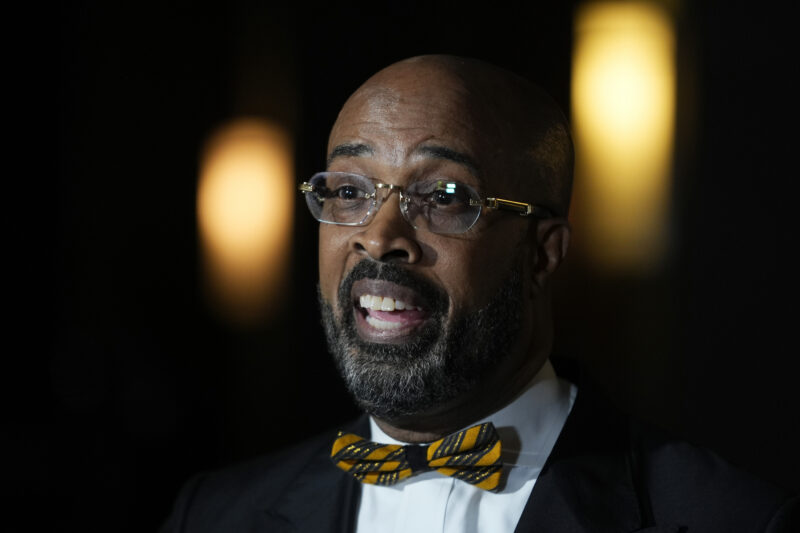

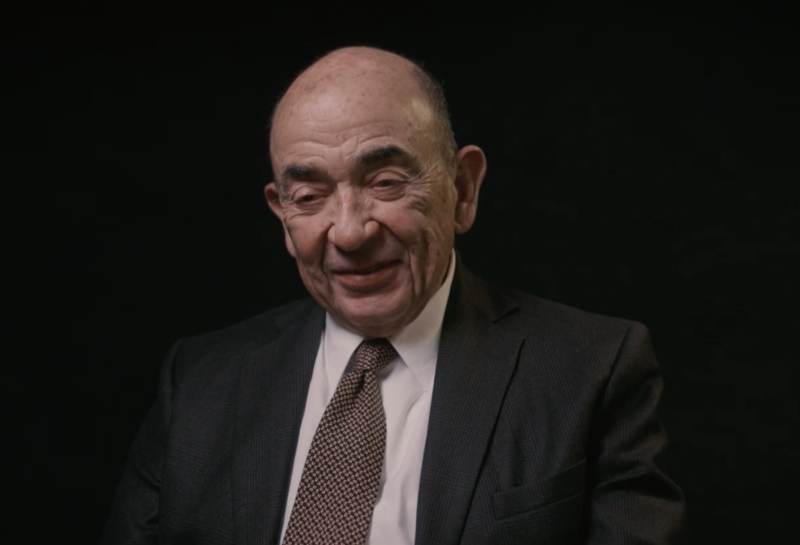

Jack Lew on Shabbat during White House years

Alex Wong/Getty Images

Secretary of the Treasury Jacob Lew listens as he participates in a discussion during the second annual Financial Inclusion Forum December 1, 2016, at The Ronald Reagan Building & International Trade Center in Washington, D.C.

