Courtesy

‘Un heroe’: How a U.S. Marine saved lives after Buenos Aires Israeli embassy bombing in 1992

By pure coincidence, B.G. Willison Jr. happened to be blocks away from the attack. His response earned him accolades and lifelong friends

B.G. Willison Jr. was just passing through Buenos Aires on the day that changed his life and ended the lives of dozens of others.

It was March of 1992, and Willison — a 23-year-old junior officer in the U.S. Marine Corps — was living in South America on a government scholarship studying Spanish. He had barely any money, so he hitched a ride into the city from some Air Force pilots, who dropped him off at a café near their hotel. He didn’t know it at the time, but the coffee shop was just blocks away from the Israeli Embassy.

“I was seated right next to a big pane of glass, and I’ve never seen glass bend before. I heard the explosion, and I knew that there was something wrong,” Willison, 53, told Jewish Insider in a phone interview from his home in Dallas.

The explosion he heard was a suicide car bomb that leveled the nearby Israeli Embassy, killing 29 people and wounding nearly 250. Most of the victims were Argentinians, including a Catholic priest at a nearby church. Willison remembers the children at the Catholic school next door who “wore these beautiful cornflower blue uniforms, and I remember the images of the bloodstains on their uniforms as they tried to escort them out from the school.”

Argentina has accused Iran of orchestrating the attack, although no one has been arrested for their role in the deadly bombing.

“The thought that it was a terrorist attack never crossed my mind. I thought it was maybe a gas leak. I didn’t know that it was the Israeli embassy,” said Willison, who jumped up from his table at the café and followed the noise to the chaotic scene of the attack. “I just started pulling people out.”

All Willison knew when he saw the attack was that he had to help. After he left the café, he saw 15 feet of rubble where a building had been. Ambulances had not yet arrived; streets were blocked. “We put bodies in dump trucks and taxis. Anybody who would take people to the hospital,” he recalled. “I kept pulling bodies out until the police wouldn’t let me get in the building anymore.”

Firemen and rescue workers continue to dig through the ruins of the Israeli Embassy early on March 18, 1992, in Buenos Aires following the March 17 explosion of a powerful car bomb, which virtually destroyed the diplomatic building. (Credit: DANIEL LUNA/AFP via Getty Images)

Willison also didn’t know that, as he pulled survivors and victims from the rubble, fashioning tourniquets out of tablecloths from a nearby restaurant, a photographer from a major magazine was documenting the scene. Days later, a photo of Willison holding a bloodied and horrified-looking woman, who held onto him while he appeared to be comforting her, was published on the cover of Gente magazine, a major Argentine weekly.

Willison was unfamiliar with Buenos Aires. He didn’t know the name of the café where he had been sitting, but he left his wallet there. He flagged down a taxi to take him to the American Embassy. When he arrived and told embassy staffers what happened, he was given the surprising task of sending a report to then-U.S. Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney. “I was a second lieutenant, which is the lowest officer rank in the Marine Corps. But I was the senior person on the scene,” said Willison.

“We had a survivor’s dinner on the 25th anniversary, and we took a group photo. I was hugging everybody goodbye, and they started chanting ‘gabor,’ and I didn’t know what it meant,” he recalled.

He spent the night at the home of the embassy’s assistant naval attaché, a marked change from where he’d been sleeping during his budget tour of South America. “I’d been staying in a really nasty hotel where the night before I was killing cockroaches with the bellhop until, like, 1 a.m.,” Willison said. He’d been in South America for three weeks when the attack happened, first in Asunción, Paraguay, and then Montevideo, Uruguay.

After his brief — but eventful — stay in Buenos Aires, Willison hopped on a bus to Chile. While waiting for the bus, he stopped at a small newsstand and saw himself: the image of him holding the injured woman was on the cover of a magazine. He bought several copies.

“By the time I arrived at the U.S. Embassy in Chile, the Argentine media were in the lobby of the embassy,” said Willison. He posed for more photos and did an interview in Spanish, the first of many he would conduct with Spanish-language media over the years. But his story has rarely received any coverage in the English-language press.

