Screenshot

Ehud Bleiberg on the true story behind Netflix’s ‘Image of Victory’

The film, released to American audiences on Friday, tells the story of the Battle of Nitzanim during Israel’s War of Independence, in which kibbutz residents were taken captive by Egypt

As Arab forces waged war on the fledgling State of Israel in May 1948, mere days after David Ben-Gurion mounted a Tel Aviv platform to proclaim the establishment of the Jewish state, a mother kissed her 3-year-old son goodbye, handing him a note explaining, “I am giving up my child so that he will grow up in a safe place, to become a free person in his new country,” as she abandoned her only child with fleeing kibbutzniks to defend her kibbutz — one of many fronts in the war that would shape Israel’s future.

That woman — Mira Ben Ari — is the protagonist of Ehud Bleiberg’s new feature film, “Image of Victory,” released to American audiences on Netflix today, after enjoying success in Israel since its release in December. A feisty feminist who refused to evacuate the kibbutz along with other women and children, Ben Ari fought until the bitter end of the battle for Kibbutz Nitzanim in southern Israel, until being shot and killed by Egyptian forces.

Bleiberg, the CEO of Bleiberg Entertainment whose notable titles include “The Iceman” (2012) and “The Band’s Visit” (2007), has long planned a film about the Battle of Nitzanim owing to a very personal link — his father fought in the campaign and was taken captive by the Egyptians.

“This film just came to show what really happened — what you see in the film is what happened more or less,” Bleiberg told Jewish Insider in an interview. “A group of great people — innocent, very naive people, happy people, 21, 23, 18, 19 [year-olds] — the sky became gray and everything [came] against them.”

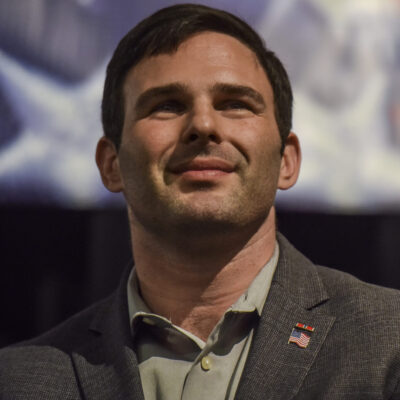

Producer Ehud Bleiberg speaks during the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival at TIFF Bell Lightbox on September 10, 2012 in Toronto, Canada. (Photo by George Pimentel/WireImage)

One of those people was Bleiberg’s father, Yerah Bleiberg, who moved to Mandatory Palestine at the age of 14 in 1938, studying agriculture in the Ben Shemen youth village, where he roomed with future statesman Shimon Peres.

The elder Bleiberg moved to Nitzanim, which was founded along the Mediterranean coast in southern Israel in 1937 by a group of young pioneers of the Noar Hazioni youth movement, and worked as a dairy farmer on the kibbutz.

The movie’s plot closely mirrors actual events during the 1948 battle. The Haganah paramilitary organization sent a platoon from its Givati brigade to shore up Nitzanim’s defenses, and helped the kibbutz wage a relentless defense against Egypt’s unexpected attack, despite being undersupplied and outgunned. Ultimately, the kibbutz members and Givati forces surrendered the settlement and were taken captive by Egypt. A separate 33 Jews — 17 soldiers and 16 kibbutz members — were killed during the fighting.

After the defeat, Givati official Abba Kovner insinuated that the surrender of Nitzanim was not justified and castigated Nitzanim’s residents for cowardice.

“Surrender, as long as there is breath in our body and a bullet in our gun, is a disgrace,” he wrote in a memo. “To surrender is disgrace and death.”

Eventually, the kibbutzniks were cleared of wrongdoing in a commission led by IDF Chief of Staff Yaakov Dori; Kovner, however, never apologized for his initial accusation.

For years, Yerah Bleiberg did not breathe a word of the harrowing humiliation he suffered at the hands of his fellow Israelis, and his son Ehud only learned about Kovner’s letter when reading the newspaper as an 18-year-old.

“I was furious,” he recalled, explaining that he views his father’s efforts as a heroic attempt at a doomed effort to save the kibbutz, which the Haganah did not adequately equip with defense materials.

