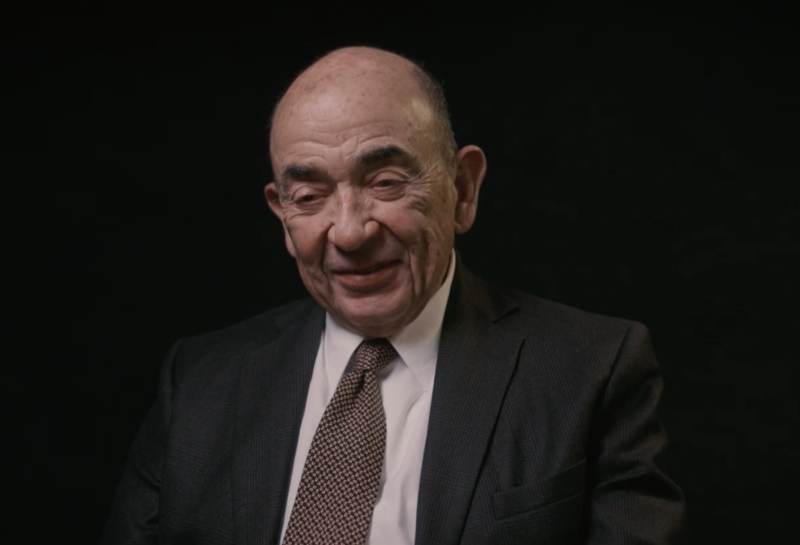

How Menachem Kaiser came to explore the secret Nazi tunnels

In his first book, 'Plunder,' Kaiser seeks to reclaim the Polish apartment building once owned by his Holocaust survivor grandfather

Courtesy

Menachem Kaiser and his new book, 'Plunder.'

In his first book, Plunder: A Memoir of Family Property and Nazi Treasure, Menachem Kaiser details his experience returning to Poland with the intention of reclaiming an apartment once owned by his grandfather, who survived the Holocaust. The process of laying claim to the property in Sosnowiec was a bureaucratic nightmare as he sought redress through the Polish court system.

But the book gains momentum when Kaiser embeds with a group of rambunctious Silesian treasure hunters who guide him through the elaborate Nazi tunnel system known as Project Riese, located in modern-day Poland. “It was as if I’d stumbled onto an alternate Poland,” Kaiser writes, “where the history was of a different mode, a different mood.”

The thread that unites these two seemingly opposing narratives is Kaiser’s previously unknown cousin, Abraham Kajzer, the author of a memoir, Za Drutami Śmierci, which describes the time he spent as a slave laborer in the tunnels during the war — a story revered by Polish treasure seekers who regard it as a kind of Rosetta Stone to locating lost valuables.

In a recent interview with Jewish Insider, Kaiser, a 35-year-old writer and journalist who grew up in Toronto and now lives in Brooklyn, discussed the process of working on the book and hinted at his next project.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jewish Insider: What’s the reaction to your book been like so far?

Menachem Kaiser: Really gratifying. The New York Times ran a review last week, so that has kind of changed the profile of the book rather dramatically. But that doesn’t really mean that many more people have read it already. A couple of my close friends have read it. My parents have read it. It is a family story, so having your family read it is always going to be interesting. But so far, they’ve been really supportive. They had some notes, some of which I was able to address, and some of which I wasn’t.

JI: Will the book be published in Polish?

Kaiser: No Polish yet. It’s a place I feel quite committed to, and it would mean a great deal for me to have the book published there. So I’m confident it will happen eventually. As of now, foreign rights have been picked up in Germany, Netherlands, the U.K. and Australia, I think.

JI: Do you think it’ll be hard to publish there given the Polish government’s role in stifling historical analysis of the Holocaust.

Kaiser: It’s hard to know how much that has an effect, but certainly there’s a pretty vibrant publishing community and industry there. So if it’s not right for one press, it could be right for a more independent press or a smaller press. But I’m pretty committed to really doing everything I can to see it be published in Poland.

