26, was remembered by a former colleague and friend as “bright, helpful, smart and passionate.” “Sarah was committed to working towards peace,” said Jake Shapiro, who worked with Milgrim in 2022-23 at Teach2Peace, an organization dedicated to building peace between Palestinians and Israelis. “One small bright spot in all of this is seeing both Israelis and Palestinians that knew Sarah sending their condolences and remembering her together,” Shapiro told JI. That gives him hope that a “more peaceful reality is possible.”

COMMUNITY CALL

Jewish community urges additional action from federal government following D.C. shootings

A coalition of 42 Jewish organizations issued a joint statement on Thursday urging additional action from the federal government to address antisemitism in the United States following the killing of two Israeli Embassy staffers outside the Capital Jewish Museum in Washington, and particularly expanded funding for a variety of programs to protect the Jewish community, Jewish Insider’s Marc Rod reports.

What they’re asking for: The demands include a call to massively expand funding for the Nonprofit Security Grant Program to $1 billion, from its current level of $274.5 million. The groups also called for additional funding for security at Jewish institutions, for the FBI to expand its intelligence operations and counter-domestic terrorism operations and for local law enforcement to be empowered to protect Jewish establishments. And they called for the federal government to “aggressively prosecute hate crimes and extremist violence” and hold websites accountable for amplification of antisemitic hate, glorification of terrorism, extremism, disinformation, and incitement.”

UNSAID BUT UNDERSTOOD

Mamdani declines to support Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish state

Zohran Mamdani, a leading Democratic candidate in New York City’s June mayoral primary, declined to say whether he believes Israel has a right to exist as a Jewish state, when pressed to confirm his view during a town hall on Thursday night hosted by the UJA-Federation of New York in Manhattan, Jewish Insider’s Matthew Kassel reports.

Between the lines: “I believe Israel has a right to exist and it has a right to exist also with equal rights for all,” Mamdani said in his carefully worded response to a question posed by JI’s editor-in-chief, Josh Kraushaar, who co-moderated the event. Despite some initial resistance to addressing such questions earlier in his campaign, Mamdani, a Queens state assemblyman and a fierce critic of Israel, has in recent weeks acknowledged Israel has a right to exist. But his remarks on the matter have never recognized a Jewish state, an ambiguity he was forced to confront at the forum — where he avoided providing a direct answer.

DEFINITION DYNAMICS

Following shooting, Gottheimer urges New Jersey governor candidates to support IHRA bill

Rep. Josh Gottheimer (D-NJ), a candidate for governor of New Jersey, challenged his fellow candidates to pledge to sign bipartisan state legislation to codify the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s working definition of antisemitism in response to the murder of two Israeli Embassy officials outside the Jewish museum in Washington, Jewish Insider’s Marc Rod reports.

Background: That legislation has become a major dividing line in the gubernatorial race — Gottheimer and Rep. Mikie Sherrill (D-NJ) support it, while Jersey City Mayor Steven Fulop opposes it, but said recently he would not veto it. Other candidates did not respond to requests for comment on the issue earlier this year. Critics of the legislation say that the IHRA definition — which identifies some criticism of Israel as antisemitic — violates free speech protections. “As Governor, I’ll immediately sign New Jersey’s IHRA bill into law, and I’ll push to dismantle antisemitism and hate in any form whenever it rears its ugly head,” Gottheimer said.

EDUCATION ESCALATION

Trump escalates war on Harvard by barring all foreign students

The Trump administration on Thursday stripped Harvard University of its ability to enroll foreign students, citing Harvard’s collaboration with the Chinese Communist Party, in what the Department of Homeland Security described as an act of accountability for the university “fostering violence, antisemitism and pro-terrorist conduct from students on its campus.” The move is an escalation in President Donald Trump’s battle with Harvard, just one front in his war with elite higher education institutions. But this is the first instance of the White House completely cutting off a university’s ability to admit international students, Jewish Insider’s Gabby Deutch reports.

Israelis on campus: Harvard currently hosts more than 10,000 international students, according to university data, 160 of whom are from Israel. Current students must transfer schools or lose their visa. Harvard Hillel’s executive director, Rabbi Jason Rubenstein, expressed concern about the impact on Israeli students at Harvard. “The current, escalating federal assault against Harvard — shuttering apolitical, life-saving research; threatening the university’s tax-exempt status; and revoking all student visas, including those of Israeli students who are proud veterans of the Israel Defense Forces and forceful advocates for Israel on campus — is neither focused nor measured, and stands to substantially harm the very Jewish students and scholars it purports to protect,” Rubenstein told JI.

Worthy Reads

Today’s Blood Libel: Bari Weiss draws a line in The Free Press between anti-Israel vitriol that has pervaded protests, universities and social media in the aftermath of the Oct. 7 attacks and the murder of two Israeli Embassy staffers on Wednesday. “Venomous, untrue statements about Israel, its supporters, and the war against Hamas in Gaza chipped away at the old taboo against open antisemitism in America. Constant demonization of American Jews and Zionists is how a democratic state and its supporters have been made into targets. It is how the ‘permission structure’ for violence against Jews in America has been erected. Growing up, learning about Simon of Trent or other medieval blood libels, I wondered how something so unnatural, so deranged, could ever happen. How lies could spread so far, transmogrify into a movement, infect culture so comprehensively, and engender deadly action. … How can anyone honest with themselves not draw a connection between a culture that says Zionists are antihumans — even Nazis themselves — and the terrorists now attacking Jews across the globe?” [TheFreePress]

Israeli Resilience: Tablet’s Armin Rosen writes about the resilience of the Israeli diplomatic corps: “In my experience the diplomats of the Jewish state are among the least Israeli of Israelis. They are restrained and secular and quiet and usually know how to dress themselves; they speak with every possible accent, and it’s hard to imagine them whacking at a matkot ball, fighting their way onto a bus, or davening during halftime of a basketball game. They are the normal and cosmopolitan faces of a rambunctious and inherently tribal country. But it is the tension between the rigors of diplomacy and the character of their homeland that also makes them deeply Israeli: whatever their religious practice and whatever their politics, Israeli diplomats are inevitably Jews among the nations, a tiny sub-tribe that serves as the official foreign representation of the world’s only Jewish state, the first in 2,000 years and one of the most hated and lied-about countries in the entire history of humankind. To carry out this mission for fairly low pay on behalf of an often-dysfunctional foreign ministry, in places far from home where spies and activists and journalists and local Jews are circling you or even actively targeting you at any given moment, requires a typically Israeli mix of creativity, resourcefulness, and optimism” [Tablet]