A glossy spread about Willison, under the headline “Un Heroe,” told his story. It ran with an image of him in his khaki uniform, reading the previous week’s magazine that showed the photo of him rescuing Lea Kovensky. At the time, Kovensky was a 36-year-old secretary at the embassy; she went back to work after the attack, where she remained until her recent retirement. She was a native Argentinian, but she assumed Willison was Israeli and tried to speak to him in Hebrew when he picked her up.

He didn’t know any Hebrew at the time, and even now, he only knows “Shabbat shalom” and “gabor,” which means strong. “We had a survivor’s dinner on the 25th anniversary, and we took a group photo. I was hugging everybody goodbye, and they started chanting ‘gabor,’ and I didn’t know what it meant,” he recalled.

Willison is quick to acknowledge how that March day changed his life. He gained “a sense that you could get hit by the pickle truck any day, so live life to the fullest,” Willison explained. Part of what’s stayed with him is “a sense of responsibility, that, hey, I know what happened. And I’m frustrated by the fact that there hasn’t been justice.”

Willison recently went back to Buenos Aires to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the attack, where he reunited with friends he sees every five years at each memorial event.

“Even 30 years later, the Israelis celebrate him and invite him to participate in the commemoration,” U.S. Ambassador to Argentina Marc Stanley told JI. Stanley, a longtime Dallas resident, met Willison at last month’s event. “I’m sure most Americans don’t know about his heroism, and I wanted to let folks know that there are brave folk among us who engage in heroic acts and make us proud.”

No one has been charged for any role in the attack. Iran is widely understood to have plotted the attack, and some of the suspects believed to be involved in the embassy bombing are also wanted for their role in the bombing of the AMIA Jewish center that occurred two years later, also in Buenos Aires; the 1994 attack killed 85.

“It has been a sad tale of impunity and disrespect for the victims that lasts three decades,” said Fernando Lottenberg, a Brazilian attorney who serves as the Organization of American States’ commissioner to monitor and combat antisemitism.

“Iran denies it engages in terrorism but we ignore its vast record of extortion, intimidation, bombings and all means of violence, including in our own backyard, at our peril,” said Toby Dershowitz, senior vice president for government relations and strategy at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, who has tracked the many Iranian figures connected to the two attacks in Argentina.

In March, a bipartisan group of more than 100 members of Congress authored a resolution commemorating the embassy attack on its 30th anniversary and calling for “justice for the victims [and] accountability for the perpetrators.”

Every five years since the attack, the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs sends a delegation of Israelis who were wounded in the attack, or who lost family members, back to Buenos Aires. Daniel Carmon attends all of these reunions. A career foreign service officer, he oversaw operations at Israel’s embassy in Buenos Aires at the time of the attack. His wife, who worked on the embassy’s communications team, was killed, and Carmon was hospitalized for several days as a result of his injuries. After the attack, he went back to Buenos Aires with his five children — at the time, they ranged in age from 2 to 12 years old — to help them regain some sense of normalcy.

At this year’s memorial, “we had less people coming, maybe it has to do with the time that has passed, but [we] still have about 15 to 18 people go on this delegation,” said Carmon, who retired from the MFA in 2018 after 45 years, culminating in his posting as Israeli ambassador to India and Sri Lanka. “It’s a very, for me, emotional and pressing and important thing that our ministry is doing.”

Willison does not often speak publicly about what happened; the reunions are really the only time he discusses the attack. Mostly, he has kept his experience to himself. After his travels in South America in 1992, he went back to Quantico, the Marine Corps base in Virginia, and then transferred to Camp Lejeune in North Carolina. He served for four more years after the attack but never sought attention for his role in the rescue effort. While at Camp Lejeune he received a Navy Commendation Medal for “heroic achievement while in the vicinity of a terrorist car bomb explosion,” which shocked his friends.

