Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Joe Lieberman still walks the center path

The former Connecticut senator has released a new book urging a ‘centrist solution’

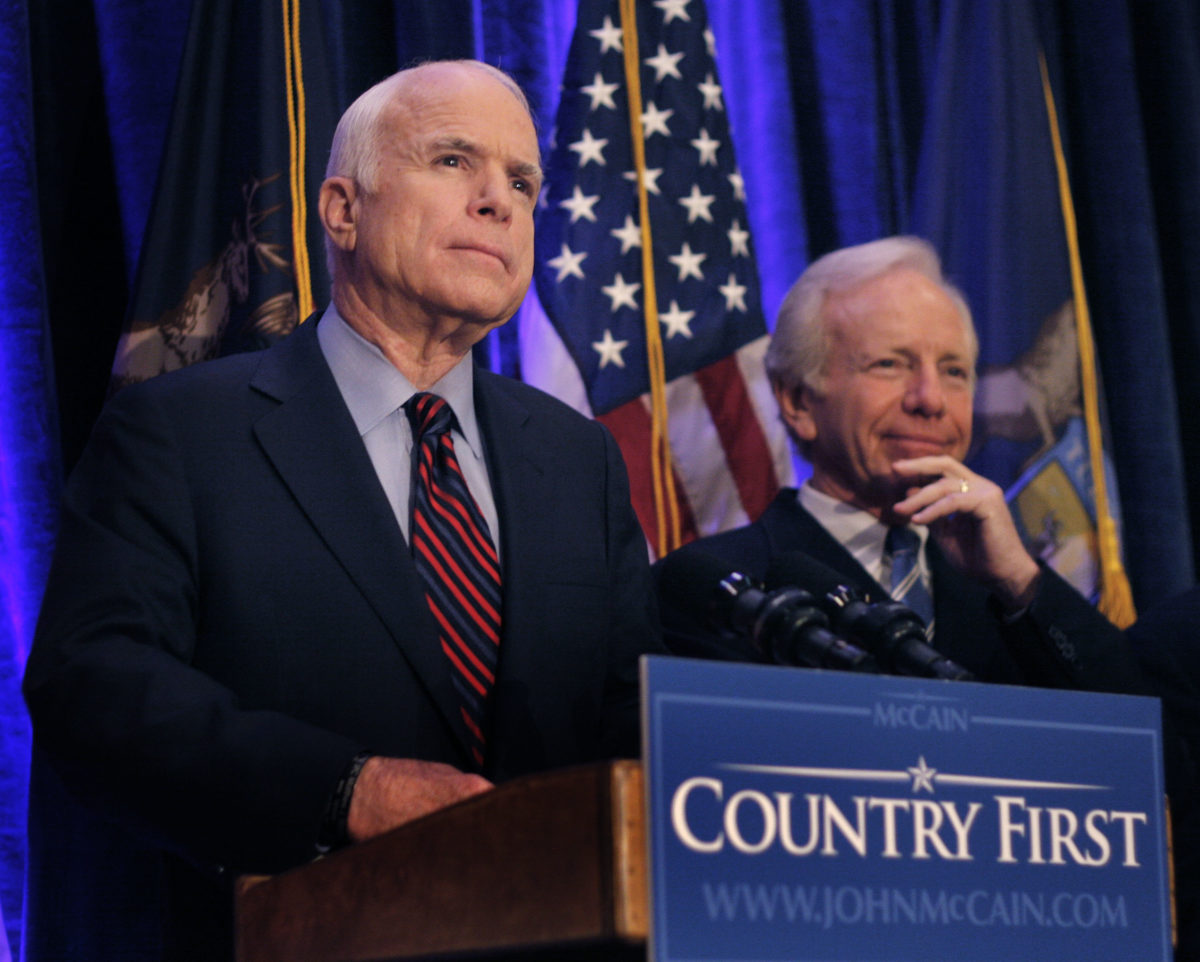

For more than two decades, former Sen. Joseph Lieberman (I-CT) was among the most moderate of U.S. senators. This centrist streak brought him to the brink of the White House as the Democratic vice presidential nominee in 2000. After losing the Senate primary six years later, he angered Democrats by running in — and winning — the general election as an Independent. Two years later, he endorsed Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) for president in a move he hoped would strike a tone of bipartisanship. The endorsement backfired, earning him criticisms of betrayal from many in the Democratic Party, and setting up an unusual dynamic of a senior party member who was feted on the convention stage only eight years earlier suddenly looked upon with distrust.