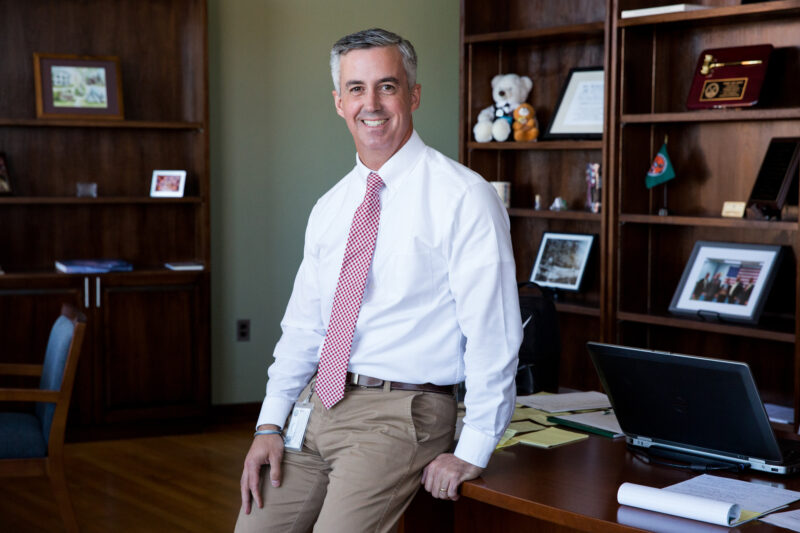

HEARD LAST NIGHT — at Columbia University’s Institute for Israel and Jewish Studies: Former Treasury Secretary Jack Lew recalled his experience working with former House Speaker Tip O’Neill, President Bill Clinton, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and President Barack Obama (including his time as White House Chief of Staff), in a conversation moderated by Foreign Policy Fellow Daniel Bonner.

Lew on being an observant Jew serving at the highest levels of government: “I have worked for some of the most powerful constitutional officers in the country and I’ve only been treated with respect and it has been in no way an obstacle to my advancement and to my performance. If it had been an obstacle to my performance, it would have been an obstacle to my advancement. It’s like any other profession where things sometimes come up that are challenging because of observing Shabbat and Yom Tov… To me, the challenge was not finding a decisional structure where I felt I could do it with an observant lifestyle. To me, the challenge was being honest with myself — over when I really needed to be there and when I didn’t.”

On his tenure as Obama’s chief of staff: “He knew me pretty well… He said, “You know this is a 24/7 world, you’ve worked in every important part of it, and you’re going to be the one who has to decide when it is something that you need to be here for on a Friday night or Saturday. It won’t stop – but you’ve figured it out before and you’ll figure it out now. I’ll never be the one who says, ‘You need to be here,’ so you better make sure you don’t forget where your line is.” There were more Saturdays that I was in the office as Chief of Staff than any other year. I lived within walking distance. I could walk in — usually go to shul and then walk in — and it wasn’t always the most pleasant way to spend Shabbat, to walk into a meeting where people are yelling at each other over a budget agreement… but, fundamentally, if you are prepared to let things go on without you, it [working on Shabbat] doesn’t happen anywhere near every week…

There are periods of time when it becomes necessary to be there. Frankly, it was harder to be a deputy than to be more senior. Because when you’re a deputy, in some ways, you’re the connective tissue. When I was deputy director of OMB, and we were doing the balanced budget agreement in 1997, all the loose threads were in my head. if I wasn’t there, people didn’t know what everybody else knew. I was the field coordinator of this complicated, multipart negotiation. and when I was OMB Director, all the players would say, “isn’t it time for you to leave?” and then they’d break for Friday night. So — to some extent — when you get a little bit more senior, or a lot more senior, some of the schedule works around you. But not all of it- when the president was running for re-election in 2012, some weeks the only day he was in the building was Saturday. I’d know in advance, and go and sit in the Roosevelt Room or in the Oval Office and spend a couple of hours catching up, talking, doing what we had to do, and then I’d go home.

Lew also sought to set the record straight on a story about Clinton calling him on Shabbat while he served as OMB director: “There’s an apocryphal story, and I’ve spent considerable effort trying to push back on it, that President Clinton once called me, ostensibly couldn’t reach me and was unhappy about it… It could not be further from the truth. What actually happened was – this was the days before all the fancy messaging systems – I came home from shul on a Saturday morning, and the telephone is taking a message from the White House switchboard, and it is saying, ‘Please disregard the message that President Clinton left, he doesn’t want to bother you. He just realized it is still Saturday [Shabbat] in Maryland… this is not important… you can forget about it.’ That’s the real story… The truth of the matter is it reflects the kind of openness, generosity of spirit, that I experienced with President Clinton, President Obama, Speaker O’Neill, Secretary Clinton. It was never an issue… in an emergency, they all knew how to reach me, and no one ever doubted that they could. And they also knew that in an emergency it wasn’t going to be hard to get me to be where I needed to be…if somebody’s life was on the line, I wasn’t going to take any more time to think about it than a doctor would.”