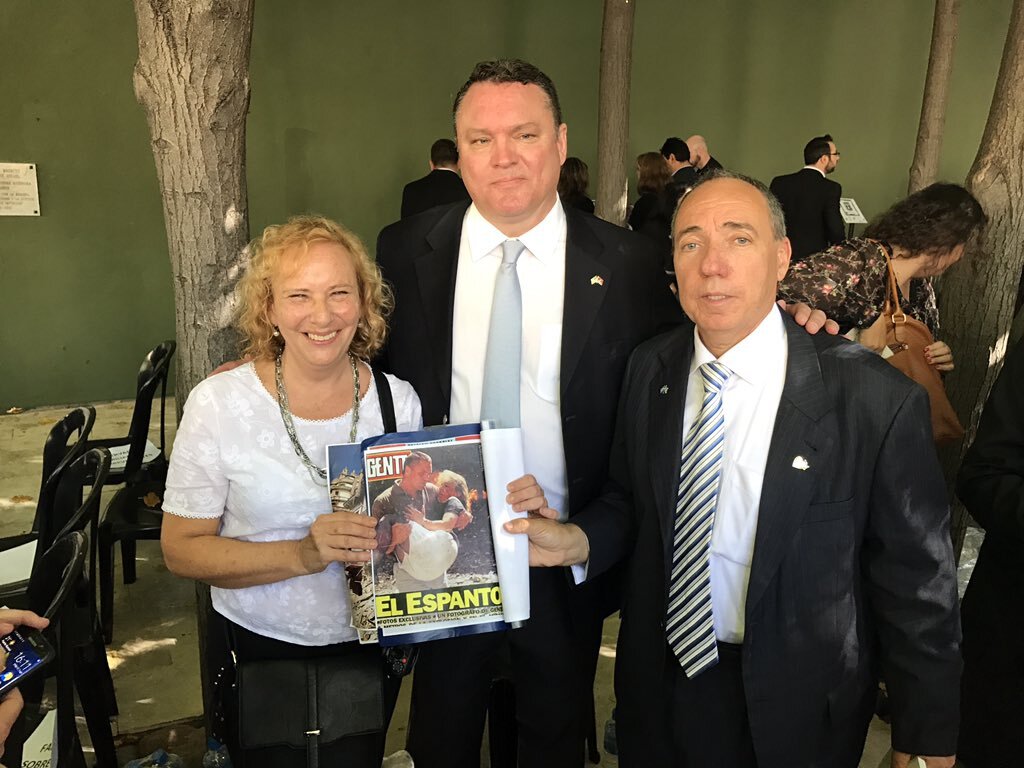

Lea Kovensky, B.G. Willison Jr. and Yuval Rotem, Israel’s deputy minister for foreign affairs

“It’s not often that a second lieutenant gets a Navy Commendation Medal,” Willison noted. The citation that accompanied the honor said Willison “personally carried ten seriously injured personnel from the area and administered life-saving first aid to five others,” and praised his “courageous and prompt actions in the face of great personal risk.”

Carmon met Willison at one of the Buenos Aires commemorations, either five or 10 years ago, but by then he was already familiar with the famous image of Willison and Kovensky. “I was very impressed when I saw him — a translation of something that you saw in a paper, in a photo, to a real person, it was very touching,” Carmon told JI.

At this year’s event, Willison brought his wife and their two teenage children. “I saw how touched and how proud they were of their father. I think it was a very, very, very important decision from their side to come as a family to the ceremony this time,” said Carmon.

Willison now works for a cloud computing startup, and he has kept a photo of Kovensky in his office for years. His children know about the role he played in the aftermath of the attack but had never been to Buenos Aires until last month. “They really felt like they too had an extended family, because everybody embraces them so warmly,” he said of his kids.

The 25th anniversary commemoration, in 2017, is when Willison and Kovensky developed a strong bond. They saw each other again a few months later in Washington, D.C., when they both spoke at the American Jewish Committee’s Global Forum. Willison received AJC’s Moral Courage Award. “We became one 25 years ago,” Kovensky said in Spanish at the AJC event. Willison and his wife later went to Buenos Aires to spend New Year’s Eve with Kovensky and her family.

“I was so fortunate that I gained so much out of a tragic event,” Willison said, “whereas so many of them lost so much out of it.”