JI: Can you describe the process that took you to Poland in the first place to reclaim your grandfather’s apartment?

Kaiser: Most of it happened kind of accidentally. I moved to Lithuania in 2010 for reasons that had nothing to do with family history. I did a Fulbright there, and ended up studying at the Vilna ghetto. While I was there, I had this chance encounter with this really colorful character who invited me to come with him to Krakow, which is where he spent a lot of time for Rosh Hashanah. That’s why I initially went to Poland. I had never really planned to go. I never planned to not go, but it wasn’t really on my map, even though my grandparents are from there. We didn’t grow up in my family with this idea of making that pilgrimage. Some of my siblings have gone on March of the Living and stuff like that, and some haven’t. It would be nice to go, but it wasn’t seen as anything mandatory. So I went, initially, really for nothing to do with my family, really just to go for Rosh Hashanah. But once I was there, I felt like I should at least make a visit to my grandfather’s hometown. So I went to Sosnowiec. My father gave me this address, he dug it up, and I visited the building, and then I left. For many years, I never really thought I’d ever go back. I never really felt there was any reason to go back. I thought it was a one-time thing — see the building, take pictures. I had a meaningful interaction, and that felt sort of done, like a complete journey.

JI: Then what happened?

My father kept mentioning that he had these documents in the house that belonged to my grandfather, and it never really felt that urgent, so it took me like quite a few years to sort of get around to reading them. And these documents were sort of what my grandfather, when he died, had given to my grandmother, and my grandmother had given to my father, which were all the different applications and documents and letters that had tried to reclaim the building, or at least be compensated for it from after the war for, like, 20, 30 years. I never knew my grandfather, and I never really knew that much about him, but reading those documents was quite moving, and it really inspired me to sort of enter these questions. I felt very interested, and it was like a sentimental encounter. But even at that point, I wasn’t that interested in writing a book. I didn’t really see where the book was. I saw this as, like, a personal journey. I contacted a lawyer in 2015 and that whole mishegoss started, and then about a year later, the extra mishegoss with the treasure hunters began — and at that point, I thought, here’s a book.

JI: You originally considered writing this book as a novel. Can you elaborate on your thought process there?

Kaiser: I didn’t quite set out to write it as a novel. But it was a sort of question in the back of my mind, because of all the difficulties I encountered, if it would have been better served writing it as a piece of fiction rather than as a memoir, for two main reasons. One is that I never knew my grandfather, and I don’t actually learn that all that much about him in the course of writing the book, even though it’s him that I’m trying to connect to. So in a novel, I would have been sort of granting myself the license to imagine him, to create those emotional stakes and also to project onto the character what this means — instead of me trying to. At every point, I sort of have to question the moral authority of the quest, because it’s getting mediated. I never lived there, it wasn’t my building, I didn’t grow up there. So all those questions sort of become moot if I could just imagine the protagonist. The second reason is that because it was so messy. As a court case, it was so nonlinear. In a novel, it’s whatever I wanted it to be, like I can sort of make it much neater. And I was really worried the whole time writing the book that it wouldn’t have an ending. I sold the book while the court case was still very much ongoing, and I was very nervous. As the months ticked on, and there was no resolution, it wasn’t clear to me how I could end it. If it was a novel, I could have just made it up.

JI: Dwight Garner mentions in his Times review that the tone of your memoir reminded him of Jonathan Safran Foer’s first novel, Everything Is Illuminated. Did you have that book in mind, or any other works of literature that deal with the Holocaust, when you wrote this memoir?

Kaiser: No, not really. Jonathan Safran Foer’s is a novel, and I was very explicitly not writing one of those. It’s interesting how that book has sort of now laid claim. Like, if you have high jinks in Eastern Europe, you’re now going to be compared to that. And if you’re like a Jew writing funny, weird, sort of surreal things, it’s going to be compared to that book. I was very conscious of the genre, because I think it’s a tricky one to write in, just because it’s sort of Holocaust-adjacent. It’s just something that is very charged, how to write honestly about it and about your experiences in it are never clear. It’s a thing people care a tremendous amount about, and that’s why I was so hesitant to write this book in the first place because, not that it’s really about the Holocaust, but it’s within that category, and I sort of wilted at the prospect of trying to write into that memory space. It’s such a charged space. I didn’t really feel up to it.