On the U.S.-Israel relationship under Obama: “Leave aside, for the moment, a personal relationship. The relationship between the United States and Israel was extremely close for the eight years, whether it was military, intelligence, or economic cooperation, everything was at the highest level they’d ever been. There was a global effort starting with the Goldstone Report and cropping up on a regular basis to isolate Israel. And the United States was really the only country that was out there under President Obama defending Israel against things like the Goldstone Report. I can’t tell you how many dozens of phone calls were made, presidential, vice presidential, secretarial, sub-cabinet level, to try and prevent Israel from being isolated. There were differences on policy, and I think the differences are legitimate differences. But I agreed with President Obama – and do – on issues like the settlements policy. I think that if one cares deeply about a stable, lasting, peaceful future for Israel, preserving space for there to be a negotiated two-state solution is critical. And I think unilateral actions that make that less likely to happen also diminish the probability of a long-term stable, secure future.”

“The personal dynamic between the President and the Prime Minister was not as good as one might have hoped. And it was in both directions. I mean I saw as much provocation coming from the Prime Minister… I saw more provocation coming in than I saw going out. Now, you can say that the President should ignore that and it shouldn’t make a difference, and usually it didn’t. But some things like the [2015] speech to a joint session of Congress, kind of went beyond the pale of what you can just ignore. I think that was a huge mistake for Israel. A, it wasn’t going to work, B, it contributed to a trend of Israel identifying on a partisan basis when for most of 70 years there was no question that both parties could be pro-Israel. I don’t think that there was a personal relationship that stood in the way of the bilateral relations between our countries. I don’t think that there was anything about the personal relationship that weakened US support for Israel. When the Iron Dome needed to be completed and funded, we were there in a heartbeat. When there were any questions about threats, information was shared and I think if you talk to intelligence and military officials in Israel, they freely acknowledge that the relationship had never been better. So I think it is important to separate out the signal and the noise.”

On the Obama admin. UNSC move last December: “It wasn’t the U.S. choice for this issue to be in the UN for a vote. Interestingly, the countries that had worked to create the lead-up to the resolution, you know Egypt and UK, and U.S. involvement was, to take out of the resolution, the most offensive elements of it. In the end the decision whether to veto or not is always a hard one. When you’ve used your potential veto to improve a resolution and in the form its in at the end it reflects positions that you’ve taken, to veto it is very difficult. I certainly could make the case either way, but I think it’s not been fairly characterized in a lot of the debate in the community. And afterwards the pressure was brought on some of the parties that were brought into a place where it was ultimately going to be voted on. Perhaps the effort should have been put into preventing it from being presented. I don’t think it’s a great thing for Israel to always have only the United States standing between it and condemnation. And if the United States can play a role in addressing the things that are most offensive and improving what it is the world votes on, that’s actually helpful in the long run. Personally, I wish the resolution hadn’t been there at all. I’m not happy that there was a resolution. I’m also happy it wasn’t in its original form where we would have had to veto it, but then the rest of the world would have been voting for this even harsher condemnation. When it comes down to whether or not you think that settlements are appropriate and legal, you’ve said that for seven years and you know 11 months, that you don’t think they are. It’s hard to veto it over that issue. It doesn’t mean you’re not a friend of Israel. And it doesn’t mean that after that resolution you stop being a friend of Israel. The attempts to change the outcome – I don’t think they will survive historical review favorably.”

