Can Glenn Youngkin stem the blue tide in the Old Dominion?

The former Carlyle CEO running for governor in Virginia hopes he can win over Republicans and moderates by avoiding Trump, but is going all-in on conservative culture war

For most of the last 12 years, Republicans in Virginia have been wandering in a political wilderness.

They watched in despair as Democrats swept statewide elections in 2013, then nearly won control of the General Assembly in 2017 — the final seat resulted in a tie that was broken when the Republican’s name was pulled out of a bowl — before going on to wrest control of the House of Delegates and State Senate in 2019. Republicans’ poor electoral fortunes were not limited to Richmond; former President Donald Trump lost the state by five points in 2016, but lost it by 10 points four years later.

As the Virginia gubernatorial race begins in earnest, Democrats in the Old Dominion seem to think the status quo is working. In a landslide primary election earlier this month, Virginia Democrats nominated Terry McAuliffe, the prolific national fundraiser who already served as governor from 2014 to 2018. (The state bars governors from serving two consecutive terms.)

But the GOP hasn’t given up on Virginia yet. From a primary field of well-known Republican politicians ranging from business-friendly state lawmakers to a self-described “Trump in heels,” Republican voters chose Glenn Youngkin, a political newcomer who most recently served as chief executive of investing giant The Carlyle Group. Youngkin has touted his business bona fides while running a campaign that’s scant on policy details, in the hopes of appealing to both the Trump-supporting base of his party and the suburban swing voters who overwhelmingly shifted to Democrats during the past administration. His clearest argument seems to be that he is a new face on the scene — and he thinks Virginia needs change.

“I think common sense has been checked at the door,” Youngkin told Jewish Insider in a recent interview at his campaign headquarters in Falls Church, Va., just inside the Beltway. He was wearing a white Oxford shirt with his campaign logo — the words YOUNGKIN GOVERNOR above the shape of Virginia — embroidered in red. “Being an outsider who brings a fresh perspective, I can say things like, ‘Well, why in the world do we do it like that?’”

Despite Democrats’ good fortunes in Virginia in recent years, a win is not a guaranteed outcome for McAuliffe. A recent poll showed the former governor beating Youngkin by only four points, a surprisingly close margin. Yet unlike 2017, when national money poured into the state’s down-ballot races, Virginia Democrats worry those donors might feel they no longer need to invest in Virginia. “We’ll have a challenging time convincing national donors that Virginia is at risk,” a former Democratic state official told JI.

ANNANDALE, VA – MAY 8: Gubernatorial candidate Glenn Youngkin works the line of cars as the Virginia GOP holds a drive through primary to select candidates for the 2021 general election, in Annandale, VA. (Photo by Bill O’Leary/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

“A Republican can win in Virginia,” said Mark Rozell, dean of the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University. “There are many analyses that I think are overstated, that claim that Virginia is a solid blue state now strongly in Democratic hands, and nearly impossible for Republicans to win statewide. We’ve been here before.”

In an interview with JI, Youngkin provided insight into how he plans to address two of his major priorities — education and the economy — and expressed concern over rising antisemitism in Virginia and around the country. Unlike many Republican Senate and House candidates who are clamoring for Trump’s endorsement, Youngkin did not mention the former president over the course of the interview.

“He’s making, I think, the right choice in presenting himself now as a mainstream, conservative Republican, and trying to move away from the taint of the Trump era,” said Rozell. “All of that is complicated by the fact that Trump gave a full-throated endorsement of Youngkin, and Youngkin responded by saying he was honored to have that endorsement.”

Since winning the Republican nomination at a statewide nominating convention last month, Youngkin has shied away from mentioning Trump on the campaign trail. This marks a change for Youngkin, who ran a markedly more conservative campaign in the primary, when he touted his Election Integrity Task Force, and refused to say whether President Joe Biden was legitimately elected. Just days after clinching the nomination, he began to acknowledge Biden’s election as legitimate.

He has also avoided taking concrete positions on culturally conservative issues like abortion and gun rights. His campaign website does not have an issues page, and a Washington Post editorial criticized Youngkin for “mastering the duck and the dodge.”

Democrats’ strategy involves taking Youngkin’s lack of concrete policy proposals and tying him to Trump, but Youngkin is attempting to pre-empt that by running TV ads across the state, part of his decision to invest millions of his own dollars into his campaign. “It’s giving Youngkin the opportunity to define himself prior to the time that the Democrats define him,” said Bob Holsworth, managing director at DecideSmart, a Virginia-based political consulting firm.

While Youngkin is tiptoeing around Trump’s legacy, he is offering a full-throated endorsement of the latest front in national Republicans’ culture war: the battle in school boards across the country, including in Virginia, over critical race theory.