Still, Lieberman stands by his centrist political decisions. Now he wants to encourage more politicians to do the same. His latest book, The Centrist Solution: How We Made Government Work and Can Make It Work Again, serves as a call to action for politicians to seek a more collegial middle path towards governance. “I always try to distinguish between centrism as not the same as moderation,” Lieberman explained in an interview with Jewish Insider. “Centrism is a strategy, moderation is an ideology. Centrism involves left, right, Republican, Democrat, Independent, moderate, coming to the center and working together to try to find a solution to a problem.”

His book — part memoir, part political manifesto — chronicles what Lieberman argues are the essential qualities of good government. While the last years of his political career offered a stark warning about the political dangers of fully embracing bipartisanship, Lieberman hopes that his legacy can inspire a new generation of centrist politicians.

The following interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Jewish Insider: You credit your Judaism and your study of the Talmud as guiding your political beliefs. You write, “the Talmudic ethic is an ideal precondition for centrism and problem solving politics.” How important is religion in developing a centrist worldview?

Joe Lieberman: As I look back at my own personal history, about the various forces and ideas that were at work on me over my life, it did seem to me that my Jewish upbringing, and particularly the Talmud, was really an important part of how I became a centrist. I don’t think I felt that as I was getting into politics. I always say that my religious upbringing, the whole ethic of tikkun olam, or kiddush hashem, was part of what moved me into public service. But when I looked back at the whole development of Jewish law, of the Talmud, [it] resulted from spirited, respectful discussion and argument. And then, more often than not, agreement on a course to go forward, and rarely ended up in the kind of personal animosity.

JI: Do you think this is unique to Judaism?

JL: In the brief section about the origins of centrism, I point back to the Greek philosophers, and then particularly speak of sentiments in Judaism and Christianity, which really talk about the importance of the “golden mean of moderation.” I quote people like Rambam and St. Thomas Aquinas. But I think that Judaism is unique in the development of our comprehensive and detailed system of law, which emerges from discussion and dispute and resolution by rabbis and scholars. I do think in that sense, Judaism is unique. In other words, the other great religions also favor middle centrism; say that wisdom is often found in the center — ‘not too hot, not too cold’ is the metaphor that I use. But I think Judaism is different in the way in which Jewish law has been developed.

JI: You have obviously been around many politicians in your life. Do you find that having a religious background or having religious belief is useful in developing a centrist point of view? To put it another way, is a politician who is religious more likely to be moderate or centrist?

JL: That’s a really interesting question. I don’t know if anybody has ever asked me that before. I can’t say that was the case. In other words, there are people I’ve served with in state and federal government who are quite religious, but they were liberal, conservative or centrist. But I did find something else — it’s a different way I want to distinguish it: Part of what I try to say in the book, and I’ll stress now is that to come to the center and negotiate with people who don’t feel exactly the way you do about an issue requires you to have some kind of trust in the other person or other people. And part of that trust is getting to know those people. For instance, John McCain and I got to know each other a lot because we traveled so much around the world, particularly to visit our troops, but also to visit different countries and leaders. So we trusted each other, even though we disagreed on a lot of things. And we became very good friends, and often successful legislative partners. And I do think, as I say in this book and I’ve written elsewhere, that the fact that I became known as a religiously observant Jew was a source of respect, perhaps trust, from my colleagues, particularly during my years in the Senate, when my religious observance became more public.

JI: In your book, you argue that the majority of Americans still remain moderate in their tastes and in their political interests. Yet, clearly, there’s been a rise in the election of partisan politicians over the last decade. Why is that? If the voters want centrist problem-solvers, why are these partisan politicians winning instead?