Yaron the Healer: Mariam Wahba, a research analyst at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, eulogizes her friend Yaron Lischinsky, one of the victims of Wednesday night’s shooting outside the Capital Jewish Museum, in The Free Press. “He told me how his family lived in Israel before they moved to Germany, about moving back when he was 16, and knowing, early and without hesitation, that he wanted to be a diplomat and peacemaker. Language came easily to him: Hebrew, Japanese, English, and of course, his native German. He moved through the world with care and thoughtfulness, as if everyone and everything he touched might break. … Yaron was the kind of person who knew the exact year of the First Council of Nicaea and never made you feel small for getting it wrong. His murder leaves a wound in many hearts, one that may never fully heal, for he was the healer. Yaron was sharp, but more importantly, he was kind. He didn’t just want to understand the world. He wanted to mend it. Quietly and gently. Thoughtfully. Steadily.” [TheFreePress]

Bibi, the Bit Player: The Atlantic’s Yair Rosenberg argues that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu put too much faith in a second Trump term and has found himself sidelined from the president’s agenda. “By revealing Netanyahu to be a bit player, rather than an elite operator, Trump has not just put the Israeli leader in his place. He has exploded Netanyahu’s carefully cultivated political persona — an act as damaging to Netanyahu’s standing as the Hamas attack on October 7. Worse than making Netanyahu look foolish, Trump has made him look irrelevant. He is not Trump’s partner, but rather his mark. In Israeli parlance, the prime minister is a freier — a sucker. The third-rate pro-government propagandists on Channel 14 might not have seen this coming, but Netanyahu should have. His dark worldview is premised on the pessimistic presumption that the world will turn on the Jews if given the chance, which is why the Israeli leader has long prized hard power over diplomatic understandings. Even if Trump wasn’t such an unreliable figure, trusting him should have gone against all of Netanyahu’s instincts.” [TheAtlantic]

Word on the Street

Elias Rodriguez, the suspected gunman in the deadly shooting of two Israeli Embassy employees in Washington on Wednesday, was charged with two counts of murder and other federal crimes. Interim U.S. Attorney in Washington Jeanine Pirro said investigators are continuing to investigate the attack as a hate crime and terrorism and additional charges may be brought…

The New York Times drew parallels between Wednesday night’s killing of two Israeli Embassy employees in Washington and another murder of an Israeli diplomat in the Washington area in 1973, a case which was never solved…

Scripps News published archive footage from 2018 from an interview it conducted with Elias Rodriguez, the suspected gunman in the Wednesday night shooting of Israeli Embassy employees, during a protest in Chicago where he identified himself as a member of ANSWER Chicago. ANSWER has held protests against the Israeli war in Gaza, which the organization calls a genocide…

The shooting has stoked safety fears among Israelis and Jews amid a spike in global antisemitism, The Wall Street Journal reports…

White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said in a briefing that President Donald Trump and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu “have a good relationship, one that’s built on transparency and trust.” Leavitt said the president “has made it very clear to not just Prime Minister Netanyahu, but also the world, that he wants to see a deal with Iran struck if one can be struck.”…

The Supreme Court, in a 4-4 decision, rejected an Oklahoma Catholic school‘s bid to receive public funds as a religious charter school; the deadlocked ruling lets stand an Oklahoma Supreme Court decision barring the creation of such a charter school. The Orthodox Union had filed a brief in support of the school and said that a favorable ruling would make Jewish education more accessible…

A federal judge in Massachusetts issued a preliminary injunction blocking the Trump administration and Education Secretary Linda McMahon from dismantling the Department of Education and ordering them to reinstate department employees who had been fired. The administration said it will challenge the judge’s ruling “on an emergency basis”…

The Department of Health and Human Services’ Office for Civil Rights announced on Thursday that Columbia University violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act by “acting with deliberate indifference towards student-on-student harassment of Jewish students from October 7, 2023, through the present.” Anthony Archeval, acting director of the Office for Civil Rights at HHS, said in a statement, “We encourage Columbia University to work with us to come to an agreement that reflects meaningful changes that will truly protect Jewish students.”…

The Wall Street Journal highlights what it called the “extraordinary blurring of government negotiations and private business dealings” as Zach Witkoff, son of Middle East envoy Steve Witkoff, continues to invoke his father’s work and White House connections as he travels the world pursuing deals for his cryptocurrency venture World Liberty Financial…

Netanyahu on Thursday appointed Maj. Gen. David Zini as the next Shin Bet chief, despite a court ruling that his firing of the previous chief, Ronen Bar, and the determination of the attorney general that the move represented a conflict of interest in light of the agency’s ongoing investigation into Netanyahu’s aides’s ties to Qatar…

The Israeli airstrike that targeted Mohammed Sinwar, Hamas’ leader in Gaza, earlier this month, also reportedly killed several other high-ranking Hamas operatives as they gathered for a meeting…

Iran threatened to “implement special measures” to protect its nuclear facilities and materials if Israeli threats of a strike persist…

A failed Houthi attempt to launch a missile from the vicinity of Sana’a airport caused an explosion this morning, Muammar al-Iryani, Yemen’s information minister, said…

Globes reports that in closed meetings with Israeli officials, U.S. Ambassador to Israel Mike Huckabee conveyed concerns from Washington on several economic issues including initiatives that would affect U.S. energy giant Chevron and streaming services such as Netflix, Amazon Prime and Disney+…

Pic of the Day

Yechiel Leiter, Israel’s ambassador to the U.S. (right), on Thursday stands outside the Capital Jewish Museum in Washington, where two staff members of the Israeli Embassy were killed in a terror attack the night before. With him are (from left) Reps. Brad Schneider (D-IL), Jamie Raskin (D-MD) and Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL).

Birthdays

Actor, voice actor and stand-up comedian sometimes referred to as “Yid Vicious,” Bobby Slayton turns 70 on Sunday…