Bleiberg explained the Haganah’s decision not to heavily arm Nitzanim was rooted in a “stupidity of the strategic view of where the Egyptians will go when they invaded Israel,” which assumed Egypt would not move along the coast, and also “because they care[d] less about the kibbutz, they took care of more of their own people first.”

“They deserted them, from my point of view,” Bleiberg said.

Eight years ago, when sitting shiva for his brother, Bleiberg turned to his sister and said, “If I’m not going to make this film right now, I’m not going to make it,” echoing the rabbinic sage Hillel, who asked, “If not now, when?”

Bleiberg then embarked on what turned out to be a large-scale project, tapping Israeli director Avi Nesher for the production that was esteemed to be the most expensive film shot in Israel, costing about $5 million.

The crew built a full-scale replica of the original kibbutz, and then blew up the set for the scene depicting Egypt’s air strikes on the settlement.

Bleiberg called Ben Ari, whom he chose to spotlight in the film, an “amazing character. Before feminism was discussed, she was a feminist.”

Ben Ari, an unconventional figure for her time, helped operate the radio system on the kibbutz, and insisted on fighting alongside her male peers. The film hints at a romantic involvement between Ben Ari, who was married, and Avraham Schwarzstein, the Givati commander tasked with defending Nitzanim.

Bleiberg and Nesher relied on Ben Ari’s diary to tell her story, and obtained permission from her family to cast her as the story’s main character.

At the climax of the battle, Egyptian fire hit Schwarzstein, and Ben Ari avenged his death, firing with her revolver at the Egyptian officer who killed Schwarzstein.

Nesher put his own stamp on the production, suggesting that the story follow an Egyptian wartime documentarian named Hassanin, who was recording the Egyptian assault.

A still from “Image of Victory”

The film opens with Hassanin enthralled with the look in Ben Ari’s eyes as she shoots at the Egyptians, with him narrating, “It’s crazy. Of all the men and women I met in my life, it’s her I cannot forget.”

The Egyptian filmmaker is another detail based on the actual events, and Egyptian footage depicts kibbutz members being marched by Egyptians with their arms held up in surrender.

The framing device of the Egyptian documentarian necessitated telling the Egyptian version of the attack, a twist that adds to the film’s complexity and upped the production costs.

“The Egyptians are human beings too and we’re human beings, but we never know who they are,” Bleiberg explained, hoping that “Image of Victory” can tell a rich historical story with multiple perspectives.

Arab Israelis portray the film’s Egyptian characters, and the Arab and non-Arab actors befriended each other during the shooting.

“The way that Avi [Nesher] portrayed [the Egyptians] and the way that Avi behaves with [the Arab Israeli actors] and the way the production behaves with them gave them the feeling that we are not trying to be superior to them,” Bleiberg said. “On the other hand, we don’t have to agree with their political view, but we are friends.”

During the shooting, one of the Israeli actors who had served in the IDF’s elite Sayeret Matkal unit showed the Arab Israeli actors how to use weapons.

The resulting film humanizes the enemy and underscores how both sides in the battle were comprised of regular people.

“The Egyptians are human beings too and we’re human beings, but we never know who they are,” Bleiberg explained, hoping that “Image of Victory” can tell a rich historical story with multiple perspectives.

Several messages shine through in the film, including Bleiberg’s frustration with the accusations leveled against the Nitzanim residents and the cruel nature of war.

In the movie, an older Hassanin rails against the 1979 Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty, wondering about the futility of the fighting between countries that would ultimately sign a peace agreement three decades later.

Hassanin’s fictional reaction differs from Bleiberg’s father’s response to the peace.

“When there was a peace treaty in Egypt, it was one of the most happy days of my father, and mine as well,” said Bleiberg. “He never hated them.”

While the film does not cast judgment on the Egyptians, it criticizes the accusations leveled at the kibbutzniks over their surrender. An infuriated Hassanin narrates that both Israeli and Egyptian captives during the war were treated poorly and ridiculed for their captivity.

“He who was not in that terrible war, shouldn’t judge those young people,” Hassanin says, sounding like the 18-year-old Bleiberg upon discovering Kovner’s letter.

At the end of the film, Hassanin describes his footage as the “image of victory” that was sought by his patron, King Farouk of Egypt. But it is also Bleiberg’s image of a brave group of valiant fighters who ferociously defended their kibbutz until surrendering — before more lives were lost.