“He’s making, I think, the right choice in presenting himself now as a mainstream, conservative Republican, and trying to move away from the taint of the Trump era,”

Mark Rozell, dean of the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University

“What critical race theory is clearly about is, first, identifying people by the color of their skin and dividing people into groups, and then providing judgments on those groups,” Youngkin explained. The term refers to a legal theory, which has historically been reserved for college courses, that asserts that racism is systemic in the U.S. Over the past few months, as many school boards around the country have mandated instruction about racism following widespread racial justice protests, the term has come into popular parlance.

Critics of critical race theory argue that teaching children that white Americans have “white privilege” due to their race, while Black people and other people of color are at a disadvantage, encourages strife between racial groups. “It doesn’t mean we shouldn’t talk about the challenges that so many folks and particularly black Americans have faced,” Youngkin noted. “In fact, it kind of pits kids against one another. And this just isn’t right.”

Republicans like Youngkin seek to limit recent school board curriculum changes that now mandate the teaching of topics like white supremacy and racism in greater detail.

“It was, in fact, mandated through the Board of Education, that we were going to teach this in the schools. We will de-mandate that,” said Youngkin. He did not provide further details on how he will attempt to fight critical race theory. “The goal is for us to actually not judge people by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character and by opening up opportunity for everyone,” he explained, quoting Martin Luther King, Jr.

The Board of Education is a commission whose members are appointed by the governor, and Youngkin would not have sway over the board until its current members’ terms expire, beginning next year.

In response to the racial reckoning that occurred last summer after George Floyd’s murder, the state Board of Education adopted some changes to Virginia’s state history and social science standards last fall. But the new standards do not refer to “critical race theory,” and ultimately most decisions about how to adapt those standards into concrete curriculums occur at local school board levels, which would be out of Youngkin’s direct control as governor.

WASHINGTON, DC – APRIL 29: (L to R) Suzanne Youngkin, Glenn Youngkin and former U.S. Secretary of Labor Elaine Chao attend Capitol File’s book release party for Kelley Paul’s “True and Constant Friends” on April 29, 2015 at ENO Wine Bar in Washington, DC. (Photo by Paul Morigi/Getty Images for Capitol File Magazine)

Still, Youngkin and Republicans think the message sells. Critical race theory “clearly has some political appeal” as a campaign talking point, said Rozell. “If the Republicans can actually pivot away from the Trump era, and turn the tables, and try to characterize the Democratic left as having gone way too far, there may be a strategy there to win over some swing voters in the critical suburbs and exurban communities.”

Jewish Republicans think the message is resonating in their communities, too. “I think it’s an issue that has really taken hold,” said William Kilberg, a former partner at Gibson, Dunn and Crutcher who served as solicitor for the U.S. Department of Labor in the Nixon administration and who lives in McLean. “I think people are very concerned. They’re seeing a lot of it in the schools, both public and private.”

Rabbi Dovid Asher of Keneseth Beth Israel, an Orthodox synagogue in Richmond, expressed concern that curriculum changes could target Jewish students, or unfairly leave out Jewish history. (The edited standards adopted by the state last year include the Holocaust, which has long been part of the state standards.) “I think a lot of us are concerned about efforts in other states, like California, in terms of what is going to be adopted or ratified for the curriculum, and whether Jews are going to be left out, or even worse, kind of attacked for a misunderstanding of our history,” Asher said, referring to the California state ethnic studies curriculum whose early iterations were widely criticized by the Jewish community for leaving out Jews and targeting Israel. “We certainly would like allies on the inside that have power with regards to these issues, to be more inclusive of the American Jewish narrative.”

In contrast to other Virginia Republicans who have run far-right campaigns in recent years, Youngkin has tried to present his campaign as a big tent; he put out a statement recognizing Juneteenth and last week announced a Latinos for Youngkin coalition.

“What’s been interesting is the enthusiasm for this campaign. What we’re doing is not just Republicans, it’s actually Republicans and independents and a lot of Democrats,” Youngkin told JI.

Still, Youngkin is new to electoral politics, and building a coalition is difficult if voters don’t know who he is. A graduate of Rice University and Harvard Business School, Youngkin worked at Carlyle for 25 years. He has donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to Republican politicians, but was not widely known as a major donor.

Youngkin’s relative novelty also extends to the state’s Jewish community. “Most of my Jewish friends, candidly, are either in New York or Texas,” Youngkin said when asked who he is close to in Virginia’s Jewish community. Youngkin’s former colleague David Rubenstein, the Carlyle founder and a prominent Jewish philanthropist, declined to comment, noting through a spokesperson that he does not weigh in on political topics.

Youngkin is active in faith circles; he served as church warden at Holy Trinity Church in McLean, and until he ran for office, he was on the board of trustees at the Museum of the Bible in Washington. Funded by the Green family, the evangelical Christian family that owns Hobby Lobby, the museum aims “to invite all people to engage with the transformative power of the Bible.”

“What I loved about the museum — when I was in an exhibit, and I looked around, there were folks from every possible faith persuasion, and none,” Youngkin said. “There were folks from all ages and ethnicities learning about the Bible, and for all kinds of reasons: curiosity, to deepen a religious understanding, it was really neat.”