FRIDAY: Emeritus professor of physics and the history of science at Harvard, Gerald James Holton turns 103… Businessman and attorney, he acquired and rebuilt The Forge restaurant in Miami Beach, Alvin Malnik turns 92… Businessman, optometrist, inventor and philanthropist, Dr. Herbert A. Wertheim turns 86… Former dean of the Yale School of Architecture and founder of an eponymous architecture firm, Robert A. M. Stern turns 86… Founder and chairman of law firm Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, leading DC super-lobbyist but based in Denver and long-time proponent of the U.S.-Israel relationship, Norman Brownstein turns 82… British fashion retailer and promoter of tennis in Israel, he is the founder, chairman and CEO of three international clothing lines including the French Connection, Great Plains and Toast brands, Stephen Marks turns 79… Senior counsel at Cozen O’Connor, focused on election law, he was in the inaugural class of Yeshiva University’s Benjamin Cardozo School of Law, Jerry H. Goldfeder turns 78… Award-winning television writer and playwright, Stephanie Liss turns 75… Israeli diplomat, he served as Israel’s ambassador to Nigeria and as consul general of Israel to Philadelphia, Uriel Palti turns 71… Editor-in-chief of a book on end-of-life stories, she is a special events advisor to The Israel Project, Catherine Zacks Gildenhorn… Israeli businessman with holdings in real estate, construction, energy, hotels and media, Ofer Nimrodi turns 68… President of Newton, Mass.-based Liberty Companies, Andrew M. Cable turns 68… Best-selling author and journalist, whose works include “Tuesdays with Morrie,” he has sold over 42 million books, Mitch Albom turns 67… Resident scholar at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, Reuel Marc Gerecht… Chairman of the board of the Irvine, Calif.-based Ayn Rand Institute, Yaron Brook turns 64… Actor, comedian, writer, producer and musician, H. Jon Benjamin turns 59… Former ski instructor, ordained by HUC-JIR in 1998, now rabbi of the Community Synagogue of Rye (N.Y.), Daniel B. Gropper… Film and television director, Nanette Burstein turns 55… Australian cosmetics entrepreneur, now living in NYC, she is known as the “Lipstick Queen,” Poppy Cybele King turns 53… Prominent NYC matrimonial law attorney, she is the daughter of TV journalist Jeff Greenfield, Casey Greenfield turns 52… Member of the Knesset for the New Hope party, she previously served as Israel’s minister of education, Yifat Shasha-Biton turns 52… Retired attorney, now a YouTuber, David Freiheit turns 46… Executive director of the Singer Family Charitable Foundation, Dylan Tatz… Tech, cyber and disinformation reporter for Haaretz, Omer Benjakob… Professional golfer on the LPGA Tour, Morgan Pressel turns 37… Senior manager of brand and product strategy at GLG, Andrea M. Hiller Tenenboym…

SATURDAY: Co-founder of the law firm Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, he is featured in Malcolm Gladwell’s book “Outliers,” Herbert Wachtell turns 93… Professor emeritus of statistics and biomedical data science at Stanford, Bradley Efron turns 87… Biographer of religious, business and political figures, Deborah Hart Strober turns 85… Born Robert Allen Zimmerman, his Hebrew name is Shabsi Zissel, he is one of the most influential singer-songwriters of his generation, Bob Dylan turns 84… Social media and Internet marketing consultant, Israel Sushman turns 77… Member of Congress since 2007 (D-TN-9), he is Tennessee’s first Jewish congressman, Steve Cohen turns 76… Former director of planned giving at American Society for Yad Vashem, Robert Christopher Morton turns 74… Former Mexican secretary of foreign affairs, he is the author of more than a dozen books, Jorge Castañeda Gutman turns 72… President of the Israel ParaSport Center in Ramat Gan and vice chair of Birthright Israel Foundation, Lori Ann Komisar… First-ever Jewish member of the parliament in Finland, he was elected in 1979 and continues to serve, Ben Zyskowicz turns 71… Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and short story writer, Michael Chabon turns 62… U.S. ambassador to Singapore during the Obama administration, he is now the managing director and general counsel of KraneShares, David Adelman turns 61… Senior advisor at the MIT Center for Constructive Communication, Debby Goldberg… Ukrainian businessman, patron of the Jewish community in Ukraine, collector of modern and contemporary art, Gennadii Korban turns 55… Film director, in 2019 he became the second-ever Israeli to win an Academy Award, Guy Nattiv turns 52… Swedish criminal defense lawyer, author and fashion model, Jens Jacob Lapidus turns 51… Actor, who starred in the HBO original series “How to Make It in America,” Bryan Greenberg turns 47… Emmy Award-winning host of “Serving Up Science” at PBS Digital Studios, Sheril Kirshenbaum turns 45… EVP and chief of staff at The National September 11 Memorial and Museum, Benjamin E. Milakofsky… Synchronized swimmer who represented Israel at the 2004, 2008, 2012 and 2016 Summer Olympics, Anastasia Gloushkov Leventhal turns 40… Travel blogger who has visited 197 countries, Drew “Binsky” Goldberg turns 34… Member of the Iowa House of Representatives since 2023, Adam Zabner turns 26… Social media influencer and activist, Emily Austin turns 24…

SUNDAY: Academy Award-winning film producer and director, responsible for 58 major motion pictures, Irwin Winkler turns 94… Holocaust survivor as a young child, he is a professor emeritus of physics and chemistry at Brooklyn College, Micha Tomkiewicz turns 86… Co-founder of the clothing manufacturer, Calvin Klein Inc., which he formed with his childhood friend Calvin Klein, he is also a former horse racing industry executive, Barry K. Schwartz turns 83… Judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit since 1986, he is now on senior status, Douglas H. Ginsburg turns 79… British journalist, editor and author, he is a past VP of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, Alex Brummer turns 76… Of counsel in the Chicago office of Saul Ewing, Joel M. Hurwitz turns 74… Screenwriter, producer and film director, best known for his work on the “Back to the Future” franchise, Bob Gale turns 74… Los Angeles area resident, Robin Myrne Kramer… Retired CEO of Denver’s Rose Medical Center after 21 years, he is now the CEO of Velocity Healthcare Consultants, Kenneth Feiler… Israeli actress, Rachel “Chelli” Goldenberg turns 71… Professor of history at Fordham University, Doron Ben-Atar turns 68… President of the Swiss Federation of Jewish Communities, Ralph Friedländer turns 66… U.S. senator (D-MN), Amy Klobuchar turns 65… Senior government relations counsel in the D.C. office of Kelley Drye & Warren, Laurie Rubiner… Israel’s ambassador to Lithuania from 2020 until 2022, Yossi Avni-Levy turns 63… Actor, producer, director and writer, Joseph D. Reitman turns 57… Cape Town, South Africa, native, tech entrepreneur and investor, he was the original COO of PayPal and founder/CEO of Yammer, David Oliver Sacks turns 53… Member of the Australian Parliament since 2016, Julian Leeser turns 49… Former Minister of Diaspora Affairs, she is the first Haredi woman to serve as an Israeli cabinet minister, Omer Yankelevich turns 47… Senior political reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Greg Bluestein… COO at Maryland-based HealthSource Distributors, Marc D. Loeb… Comedian, actor and writer, Barry Rothbart turns 42… One of the U.S.’ first radiology extenders at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Orli Novick… Senior communications manager at Kaplan, Inc., Alison Kurtzman… Former MLB pitcher, he had two effective appearances for Team Israel at the 2017 World Baseball Classic qualifiers, Ryan Sherriff turns 35… Olympic Gold medalist in gymnastics at the 2012 and 2016 Summer Olympics, Alexandra Rose “Aly” Raisman turns 31… Laura Goldman…

Over 150 Israeli students at Harvard will be impacted by the move; they must transfer schools or lose their visas

Scott Eisen/Getty Images

An entrance gate on Harvard Yard at the Harvard University campus on June 29, 2023 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The Trump administration on Thursday stripped Harvard University of its ability to enroll foreign students, citing Harvard’s collaboration with the Chinese Communist Party, in what the Department of Homeland Security described as an act of accountability for the university “fostering violence, antisemitism and pro-terrorist conduct from students on its campus.”