JI: Poland has a pretty poor track record when it comes to acknowledging the Holocaust, but it also seems like there’s, interestingly, a fair bit of philosemitism in the country. For instance, there’s a popular Jewish culture festival in Krakow. What do you make of that?

Kaiser: Let me preface by saying I’m not an expert in this stuff, and I think it’s really important to be really honest about my ignorance. I don’t speak Polish, so any sort of insight I have into Polish society writ large is going to be really limited. But my experience is I started going to Poland, and I was going pretty consistently, in 2011. So for years and years and years, it felt like it was on a really incredible trajectory. Everyone I would meet was so overwhelmingly supportive and curious, and there was just tremendous institutional support. There is a tremendous amount of curiosity and support for Jewish history. The Jewish festival you mentioned is a great example, which is completely fueled by non-Jews. That was my experience, and it did feel like a slow but steady sort of process toward a true reckoning. For example, it did feel way ahead of where Lithuania was, which had very little institutional support, and you wouldn’t meet that many locals who were invested. In Poland, people are doing their PhDs, for example, on questions of Jewish history. It just felt really deep and a real reckoning.

Then in 2015 a new government came to power. It was the Law and Justice Party, a sort of unapologetically nationalist, Euro-skeptic, far-right party. So, politically, they do what’s sort of politically expedient, and they’re not out-and-out Holocaust deniers, but their certain sort of Polish nationalism has been very evident in terms of, like, how they are operating museums. History in Poland is very political, especially World War II history, and so you’ll have government departments dedicated to preserving memory. These things end up really being very political questions that are fought in government rather than in various institutions. So that has been very dispiriting. The last few years, there’s been this slow and steady assault on historical integrity.

JI: Can you talk about the mix of emotions you felt when you went back to reclaim the apartment?

Kaiser: When I initially began this journey, I had a very sort of, let’s call it, inherited conception of my mission, which was very — myopic is too strong of a word, but it didn’t really care or consider the people who live in the building. That wasn’t really part of the equation. It was like, you know, my family owned this building, and I’m coming to take it back. That’s the narrative. And in the book, I really struggle. I get pushback, which was really surprising and upsetting to me at first, of people accusing me of appropriation. I found that very upsetting, and I have a very strong reaction to that in the sense of like, no, my legal and moral right aren’t really questionable here. Yet a message does get through, which is your actions will have effects on people. And so you have to take that into account without sort of compromising your moral slash legal right.

That becomes really a question of narratives. So I ended up going into the building and meeting some of the people and developing relationships with them, which was sort of expanding the frame, if you will, if you sort of take into account the story of a building, and that story doesn’t start when the Jews moved out. You start framing the question as more than just ownership. And it’s very tricky, it’s very complicated, and people are going to be upset. And even if I don’t really have any compunctions about the moral right, I’ll be the first to say that it is very complicated. It didn’t seem complicated when I started, and that’s because my vision was pretty narrow, but as I continued on, that kind of expanded. I would like to think my sort of moral range got wider in taking into account the people who actually lived there.

JI: What was it like hanging out with these tunnel people?

Kaiser: I spent a ton of time with them, especially after they realized I was related to Abraham. They sort of regarded me as a celebrity. They’re interesting. They’re a little hard to describe within an American context, because there isn’t really an analog here. The way I ended up describing them is, like, somewhere between war reenactors and extremely amateur archeologists. There’s a range of them in terms of how professional they are, and so you have like some guys who are just real hobbyists who just go out on the weekend with metal detectors, and then you have guys who have really sophisticated, expensive equipment, and sometimes they’re even sponsored by larger companies. So a real range, hanging out with them. Definitely the more serious ones, or at least that I met, were more rural, though that’s not always true. They tend to be male, but not all of them. Kind of macho, sort of, a little bit of bravado. They definitely drink.