Last week, Youngkin unveiled a plan to combat antisemitism — his most specific policy proposal to date, on any topic. He pledged to create a “Virginia Holocaust, Genocide and Anti-Semitism Advisory Commission” and work with the General Assembly to adopt the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s (IHRA) working definition of antisemitism. The plan appears to be modeled off a bill that passed in Texas last week, which will adopt the IHRA working definition of antisemitism and create a state commission of the same name as the one in Youngkin’s proposal.

“Antisemitism is on the rise, and actually violence is as a result of, I think, a lessening of understanding of, one, we have to treat each other with deep respect, but also, why do we teach about the Holocaust in Virginia? It’s to make sure that Virginians understand and can remember,” Youngkin explained.

McAuliffe has not released a concrete plan on confronting antisemitism, but his website notes that he intends to “improve identification and enforcement of hate crimes.” Reached for comment this week following Youngkin’s proposal, McAuliffe mentioned the deadly 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, which he called “a grim reminder that antisemitism and white supremacy are alive and well in our Commonwealth and in our nation” and noted that Youngkin’s “top endorser Donald Trump…called these domestic terrorists ‘very fine people.’” (In response, a Youngkin spokesperson noted that “the anti-Semitic march in Charlottesville was an abhorrent demonstration of hate that has no place in America.”)

Youngkin’s spokesperson told JI that when crafting the proposal, the campaign had consulted with Rabbi Yaakov Menken, managing director of the Coalition for Jewish Values, a conservative advocacy organization, and Rabbi Gershon Litt, the Hillel director at the College of William and Mary. When contacted by JI, both rabbis said they were approached by the campaign after the fact and asked to give a quote praising the proposal.

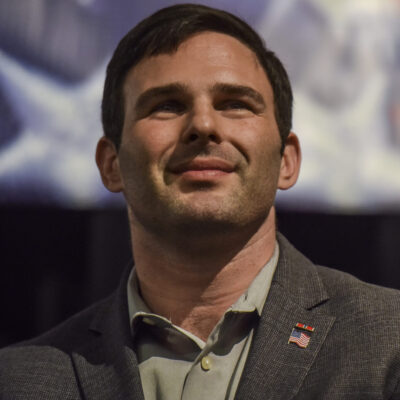

Glenn Youngkin

“I just gave a quote about the legislation but I have never spoken with the campaign,” Litt said. Menken said a campaign official called and gave him an overview: “I didn’t even look it over. She kind of ran it by me,” he noted. “I said, ‘That sounds like a great idea.’”

Other politically conservative Jewish community leaders agree that they are just now beginning to learn about Youngkin, but some like what they have seen so far. Kilberg believes the Youngkin campaign is trying to reach Jewish voters. “I have no doubt [he] will,” Kilberg, a longtime Republican activist, knows Youngkin from the business world, said. “He shows sensitivity out of the box. I know him better, I suspect, than most of our co-religionists because we’re more active and we’re Republicans and most Jews are not.”

Asher, the Richmond rabbi, said that Youngkin “has a little bit of a reputation, especially within the business community and with regards to his political interests and political connections, to be someone who is supportive of tradition, of religious observance, and somebody who is going to protect religious liberties.”

Several Jewish Republicans remarked to JI that Youngkin had supported the Jewish community earlier this year when the Republican Party of Virginia announced that voting in the statewide nominating convention would take place only on a Saturday, with no exception for Shabbat-observant Jews. The party eventually added a Friday afternoon voting period. “He was very supportive of that initiative and in that kind of outreach, so for Republicans in my congregation, that’s a good sign — to have somebody who could be the leader of the Virginia Republican Party be on their side for those issues,” said Asher.

Ultimately, Youngkin’s pitch comes back to his experience as an executive, which he says can help him run the state more efficiently — a classic argument for business leaders-turned-politicians, and one that McAuliffe himself has used.

On the economy, he sounds like an old-school conservative, with the goal of cutting red tape and bureaucracy. His first step will be to “make sure that any residual executive order that the governor has put in place is removed immediately,” Youngkin said. He pointed to an executive order that current Governor Ralph Northam signed in January making some COVID-19 workplace standards permanent, though a more recent order in May ended the mask mandate and eased restrictions.

He proposed offering a tax holiday to new small businesses “in order to give them a chance to get back on their feet because we need that job engine cranked back up,” Youngkin said. More broadly, he criticized bureaucratic regulations in the state. “Our job creation engine has had a blanket on it, which has really been a stack of challenging regulatory impositions,” argued Youngkin. “As a business leader, there’s just no excuse for it.”

“The comprehensive nature of the Virginia government doesn’t really intimidate me, because I’ve run something very big,” said Youngkin. “But I also recognize that I’m going to need a lot of people around me who understand how to get things done in order to accomplish many of our goals.”