The move is an escalation in President Donald Trump’s battle with Harvard, just one front in his war with elite higher education institutions. He has already revoked billions of dollars in federal funding from Harvard, as well as several other universities. Trump has also sought the deportation of hundreds of foreign students on college campuses over their alleged support for terrorism and antisemitism.

But this is the first instance of the White House completely cutting off a university’s ability to admit international students. Harvard currently hosts more than 10,000 international students, according to university data. 160 of them are from Israel. Current students must transfer schools or lose their visa.

“It is a privilege, not a right, for universities to enroll foreign students and benefit from their higher tuition payments to help pad their multibillion-dollar endowments. Harvard had plenty of opportunity to do the right thing. It refused,” Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said in a statement.

Last month, Noem asked Harvard to provide data on the disciplinary records of foreign students on campus and their record of participating in protests. Noem said the information shared by Harvard in response was “insufficient.”

Harvard Hillel’s executive director, Rabbi Jason Rubenstein, expressed concern about the impact on Israeli students at Harvard.

“The current, escalating federal assault against Harvard — shuttering apolitical, life-saving research; threatening the university’s tax-exempt status; and revoking all student visas, including those of Israeli students who are proud veterans of the Israel Defense Forces and forceful advocates for Israel on campus — is neither focused nor measured, and stands to substantially harm the very Jewish students and scholars it purports to protect,” Rubenstein told Jewish Insider.

A university spokesperson did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Barak Sella, an Israeli educator and researcher who earned a master’s degree from the Harvard Kennedy School in 2024, said the action will “be detrimental for the entire higher education system.”

“Never did any Jewish [organization] ask to ban the ability to accept foreign students, especially when a lot of the antisemitism is perpetrated by American citizens — aka the shooting last night,” Sella told JI, referring to the killing of two Israeli Embassy officials outside the Capital Jewish Museum in Washington. The alleged perpetrator is an American citizen.

Harvard is likely to take legal action in response, according to The Crimson.

Jewish Insider reporter Haley Cohen contributed to this report.

The secretary of state also assured lawmakers that all Trump administration officials are unified in their opposition to Iran maintaining domestic nuclear enrichment capabilities

BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images

Secretary of State Marco Rubio testifies before a House Subcommittee on National Security, Department of State, and Related Programs hearing on the budget for the Department of State, on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC on May 21, 2025.

In his second consecutive day of hearings on Capitol Hill, Secretary of State Marco Rubio said that he expects that additional Arab countries will join the Abraham Accords by the end of the year, if not earlier.

“We do have an Abraham Accords office that is actively working to identify a number of countries who have lined up and already I think we may have good news, certainly before the end of this year, of a number of more countries that are willing to join that alliance,” Rubio said a House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing on Wednesday.

The comments are consistent with other recent remarks by President Donald Trump and Middle East envoy Steve Witkoff.

Rubio added that the administration is currently working on selecting an ambassador for the Abraham Accords, as required under law, to submit for congressional confirmation.

He said that there is “still a willingness” in Saudi Arabia to normalize relations with Israel, but “certain conditions are impediments,” including the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas attacks on Israel and the ensuing war.

Rubio’s testimony largely reinforced and added on his comments the day before, on issues including Iran and Syria.

He again insisted that all elements of the Trump administration, including Vice President JD Vance and Witkoff, are unified behind the position that Iran cannot be allowed to maintain its capacity to enrich uranium.

And he affirmed that U.S. law requires that any deal with Iran be submitted to Congress for review and approval, noting that he had been in Congress when that law was passed.

At an afternoon hearing with the House Appropriations Committee, Rubio again said that sanctions relating to Iranian proxy terrorism or other malign activities will not be impacted by a nuclear deal that does not address those subjects. Republicans in the past have questioned the distinction between nuclear and non-nuclear sanctions, particularly as part of the original 2015 nuclear deal, which took a similar approach. And they’ve argued that any sanctions relief would allow Iran to expand its support for regional terrorism.

Rubio said the administration is continuing to ramp up sanctions on Iran, and said that European parties to the deal are “on the verge” of implementing snapback sanctions on Iran. He said that the administration would support legislation to implement additional sanctions on Iran’s oil sector.

He denied knowledge of a Tuesday leak by administration officials that Israel was making plans to strike Iran’s nuclear program, adding, “I also don’t think it’s a mystery, though … that Israel has made clear that they retain the option of action to limit Iran from ever gaining a nuclear capability.”

Expanding on comments he made the day before, Rubio said that he favors moving the mission of U.S. security coordinator for Israel and the Palestinian territories under the authority of the U.S. ambassador to Israel so that it can be a better-integrated part of the U.S.’ Israel policy. But he vowed that the core function of the office will continue.

Rubio denied reports of talks between the United States and Saudi Arabia about potential nuclear cooperation outside of a “gold standard” deal, which would include banning domestic enrichment.

The secretary of state reiterated comments about the critical necessity of providing sanctions relief to Syria to help contribute to stability, but he said that continued sanctions relief “does have to be conditioned on them continuing to live by the commitments” that the Syrian government has made verbally, including to combat extremism, prevent Syria from becoming a launchpad for attacks on Israel and form a government that represents, includes and protects ethnic and religious diversity.

He indicated that the U.S. is not actively working to shut down the United Nations Relief and Works Agency, but pledged that the United States will not be providing any further aid to or through that organization and will use its power and funding to look for alternatives.

He said it will be up to other countries whether they continue working with UNRWA, though he noted that the U.S. has been the agency’s largest donor.

Rubio said that he would be supportive, in concept, of legislation to expand current U.S. anti-boycott laws to include compulsory boycotts imposed by international organizations. That legislation was pulled from a House floor vote after right-wing lawmakers falsely claimed it would ban U.S. citizens from boycotting Israel.

Pushing back on calls for the U.S. to withhold weapons sales to the United Arab Emirates over its support for one of the parties involved in the Sudanese Civil War that the U.S. has found is committing genocide, Rubio said that the U.S. is not fully in alignment with the UAE but argued that it’s critical for the U.S. to continue engaging with and maintain a strong relationship with the UAE for its broader foreign policy goals in the Middle East.

He said that maintaining such a relationship and expanding the U.S.’ diplomatic and economic relationship with Abraham Accords countries is also important to ensuring that the Accords continue to be successful.

Rubio said that the State Department had approved restarting aid programs for Jordan that remained frozen — though he noted most were initially exempted from the administration’s blanket freeze. He acknowledged that the frozen programs had been “a source of frustration for [Jordan], and frankly for me.” He continued, “Ultimately, we’re going to get all those programs online, if they’re not online already.”

In a heated back-and-forth with Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA), who was brandishing a pocket Constitution, Rubio again defended the administration’s policy of revoking student visas from individuals accused of involvement in anti-Israel activity on college campuses, saying that they are coming to the United States to “tear this country [apart]” and “stir up problems on our campuses.”