JL: The reason is that the centrists, the independents, the moderates, are not as intensely involved in the selection of nominees for Democratic and Republican parties for Congress and other offices. And that allows the further left and further right of the two major parties to have disproportionate influence on who’s chosen.

One question that is periodically asked in polls is, “Do you want your elected representative in Washington to keep every promise that he or she made about what they’ll do in the last campaign? Or do you want them to negotiate with people in the other party or different point of view to get something done?” It’s always the latter that gets the strong majority of support, which makes sense, of course. But that’s not being reflected in office for other reasons: gerrymandering, money, partisan media, power of the parties controlling money, etc. To take the most handy example, a big reason why Joe Biden was elected our president is because people felt that his background record would be a unifier, [that] he would bring people to the center around him to get something done.

Usually, the American political system is dynamic and moving and reflecting what the people in the country are experiencing, which is a time of remarkable change economically where people are insecure in terms of their economic future because of technology and also because of the tremendous cultural changes which [because of] labor and demographic changes, leave a lot of millions of Americans feeling that they may be on the outside in the future. So they express this insecurity and even anger through the political system, and it really calls on leaders, challenges leaders in both parties to respond to those public emotions in a way that is ultimately unifying rather than divisive, which, unfortunately, today, it seems to be more often than not.

JI: You write of your 2006 Senate reelection: “Was one of the lessons learned in my 2006 Senate campaign that third parties are a good way to disrupt the partisan duopoly of Democrats and Republicans that has stymied our government? American history (past and recent) doesn’t support that conclusion. I was lucky that Connecticut is one of a minority of states that allows a candidate who has lost a party primary to run as an Independent. In most of the states, the two major parties have foreclosed that second chance by law.” How should states create more opportunities for serious Independent or third-party runs?

JL: A lot of this book, The Centrist Solution, is about people of different ideologies coming together and negotiating in the spirit that Talmudic scholars and rabbis have done for centuries. The reality is that the two parties, in addition to ideology, are also divisive now. The fascinating thing to me is that the two parties have assumed a powerful reality in American politics which is not required by the Constitution or the law. Once they settled into a two-party system, the two parties inevitably did things to protect their duopoly. So they’ve made it harder for third-party candidates. I think this is so pervasive a two-party system, that this book and a lot of my effort both in Congress and since, through this organization No Labels, which I chair, has been to encourage, first, the nomination and election of Republicans and Democrats who will be centrist and therefore give us a higher hope that something will actually get done by our government in Washington. But I also think that, if that doesn’t work, and the two parties cannot become more centrist in the way that I mean it, of working together and bipartisan, then it ought to be easier for people to form third parties.

Most states, if you lose a nomination and a primary or a convention, you can’t run after as an Independent. In many states, it’s quite hard to run as an Independent because you have to get a large number of signatures. And let’s go to the presidential level, it is very hard to qualify as a third-party candidate in enough states to have a plausible chance of actually getting elected.

JI: Should more candidates who have lost primaries run as Independents?

JL: I think they should have the right to do it. Now, whether they do, or whether they can win, that’s a different story.

JI: Were you shocked by the reaction you got from Democratic colleagues when you ran as an Independent?

Presumptive Republican presidential nominee, U.S. Senator John McCain (R-AZ) (L) speaks with the news media at a press conference as Sen. Joseph Lieberman (I-CT) listens August 13, 2008 in Birmingham, Michigan.

JL: What was really hurtful to me was the reaction. This was more of Democrats in Connecticut, because during the primary most of the Democrats who I served with in the Senate stuck with me.

I talk about one of the unions, the International Association of Machinists, representing the workers at Pratt and Whitney, an aircraft engine company. I’d worked very hard and really produced a lot for them as workers, but also, I think, for the country and our security. And I’ll never forget, as I described in the book, the head of the union in Connecticut called me up and said, “This is one of the hardest calls that I’ve ever made, but our union is going to endorse your opponent in the primary. We really appreciate everything you’ve done for us, Joe, but our national union just told us they don’t agree with you on the Iraq War, therefore, we can’t support you.” [Lieberman backed the war.]