On Trump’s Jerusalem move: “On the one hand, since the founding of Israel – as a practical matter – American presidents and cabinet officials have been out to Jerusalem and met with the prime minister and leaders of the government, and treated Jerusalem as if it were the capital. But by the same token, presidents of both parties have not taken the step of unilaterally making the decision to declare to be the capital, or move the embassy. Now you can say that’s a legal fiction. Legal fictions are not without their merit. We have a lot of legal fictions in our tradition that help us to cope with difficult issues. I think that if the purpose of the legal fiction is to preserve the possibility of having a negotiated agreement that will produce ultimately some day a just and lasting peace with two states, that is the higher value. Congress passed this legislation and president after president had the unpleasant task of having to sign a waiver. We now have a president who doesn’t like to make those signatures. And you know, there’s a pattern that’s developed that it just rankles him to have to sign those waivers. I hope that this turns out not to be a major disruption. It’s a little hard to tell because it’s so fresh. But you know, if you care, as I do, about having permanent security for a democratic state of Israel, there is no pathway other than a two state solution. The more you hear talk about a one state solution, the more it means it’s not a democratic state. That is not the Israel that I want for my grandchildren to love.”

On the Iran nuclear deal: “First of all, I don’t think there’s any solid evidence that they were three to six months away from a balance of payments crisis. I think that were we to reject a deal that the rest of the world thought was fair, and that by, I believe any honest assessment, is a good deal for the United States and Israel, commanding adherence to our sanctions regime would become difficult if not impossible. Yes, we have the ability to punish, but can you punish everyone? If there is a concerted decision to ignore, can we be economically at war with all of Europe and all of Asia and all of Africa? There’s a limit… We insisted throughout the adjacent nuclear negotiations that we do not relieve sanctions unless Iran made the kinds of changes that we were demanding in terms of rolling back their nuclear program. Whether it was shipping out uranium, dismantling and disabling their reactors, destroying their heavy water reactor, there was a range of things they did – some of them irreversible – which met the standards that we and the world set out to accomplish. There were things that were difficult in the negotiations. I can tell you, as somebody who sat through meeting after meeting, I on many occasions would raise issues of things that would be difficult to defend, and negotiators would go back and they would do better. The snap-back provisions are the most effective snap-back provisions one could ever imagine designing. They were automatic essentially – nobody can veto if Iran violates the deal.”

“A lot of people have raised questions about what happens 15 years from now. I don’t think there’s any serious observer who doesn’t think the world is safer today because of the Iran deal, and I would argue that 15 years from now, that will be the case as well. The idea that somehow the Iran deal was not in Israel’s interest is something I disagree with. I think Israel is safer today than it was before the deal when Iran was genuinely approaching having a nuclear weapon. That’s not to say that it’s a safe world where you can take your eye off the ball. You have to stay focused.”

Lew on how he dealt with criticism over the Iran deal in the Jewish community: “I felt fine to walk into my synagogue. I live in a great community in Riverdale where I know there are people in the room who might not agree with me. I didn’t have one hostile word on Iran in that room.”

— On the heckling incident at the Jerusalem Post conference: “I knew I was going into a room where people would disagree with me. I actually had gone for the purpose of making the case to people who didn’t agree. It’s not that hard to have a good session with people who agree with me. The challenge is to try and get people who don’t agree with you to listen. What I didn’t expect was that the level of civility and openness to discourse was so low in that particular room that heckling was considered to be an appropriate way to deal with an invited guest. I don’t think that’s okay. I don’t think it’s okay on campus, I don’t think it’s okay at a Jerusalem Post event. Interestingly, the program that day was one where many of the speakers knew me well, and one after another, whether it was a conservative member of the Prime Minister’s cabinet, or Natan Sharansky, they used the first five or ten minutes of their time to chastise the audience, saying, ‘That’s no way to treat anyone in terms of being respectful in the way you treat a guest, certainly not a friend of Israel who has for his whole career been there doing things to help the State of Israel.’ I got a call from the Prime Minister [Benjamin Netanyahu] to apologize for the way I was treated. I said, ‘Look, I’ve been in rooms where people have been rude before, I can take it.’”