Addressing the case of Rümeysa Öztürk, a Tufts University graduate student that supporters have said was detained solely for writing an op-ed in a student newspaper criticizing Israel, Rubio claimed the situation is not as has been represented. “Those are her lawyers’ claims and your claims, those are not the facts,” Rubio said.

Asked by Jayapal about a comment — “Jews are untrustworthy and a dangerous group” — made by an Afrikaner refugee recently admitted to the United States from South Africa, Rubio said that he would “look forward to revoking the visas of any lunatics you can identify.”

But when presented with the fact that the individual in question was admitted as a refugee, not on a visa, Rubio said that refugee admissions are “a totally different process,” adding “student visas are a privilege.”

Altfield succeeds Maury Litwack, who founded the coalition to advocate for government funding of Jewish schools

Courtesy

Sydney Altfield (left), Director of State Operations of New York State Kathryn Garcia and New York Gov. Kathy Hochul.

Sydney Altfield, a champion of STEM education, has been tapped as national director of Teach Coalition, an Orthodox Union-run organization that advocates for government funding and resources for yeshivas and Jewish day schools, Jewish Insider has learned. She succeeds Maury Litwack, who founded the coalition in 2013 and served as its national director since.

Altfield, who has held various roles with Teach Coalition for the past seven years, most recently served as executive director of its New York state chapter. In that position, she spearheaded STEM funding for private schools in the state and helped establish state security funding programs — two areas she intends to expand on a national level in the new role, which encompasses seven states: New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Florida, Pennsylvania, California and Nevada.

“We’re at a very pivotal moment in Jewish day schools where the continuity of the Jewish people relies on Jewish education and having access to such. That also has to come at a quality education,” Altfield told JI in her first interview since being selected for the position. “It’s so important to understand that it’s not just about STEM but it’s about the entire Jewish education being high quality, something that’s accessible for everyone.”

Amid rising concerns about security in Jewish schools, Altfield said she looks forward to taking “the wins we’ve had in places like Florida,” referring to universal tax credit scholarships, to ensure that funds are effectively used to protect Jewish students and staff.

Soon after the Oct. 7, 2023, terrorist attacks, Teach Coalition launched Project Protect to write and implement federal- and state-level security grants.

“A lot of people thought that after Oct. 7 the rise in hate crimes and antisemitism, and specifically the rise in security threats, would go down but we’re seeing just the opposite,” Altfield said. “It’s very important for us to realize what is ahead and what is needed … to ensure that the financial burden of an antisemitism tax is halted as soon as possible.”

According to a Teach Coalition survey published in April, security spending among 63 of the coalition’s member schools in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Florida increased a staggering 84% for the 2024-2025 school year, with these schools now spending $360 per student more on security than before Oct. 7. The costs ultimately get passed on to families in the form of security fees or increased tuition.

Altfield credits herself with building “very strong” multifaith coalitions while overseeing the New York chapter.

“I feel that New York is just scratching the surface,” she told JI. “I really do believe that our struggles as a Jewish community in ensuring a quality Jewish education is the same when it comes to Islamic education or Catholic schools, and if we have a united voice we can work together and move the needle faster. It makes our voice that much louder.”

Under Litwack’s leadership, Teach Coalition ran several successful voter mobilization initiatives in Westchester and Long Island elections. Altfield said that while she plans to work with Litwack on some initiatives, “Teach will be going back to the basics of quality, affordable education.”

Meanwhile, “there’s a new wave of needing a Jewish voting voice across the nation,” Altfield said, noting that the transition will allow Litwack to continue that effort in a separate organization he has formed, Jewish Voters Unite.

“It has been a privilege founding and building Teach Coalition into the powerhouse organization that it is today,” Litwack told JI. “I’ve had the privilege of working alongside Sydney for years — someone whose vision, integrity, and dedication have helped shape what the organization has become.”

“The Orthodox Union community — along with other faith communities — is committed to educate its students in our day schools and yeshiva, where their faith and values are nurtured while they receive a well-rounded education. Especially as our community faces record antisemitism, that high-quality Jewish education needs to be made more accessible,” Rabbi Moshe Hauer, executive vice president of the Orthodox Union, said in a statement, adding that Altfield’s promotion “represents the redoubling of our commitment to helping Jewish Day School and Yeshiva families and those that aspire to attend these schools.”

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul and New York City Mayor Eric Adams also took note of the work Altfield has done locally. “Governor Hochul has forged a close partnership with Teach NYS throughout years of advocacy and collaboration, continuing this administration’s ironclad commitment to fighting antisemitism and supporting Jewish New Yorkers,” a spokesperson for Hochul said in a statement.

“Sydney is a true bridge-builder and her leadership at Teach NYS helped deliver real results for our families,” Adams said.

Altfield said she takes the helm of the organization at a time when it is “becoming even more important and more visible” than ever.

On a federal level, for instance, “it’s very interesting to see where the Trump administration is going when it comes to education funding,” she said.

“They are very supportive of educational freedom and choice and that’s what we’re about so we’re very excited to see the changes that are coming, whether that be through the administration or even through a federal tax credit program that’s currently being discussed in Congress,” Altfield continued.

Last week, the topic of Jewish education was brought to an international stage when podcast host and author Dan Senor said that Jewish day schools are one of the strongest contributors of a strong Jewish identity — one that provides the tools that are needed at this precarious moment to “rebuild American Jewish life” — as he delivered the 45th annual State of World Jewry address at the 92NY.

“I’ve been saying this for so long and Dan gets the credit for it — as he should,” Altfield said with a laugh.

“People always ask me why I do what I do,” she continued. “Even before Oct. 7, I said I believe that the continuity of the Jewish people lies within Jewish education. You cannot stress that any more than what has been seen after Oct. 7.”

Altfield pointed to increased enrollment in Jewish day schools nationwide. “A lot of what the Jewish community is going through is under a microscope,” she said. “Now that microscope is blowing up the understanding that Jewish education is basically the savior of what’s going to help us through these next few years.”

Plus, Israel prepares for Edan Alexander's release

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

President Donald Trump gestures as he departs Air Force One at Miami International Airport on February 19, 2025 in Miami, Florida.

Good Monday morning.

In today’s Daily Kickoff, we look at the state of relations between Washington and Jerusalem ahead of President Donald Trump’s trip to Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates this week, and report on how Capitol Hill is reacting to Qatar’s plans to gift a $400 million luxury jet to Trump. We also do a deep dive into the ‘123 Agreement’ being pushed by GOP senators wary of nuclear negotiations with Iran, and report on the University of Washington’s handling of recent anti-Israel campus protests. Also in today’s Daily Kickoff: Iris Haim, Natalie Portman and Nafea Bshara.