But you get over it, you go on. I was lucky enough to have an opportunity under Connecticut law to run as an Independent. And of course, when I won as an Independent, it was probably the most gratifying, thrilling moment of my electoral career, just because I essentially came back from defeat, thanks to the voters in Connecticut.

JI: You write that in 2008, neither then-Senators Hillary Clinton nor Barack Obama asked for your endorsement, whereas Sen. McCain, who you endorsed, obviously did. Had they asked, would you have considered giving your support?

JL: Yeah, I definitely would have. I met Bill and Hillary Clinton when they were at law school in the early ‘70s. I had graduated a couple years before, but I started practicing law in New Haven. Bill Clinton helped me in my first campaign for state senator in 1970. And so I was an early supporter of President Clinton in the ‘92 campaign. I worked with Hillary. We knew each other well. And when Barack Obama got elected in 2004, as I say, in the book, the Senate had a program which encouraged more bipartisanship where they urged, in some sense, required, incoming senators, to choose two incumbents as mentors, one of each party. I was surprised and honored that Barack Obama chose me as his Democratic mentor. So we got to know each other pretty well. It would have seemed natural for either Clinton or Obama to ask me to support them. They never did. And I understood it, because the [Iraq] war in 2008 continued to be a deeply divisive issue.

There was such a prevailing consensus in the Democratic Party, particularly among voters who voted in primaries, that the war was a terrible mistake. The fact that I had been unwilling to give up on it until I felt we had stabilized the country — which, in fact, by 2008 we had — made me persona non grata among a lot of Democratic primary voters.

I assume that’s why Hillary and Barack didn’t ask for my support. But it would have been natural. It would have been a hard decision between them because, as I said, I had close relations with both of them. But it would have been more natural for me to support Clinton or Obama than for me to support McCain. But by the time John asked me, around November of 2007, it was clear to me that Obama and Clinton were not going to ask for my support. And also, I loved John, I believed in John, I trusted John. And I knew he was ready to be president of the United States on day one. So I also felt that I was making a statement about bipartisanship. I was still a Democrat that was elected as an Independent, registered Democrat. And obviously he was Republican, but this is what I think is best for the country.

JI: Do you think that came across as a statement of bipartisanship or was it seen more as a move to the right?

JL: I don’t know. It’s possible. But McCain was such a maverick still, and it was seen that way by a lot of people, including Republicans, that I don’t think it was seen as a move to the right. It was probably seen as an expression of our friendship, which had been much written about by that time. But also, I know, among Democrats particularly — again, I’ll use the term Democratic primary voters — it was seen as yet another indication that I was really, in their mind, not a good Democrat. And so in that sense, it had an effect.

JI: Going back to President Biden, you write in the book, “the only way we will solve some of our serious national problems and seize some of our great national opportunities… will require Republican members of Congress to break away from Trump, and it will require Biden and Democratic members of Congress to declare their independence from far-left Democrats who won’t compromise.” Centrist Democrats have reportedly grown annoyed by President Biden’s refusal to take a hardline stance in negotiating with progressives on the infrastructure bill. How do you assess President Biden’s strategy?

JL: I mean, there has to be room and there is room in the Democratic Party for what I would call center-left Democrats like Joe Biden. That center-left group is probably the majority in the Democratic Party. I would never say to exclude the further-left Democrats who don’t want to compromise, but they can’t be allowed to think that they can control the party, or the president of the party. They don’t have the numbers to justify that. There have been times, I will say, in the months since President Biden was elected that I felt that the “Squad,” the so-called “Progressive Caucus” in the House, has had more influence in the party and in the Biden administration than they’re entitled to. Again, I would never exclude them, but they have to come to the center also and begin to negotiate.

It appears, I say with some hope, now that that’s happening, that they all had to understand that the $3.5 trillion bill was just more than our country could afford and more than could be accomplished politically. Some of the centrists — in the Senate, [Joe] Manchin and [Krysten] Sinema; in the House, Josh Gottheimer and all the Democrats — who said “Stop, whoa, take a step back” [are] having an effect… Some of the programs, in my opinion, have so far not been well thought-out or well-discussed in Congress. It’s gonna lead to tremendous Democratic defeats in the congressional elections next year, and perhaps in the presidential election in 2024.