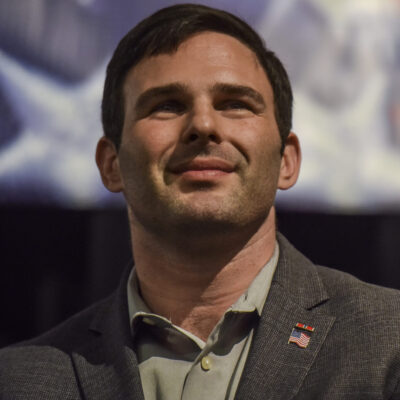

Jason Nuttle for Jewish Insider

The general who coined the Abraham Accords

How a two-star U.S. general from Puerto Rico earned the trust of the Emiratis to later help broker the Abraham Accords — and name it too

Below the holiest place in Judaism, a group of visitors gathered in December 2020 to celebrate Hanukkah. Guests of honor inside the dimly lit stone archway of the Western Wall Tunnels in Jerusalem included a who’s who of Jewish officials from the Trump administration, including White House advisors Jared Kushner and Avi Berkowitz, and U.S. Ambassador to Israel David Friedman.

Together, the group lit the candles, recited the blessings and sang Hanukkah songs. Afterward, the rabbi of the Western Wall and Israel’s Holy Places, Rabbi Shmuel Rabinowitz, noticed a familiar face out of the corner of his eye. Rabinowitz proceeded with purpose, blowing past Kushner, Berkowitz and Friedman, to reach two-star U.S. Army Gen. Miguel Correa. The rabbi from Jerusalem and the general, a Catholic Puerto Rico native, embraced in a brotherly hug.

“‘What is this, you didn’t come over and give me a hug first?’” Correa recalled Kushner teasingly chiding Rabinowitz. But Kushner wasn’t the only one caught off guard by Correa’s warm relationship with the head rabbi of the Western Wall. As Correa recalled it: “Everybody was like, ‘What the hell?’”

Correa first met Rabinowitz a couple of months earlier, at a September dinner in Jerusalem celebrating the first commercial flight traveling from Bahrain to Israel following the normalization deal between the two countries in August 2020. Correa had since become an avid reader of the rabbi’s weekly newsletters on the Torah portion, something “I really looked forward to,” said Correa.

“My dad really drove all these cultures into our minds, and I think it helped me get where I’m at,” Correa told JI. “My parents had beat that into our heads, ‘Hey, what is going to be your contribution to this American experiment?’”

These visits to Jerusalem capped off an eventful year for the general, who joined the National Security Council early in 2020 and played a pivotal role in negotiating and bringing about the Abraham Accords, the agreements that saw Israel normalize ties with several Arab countries. Correa’s time in the White House followed a military career that spanned the Sinai Desert, Pakistan and the Alaskan wilderness, with stops along the way in Eastern Europe, South America and the United Arab Emirates.

It was in the UAE, where he was stationed for two years as a defense attaché, that Correa made the connections that would prove so fruitful to the negotiations between Israel, the UAE and the United States. But the seeds for his involvement in the back-channel talks were planted decades earlier, during a childhood that took him from a city near San Juan, Puerto Rico, to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he was called a “saltwater Mexican” when he hung out with other Spanish-speaking kids; to the arid desert heat of Kuwait, where Correa first learned Arabic and got to know people from across the Arab world, to the sticky humidity of South Florida, where, as a high school student, he met a Jewish person for the first time.

Correa in Jerusalem with senior American and Israeli officials, including former Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. (Courtesy)

The event in the Western Wall Tunnels was the general’s first time celebrating a Jewish holiday, but it fit neatly into his lifetime reverence for history and cultures vastly different from his own and an uncanny ability to fit in among people wholly unlike him. In fact, it was Correa who coined the name “Abraham Accords,” knitting together the three Abrahamic faiths — Judaism, Islam and Christianity.

“My dad really drove all these cultures into our minds, and I think it helped me get where I’m at,” the press-shy general explained to The Circuit / Jewish Insider at his home in Pompano Beach, Fla., in his first in-depth interview on his professional experiences and personal journey. Correa’s parents were the formative force in every career choice he made: “My parents had beat that into our heads, ‘Hey, what is going to be your contribution to this American experiment?’”

“He goes out of his way to understand us, to learn the culture, to learn the values,” Yousef Al Otaiba, the UAE’s ambassador to the U.S., said of Correa during a recent interview at the Emirati embassy in Washington. “He doesn’t just come in as an official who has talking points. And it’s not transactional. He actually really loves the culture.”

Understanding how Correa found himself in a position with access to the president of the United States and some of the most powerful leaders in the Persian Gulf requires looking back — at the culture of patriotism and exploration in which he was raised; at his distaste for bureaucracy and process, which led to a major career setback just before his time in the White House; and at his ability to make a friend of just about anyone, a gift he inherited from his father.

*****

On the Tuesday before Thanksgiving, Correa, 54, was the picture of relaxation. He had moved to Pompano Beach, just north of Fort Lauderdale, after retiring from the military in October. Life after the military seemed to suit him: He wore khaki shorts and a T-shirt from his alma mater, the University of Florida. Aside from a crew cut, good posture and a strong, stocky build, nothing about Correa clued you into his years spent in special-ops.

Correa’s living room looked like it belonged on the cover of a Jimmy Buffett album. On the wall were several tchotchkes and signs from bars in the Florida Keys, where he first met his wife. A bowl of painted seashells sat on the coffee table; a branded Margaritaville blender was on the counter. Against the wall was a tiki-themed bar, and above it, the room’s only relic of Correa’s decades in public service: A framed photograph showing Correa, former President Donald Trump and the other U.S. officials involved with negotiating the Abraham Accords. All held up two fingers, flashing a peace sign. Below the photograph was the pen Trump used to sign the agreement selling F-35 fighter jets to the UAE (a deal that was adjacent to but not technically part of the Abraham Accords).

“Whoever thought, in my life, that this one short Puerto Rican would be sitting in the Oval on a historic moment?” Correa asked, with a bemused sense of wonder about the fact that a boricua like him made it all the way to the White House. He has returned to this question at each major accomplishment or turning point in his life, constantly taking stock of how far he and his family have come from their Caribbean birthplace.

In the first of several conversations with JI, Correa alternated between detailed reminiscences of his time in the White House and scenes from his childhood, peppered with centuries-long history lessons on topics ranging from the Palmach Jewish fighting brigade in Mandatory Palestine to the Gulf royal families.

Read the rest of the story on The Circuit.

The Circuit is our new sister publication covering the Middle East and beyond through a business and cultural lens.