What We’re Watching

- Middle East envoy Steve Witkoff is in Israel today following the announcement that Hamas will release Israeli American hostage Edan Alexander today. Adam Boehler, the administration’s hostage affairs envoy, arrived in Israel earlier today along with Alexander’s mother, Yael. More below.

- President Donald Trump is departing later today for his three-country visit to the Middle East. More below.

- An Israeli delegation will reportedly travel to Cairo today to renew negotiations with Hamas.

- Israeli President Isaac Herzog is in Germany today, where he is marking 60 years of German-Israeli relations.

- This afternoon in Tel Aviv, hostage families will march from Hostage Square to the U.S. Embassy Branch Office to call for a “comprehensive” agreement to free the remaining 59 hostages.

What You Should Know

A QUICK WORD WITH Melissa Weiss

“Donald, Bring Them Home” reads a sign in the window of a clothing boutique on Tel Aviv’s busy Dizengoff Street. It’s been in the store window since January, when a temporary ceasefire freed dozens of Israeli hostages, including two Americans, who had been held in captivity in Gaza for over a year. It’s a smaller sign than the billboard that read “Thank you, Mr. President” and for weeks was visible to the thousands of motorists driving on the busy thoroughfare next to the beach.

Returned hostages and hostage families have appealed to the Trump administration for assistance in securing their loved ones’ releases, expressing sentiments conspicuously absent in meetings between former hostages and Israeli government officials, including Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. It’s a situation that underscores how the American efforts to secure the release of the remaining hostages have at times been done not only without Israeli buy-in, but with Israel finding out only after the negotiations concluded.

Such was the case yesterday, when Trump announced that Edan Alexander, the last living American hostage in Gaza, would be released.

The negotiations over the release of Alexander underscore the Trump administration’s “America First” approach to the region that has sidelined Israeli priorities on a range of issues, from the Houthis to Iran to the war in Gaza. It’s a splash of cold water in the face of a nation that largely celebrated Trump’s election six months ago.

The announcement of Alexander’s expected release came after a firehose of news in the days leading up to Trump’s visit to the Middle East, which begins tomorrow. First, the move toward allowing Saudi Arabia to have a civilian nuclear program. Then, the news, confirmed on Sunday by Trump, that Qatar is gifting the president a luxury plane to add to the Air Force One fleet, amid yearslong Boeing manufacturing delays. (More below.)

The Qatari gift alarmed Washington Democrats, with Rep. Ritchie Torres (D-NY) writing to Trump administration officials to express “alarm,” saying Qatar has a “deeply troubling history of financing a barbaric terrorist organization that has the blood of Americans on its hands. In the cruelest irony, Air Force One will have something in common with Hamas: paid for by Qatar.”

Only hours after the news of the gifted jet broke, Trump announced that the U.S., along with Egyptian and Qatari mediators, had reached an agreement to secure Alexander’s release, which he referred to as “the first of those final steps necessary to end this brutal conflict.” Israel was not mentioned a single time in the announcement.

Netanyahu himself conceded that the Americans had reached the deal absent Israeli involvement. “The U.S. has informed Israel of Hamas’s intention to release soldier Edan Alexander as a gesture to the Americans, without conditions or anything in exchange,” Netanyahu said on Sunday evening.

The news stunned observers and offered a measure of renewed hope to the families of remaining hostages, including the four Americans whose bodies remain in Gaza, but opened a deluge of questions about the diplomatic dance that led to an agreement over Alexander’s release.

The timing of the announcement – shortly after news of the gifted Qatari jet broke — raised questions about the potentially transactional nature of the discussions, and deepened concerns that the Trump administration could reach agreements that run counter to Israeli security priorities while the president travels the region (a trip that does not include a stop in Israel, despite Netanyahu’s two visits to the White House since Trump returned to office).

As Trump travels to Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates this week, the world will be watching closely. But perhaps nobody will be watching as closely — from more than 1,000 miles away — as Netanyahu.

FIRM FRIENDS?

Trump, Netanyahu administrations downplay rift despite disagreements on Iran, Saudi Arabia

The headlines in the Hebrew media, on the eve of President Donald Trump’s visit to the Middle East this week, played up what some see as an emerging rift between Israel and the U.S. “Concerns in Israel: The deals will hurt the qualitative [military] edge,” read one. The Trump administration has already made a truce with the Houthis and cut a deal with Hamas to release Israeli American hostage Edan Alexander — without Israel — and the concern in Jerusalem is that more surprises — good and bad — may be on the way. Yet insiders in both the Trump administration and the Netanyahu government speaking to Jewish Insider’s Lahav Harkov in recent days on condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive matters took a more sanguine view of the delicate diplomacy, saying that there is no rift, even if there are disagreements.

Calm but critical: Sources in Jerusalem pointed to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s two visits to the White House in Trump’s first 100 days in office, as well as Israeli Strategic Affairs Minister Ron Dermer’s meeting with the president last week. A Trump administration source said the relationship remains positive and close, but also criticized Israel for not adapting to the president’s transactional approach to foreign policy. Gulf states are likely to announce major investments in the U.S. during Trump’s visit, while Israel has largely been asking the administration for help. Jerusalem could be putting a greater emphasis on jobs created by U.S.-Israel cooperation in the defense and technological sectors when they speak with Trump, the source suggested.

Signs of stress: The apparent divisions are especially notable in the context of the Iran talks — Israel largely opposes diplomacy with the regime and favors a military option to address Iran’s nuclear program, on which the Trump administration has not yet been willing to cooperate, Jewish Insider’s Marc Rod reports.

GIFT OR GRIFT?

Congressional Democrats outraged by reports of Qatari Air Force One gift

Congressional Democrats are expressing outrage over reports that the Qatari government plans to give to President Donald Trump a luxury jet for use as Air Force One, which would reportedly continue to be available for Trump’s use after his presidency, and transferred to his presidential library, Jewish Insider’s Marc Rod reports.

What they’re saying: Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) said that accepting the jet would be “not just bribery, it’s premium foreign influence with extra legroom.” Rep. Ritchie Torres (D-NY) wrote to Trump administration officials to express “alarm,” calling the reported gift a “flying grift.” Torres condemned Attorney General Pam Bondi — who previously served as a lobbyist for Qatar — for approving the reported transfer, which Torres said “flagrantly violates both the letter and the spirit of the Constitution’s Emoluments Clause.” Some conservatives, including far-right influencer Laura Loomer, Rep. Warren Davidson (R-OH) and commentator Mark Levin, are also expressing concern.

Read the full story here with additional comments from Sens. Chris Murphy (D-CT) and Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-MD).

The ABCs of 123s

U.S., Iran are talking about a ‘123 Agreement.’ What does that mean?

Last week, a group of Senate Republicans introduced a resolution laying down stringent expectations for a nuclear deal with Iran. One of those conditions is a so-called “123 Agreement” with the United States, after “the complete dismantlement and destruction of [Iran’s] entire nuclear program,” Jewish Insider’s Marc Rod reports.