They’re having fun. They form these exploration groups, and some of them have been together for 20 years. They’re friends. But it is a subculture, and it’s a very active subculture. And so they have their own weird politicking, and their weird fights, and their disputes and alliances. But everything sort of changed in 2015, when two of these guys claimed to have found the golden train. And when that happened, the world took it very seriously, and they got international media attention for a few months. I wasn’t there; I came in the aftermath of that. But there was a lot of attention, and so all of a sudden, the pie got bigger, and to the extent there’s competition, it got a lot fiercer. So that was in recent memory, what they call the golden train fever.

JI: Do you still talk to them?

Kaiser: They’re very active on Facebook, so when it’s my birthday, I’ll get tons and tons of messages from them. They’re really excited about the book. A lot of them don’t speak English, so I would need a translator, but I’m definitely in touch with a few of them.

JI: What do you think books about the Holocaust will look like after all of the survivors have died and there is no one left who can bear witness?

Kaiser: Ultimately, I don’t know. I guess it sort of fades into background history in 10 generations or something. But for the time being, I think we’re transitioning into a literature that reckons not just with the event, but with the memory of the event. And so for many of us who don’t have first-hand experience, we have very intense second-hand experience. I think we’re moving into that space. I think the first-person testimony is the most important and the most powerful mode, and I think, in a lot of ways, for a while, people tried to replicate that, even though they didn’t have that, like people sort of writing with that distance, but not necessarily being super honest about that distance. But within my little circle of friends, many writers and artists who are Jewish and who have grandparents or great grandparents from that region and who are affected by the trauma, I think that becomes the more compelling artistic question of, like, we’re not going to really reckon with the event. We don’t have anything to say about the Holocaust itself. But in a personal way, we sort of reckon with our experience of the memory of it, whether we see that as a burden, a responsibility, a trauma, or sort of the binds in our family. I just think that’s a very pressing question, in my limited view, that seems to be becoming more and more prominent.

JI: Do you ever intend to go back to Sosnowiec or to the tunnels?

Kaiser: Those are a little bit different questions. The court case is still ongoing, and so now this stuff is going to be done via Zoom for at least the foreseeable future, but I would be very interested if and when all the court stuff comes to a close. It would be meaningful for me to sort of be there for whatever the final event is. I’d like to be there. I would go back. The tunnels are spectacular. They’re very strange and very disturbing, but pretty wild in person. So I’m hoping when COVID becomes less of an impediment to go back and maybe throw a really big book launch party in Poland. That would be fun.

JI: You get into conspiracy theories in your book. What do you make of the rise of antisemitic conspiracy theories in the U.S.?

Kaiser: One of the lessons I took from my book and studying these conspiracy theories is that stuff that seems really benign because it’s so preposterous has a really dark underbelly. We’ve gotten really used to laughing at really silly things. Like QAnon, for example, stuff that seems laughable, it could still very quickly sort of coalesce into something very dangerous. And that’s something I saw with these sort of really ridiculous Nazi conspiracy theories, and that people believe them or say they believe them, and you’re like, it doesn’t seem harmful. When someone’s like, yeah, the Nazis had flying saucers, you’re like, that seems silly. But when you start really bearing down on what that means, and what that sort of system of beliefs imply, it becomes a really noxious kind of revisionism, and whether the adherents of these conspiracy theories know that or not, it ends up encouraging and attracting some really noxious beliefs. A recent example of that is the Jewish space lasers from Marjorie Taylor Greene. She said it, and we all had a good laugh at it. It’s so silly, and it seems harmless. But these things sometimes work in ways that are not visible, how belief structures work and the communities that form around them quickly become very dangerous.

JI: You were raised Orthodox. Are you still?

Kaiser: Let’s pass on that question.

JI: Are you working on anything new?

Kaiser: I have a basically finished novel that I wrote in grad school about radical, somewhat terrorist Yiddish poets in interwar New York City. I haven’t had the chance to go back into that for a few years, but I’m looking forward to dipping back in.