What it means: A source familiar with the state of the talks confirmed to JI that a 123 Agreement is a key part of the ongoing U.S.-Iran talks currently being led by U.S. Middle East envoy Steve Witkoff, though a Witkoff spokesperson said “The sources don’t know what they’re talking about.” Those agreements refer to Section 123 of the U.S. Atomic Energy Act, which lays out conditions for peaceful nuclear cooperation between the United States and other countries. Twenty-five such agreements are currently in place — but in most cases they pertain to U.S. allies and partners. A 123 Agreement was not part of the original 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action — they are only required in cases in which the U.S. is going to be sharing nuclear material or technology with a foreign country, directly or indirectly. The prospect of inking such a deal with Iran is meeting with surprise and heavy skepticism from experts.

DEM DIVIDE

Over half of Senate Democrats blast Israel’s Gaza operations plan

A group of 25 Senate Democrats, comprising more than half of the caucus and led by several senior leaders, wrote to President Donald Trump on Friday condemning new plans for expanded Israeli military operations in the Gaza strip and accusing the Trump administration of failing to push for peace, Jewish Insider’s Marc Rod reports. Signatories include top lawmakers on some key Senate committees and senior members of the Democratic caucus.

What they said: “This is a dangerous inflection point for Israel and the region, and while we support ongoing efforts to eliminate Hamas, a full-scale reoccupation of Gaza would be a critical strategic mistake,” the lawmakers said, of Israel’s plan to expand military operations in Gaza. They also rejected a new plan for aid distribution in Gaza, which they described as an Israeli plan but which U.S. officials have described as American-led.

Hostage hopes: A bipartisan group of 50 House members wrote to President Donald Trump on Friday urging him to “prioritize the release of the five Americans” who remain hostage in Gaza.

Q&A

Mother of hostage killed in friendly fire: ‘I choose not to blame anyone’

Most of the best-known hostage relatives in Israel are those who have led demonstrations and called to topple the government. But Iris Haim became renowned in Israel for taking a radically different approach. Haim’s son, Yotam, was kidnapped by Palestinian terrorists on Oct. 7, 2023. He and fellow hostages Samar Talalka and Alon Shimriz managed to escape captivity, only to be mistakenly killed by the IDF on Dec. 15, 2023. Yet days after Yotam was killed, rather than express anger or even anguish, Haim chose to send a message of forgiveness and encouragement to the troops. Since then, Haim has been lauded by many Israelis, even granted the honor of lighting a torch at Israel’s official Independence Day ceremony last year. Jewish Insider’s Lahav interviewed Haim at the Global Network for Jewish Women Entrepreneurs and Leaders’ 2025 Global Leadership Conference last week.

Haim’s philosophy: “I’m not avoiding life, but I’m choosing how to deal with it … I don’t blame anybody, because I don’t believe in that way … I have my philosophy of life. Life can be good for me. It all depends on me. I can find so much good, and I need to choose to see it. It depends on where we put our focus,” Haim told JI. “There is also a lot of bad. Yesterday we heard about two more soldiers who were killed … I cannot control this. What I cannot control, I’m not dealing with. I can’t change what [Israeli Prime Minister] Bibi [Netanyahu] thinks or what this government is doing. I can only vote differently next time, and that’s the way to keep myself normal and not go crazy.”

NEW DIRECTION

UW changes tack on anti-Israel activity, suspends students involved in destructive protest

The University of Washington suspended 21 students who were arrested during anti-Israel protests at the Seattle campus earlier this week, according to the university, a marked shift from the school’s reaction to previous anti-Israel activity, Jewish Insider’s Danielle Cohen and Haley Cohen report. The suspended students, who are also now banned from all UW campuses, were among more than 30 demonstrators, including non-students, arrested for occupying the university’s engineering building on Monday night — causing more than $1 million worth of damage. Masked demonstrators blocked entrances and exits to the building and ignited fires in two dumpsters on a street outside. Police moved into the building around 11 p.m.

University response: After Monday’s events, the university’s president, Ana Mari Cauce, quickly denounced the “dangerous, violent and illegal building occupation and related vandalism” and condemned “in the strongest terms the group’s statement celebrating the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas terrorist attacks against Israeli civilians.” Miriam Weingarten, co-director of Chabad UW with her husband Rabbi Mendel Weingarten, expressed gratitude to the school for its swift response to the latest incident, which she called “appalling and horrific.”

On the East Coast: Columbia University suspended more than five dozen students in connection with last week’s protest at the school’s main library; 33 other individuals were barred from the New York City campus over the incident.

Worthy Reads

Show of Force: Former Wall Street Journal publisher Karen Elliott House suggests that the U.S. and Israel mount a joint strike on Iranian nuclear facilities. “The only honorable option is to dismantle it. This can be done through diplomacy, which is highly unlikely, or with force. Any other outcome endangers both Israel and Saudi Arabia, key U.S. partners in the Middle East, and destroys Mr. Trump’s credibility with the world. The president adamantly — and repeatedly — has insisted he will accept nothing less than ‘total dismantlement’ of Iran’s nuclear program. The mullahs in Tehran will never agree to that. They saw what happened to Ukraine and Libya after giving up their nuclear ambitions. They think that enriching uranium for their nuclear reactors is a national right. Their real goal isn’t electricity generation but the ability to produce material for a bomb. … Destroying Iran’s nuclear capability involves risks, and Mr. Trump wants to avoid war. But if he believes Iran can be trusted to execute a new pact, he hasn’t done his homework.” [WSJ]

Altman’s Ascent: The Financial Times’ Roula Khalaf interviews OpenAI CEO Sam Altman in his California home about his rise in the tech industry and future plans for the AI company. “As we talk, I search for clues in his upbringing that hint at his future stardom. He says there are none. ‘I was like a kind of nerdy Jewish kid in the Midwest . . . So technology was just not a thing. Like being into computers was sort of, like, unusual. And I certainly never could have imagined that I would have ended up working on this technology in such a way. I still feel sort of surreal that that happened.’ The eldest of the four children of a dermatologist mother and a father who worked in real estate, Altman read a lot of science-fiction books, watched Star Trek and liked computers. In 2005, he dropped out of Stanford University before graduating to launch a social networking start-up. In those days, AI was still in its infancy: ‘We could show a system a thousand images of cats, and a thousand images of dogs, and then it [the AI] could correctly classify them, and that was, like, you were living the high life.’” [FT]

Word on the Street

A senior U.S. official said that American negotiators were “encouraged” by the fourth round of nuclear talks with Iran, held yesterday in Oman…

Members of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum board clashed over the decision by the Trump administration to remove several board members appointed by former President Joe Biden, including former Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff and former White House Chief of Staff Ron Klain…

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) ruled out a Senate bid to challenge Sen. Jon Ossoff (D-GA), further narrowing the GOP field days after Gov. Brian Kemp announced he would not enter the Senate race; Rep. Buddy Carter (R-GA) became the first Republican to enter the race last week…

Rep. Randy Fine (R-FL) and Sen. Rick Scott (R-FL) introduced legislation to specifically ban religious discrimination under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, a prospect that has been discussed on the Hill for several years to combat antisemitism on college campuses…

Rep. Michael Baumgartner (R-WA) introduced a resolution condemning Iran’s failure to fulfill its Nonproliferation Treaty obligations and comply with International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors, and supporting military force against Iran if it withdraws from the NPT or crosses the nuclear threshold…

Reps. Jerry Nadler (D-NY), Adam Smith (D-WA) and Jim Himes (D-CT) introduced legislation providing for sanctions on individuals involved in enabling violence or destabilizing activity in the West Bank, including government officials. The legislation echoes sanctions in place under the Biden administration…

A federal program that provides funding to help vulnerable nonprofits meet their security needs has again begun reimbursing recipients, after a funding freeze at the Federal Emergency Management Agency left the fate of the Nonprofit Security Grant Program in limbo, Jewish Insider’s Marc Rod and Gabby Deutch report…

As University of Michigan President Santa Ono is set to become president at University of Florida, he said on Thursday that “combating antisemitism” will remain a priority, as it has “throughout my career,” Jewish Insider’s Haley Cohen reports…

Rümeysa Öztürk, the Turkish student at Tufts University who was arrested in March and held in a detention center as she appealed the Trump administration’s deportation efforts, was released following a federal judge’s order…

The New York Times’ Jodi Rudoren reflects on her experiences saying Kaddish, the mourner’s prayer, after her father’s death…

The Wall Street Journal looks at the relationship between Amazon Web Services and Nafea Bshara’s Annapurna Labs, which “has become essential to the success of the whole company” since AWS purchased the startup, which was founded in Israel, a decade ago in a $350 million deal…

Actress Natalie Portman is slated to star in Tom Hooper’s “Photograph 51,” a biopic about British scientist Rosalind Franklin…

The Washington Post spotlights a WWII battalion comprised of first-generation Japanese American soldiers who played a role in the liberation of Dachau…

The Associated Press looks at a Dutch-led effort to digitize roughly 100,000 records from the Jewish community of Suriname, dating back to the 18th century…

U.K. Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson warned that antisemitism among British youth is experiencing a “horrific surge” and becoming a “national emergency”…

The Wall Street Journal reports on the sexual assault allegations made against Karim Khan, the International Criminal Court’s chief prosecutor, shortly before he announced his pursuit of arrest warrants for senior Israeli officials…

The IDF and Mossad recovered the remains of Sgt. First Class Zvi Feldman, who went missing along with two other soldiers during a battle in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley during the First Lebanon War in 1982; a joint IDF-Mossad statement said that Feldman’s remains were recovered “from the heart of Syria” in a “complex and covert operation” that used “precise intelligence”…

Israel issued an evacuation warning for the Yemeni ports of Ras Isa, Hodeidah and Salif, days after carrying out strikes at the Sana’a airport targeting the Iran-backed Houthis…’

The Houthis fired a ballistic missile toward Israel on Monday morning; the missile fell short and landed in Saudi Arabia…

In his first Sunday address since being selected as pontiff, Pope Leo XIV called for a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas war, the distribution of aid to Gaza and “all hostages be freed”…

Rob Silvers, the under secretary for policy at the Department of Homeland Security during the Biden administration, is joining Ropes & Gray as a partner, and will co-chair the firm’s national security practice…

Heavy metal band Disturbed frontman David Draiman is engaged following his proposal to model Sarah Uli at a show in Sacramento over the weekend…

Holocaust survivor Margot Friedländer, who returned in 2010 to live in Berlin, where she shared her story of survival with German audiences, died at 103…

Pic of the Day

Former hostage Emily Damari, visiting London on Sunday, attended her first Tottenham game since being released. Ahead of the game, Damari and her mother, Mandy Damari, met with supporters and called for the release of her friends Gali and Ziv Berman, twin brothers who were taken, alongside Damari, from Kibbutz Kfar Aza on Oct. 7, 2023, and remain in captivity.

Birthdays

Haifa-born actress and model, she is known for her lead roles in seven films since 2014, Odeya Rush turns 28…

Israeli agribusiness entrepreneur and real estate investor, he was chairman and owner of Carmel Agrexco, Gideon Bickel turns 81… World-renowned architect and master planner for the World Trade Center site in Lower Manhattan, he also designed the Jewish Museum in Berlin, Germany, Daniel Libeskind turns 79… Former member of the California state Senate for eight years, following six years as a member of the California Assembly, Lois Wolk turns 79… Chairman of the Israel Paralympic Committee, he served for four years as a member of the Knesset for the Yisrael Beiteinu party, Moshe “Mutz” Matalon turns 72… Former Washington correspondent for McClatchy and then the Miami Herald covering the Pentagon, James Martin Rosen turns 70… SVP and deputy general counsel at Delta Air Lines until 2024, now chief legal officer at private aviation firm Wheels Up, Matthew Knopf turns 69… Professor at Emory University School of Law, he has published over 200 articles on law, religion and Jewish law, Michael Jay Broyde turns 61… Actress known for her role as Lexi Sterling on “Melrose Place,” she also had the lead role in many Lifetime movies, Jamie Michelle Luner turns 54… Founder of strategic communications and consulting firm Hiltzik Strategies, Matthew Hiltzik turns 53… Communications officer in the D.C. office of Open Society Foundations until earlier this month, Jonathan E. Kaplan… First-ever Jewish governor of Colorado, he was a successful serial entrepreneur before entering politics, Jared Polis turns 50… Professor of mathematics at Bar-Ilan University and a scientific advisor at the Y-Data school of data science in Israel, Elena Bunina turns 49… Italian politician, she is the first-ever Jewish mayor of Florence, Sara Funaro turns 49… Israeli pastry chef and parenting counselor, she is married to former Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, Gilat Ethel Bennett turns 48… Author, blogger and public speaker, Michael Ellsberg turns 48… Senior advisor at Accelerator for America Action, Joshua Cohen… Technology and social media reporter at Bloomberg, Alexandra Sophie Levine… Senior director of government affairs at BridgeBio, Amanda Schechter Malakoff… Civics outreach manager at Google, Erica Arbetter…

The antisemitism report included commitments to partner with an Israeli university, host an annual antisemitism symposium and release a yearly report on the university’s response to Title VI complaints

Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images

Harvard Yard during finals week, December 13, 2023 in Cambridge, Mass.

Harvard University’s long-awaited dual reports on antisemitism and Islamophobia, released on Tuesday, reveal a campus beset by tension and simmering distrust — as well as a university struggling to handle competing claims of discrimination, animosity and exclusion made by Jewish and Muslim students.