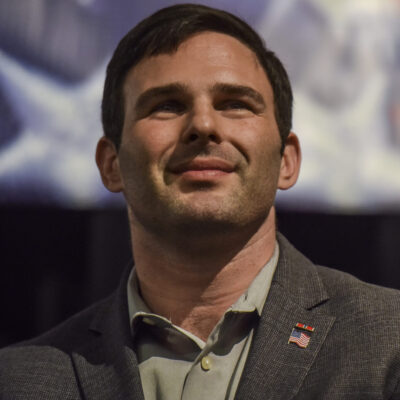

Michael Hickey/Getty Images

Kevin Warren’s big tent

The sports executive has leveraged his position to promote diversity, equality and inclusion while raising awareness of antisemitism, racism and other forms of bigotry

Last March, Kevin Warren, the powerful commissioner of the Big Ten Conference, took a moment from his demanding schedule to congratulate Yeshiva University’s men’s basketball team after the end of a historic season.

The small but mighty Maccabees had drawn national headlines for racking up a stunning 50-game winning streak and bagging a conference title while en route to a highly anticipated Division III tournament game that would ultimately end in defeat.

To Warren, the achievements of the regular season were an inspiring testament to “the wonderful influence the Maccabees have had on our nation and the Jewish community,” he wrote in a heartfelt letter to Elliot Steinmetz, the head coach. “As your team uniquely appreciates,” he went on, “so much of life is bashert — predestined and connected through God.”

The Yiddish term, as it happens, is particularly resonant for Warren, who holds a personal connection with the Jewish experience that extends back to his childhood and now animates a professional dedication to promoting social justice initiatives. “I heard the word bashert years ago, and it was so apropos for so many periods of my life,” he explained in a series of interviews with Jewish Insider this fall. “It has great meaning to me.”

As the first Black commissioner of a Power Five conference, Warren, 59, has received plaudits for his business acumen since he assumed leadership of the Big Ten in 2019, after years with the NFL. His most high-profile feat came this past August, when the former lawyer negotiated a TV deal worth more than $7 billion over seven years that divided football games among three leading broadcast networks, setting a record for college athletics while shattering the league’s previous agreement.

But the groundbreaking sports executive, who is based in Chicago, has also leveraged his position to promote diversity, equality and inclusion while raising awareness of antisemitism, racism and other forms of bigotry on college campuses and beyond. Last year, for instance, he formed an ongoing commission to address bias and hate amid an uptick in anti-Jewish incidents, enlisting the Anti-Defamation League to provide commission members with training and education.”

“One of the things I’ve been really struck by in conversations with Kevin is he recognizes the platform that he has, he recognizes the responsibility that comes with the role, and he blends that with his personal commitment,” said David Goldenberg, the ADL’s Midwest regional director, who is actively involved with the program.

The feeling is mutual. “Anything the Big Ten Conference can do to eradicate hate on our campuses and in our communities, in society, we’re all in, and the Anti-Defamation League has just done such great work in that area,” said Warren, who established the Big Ten Equality Coalition in 2020 to build on that effort. “The platform here has afforded us the opportunity to move the dial.”

“He was very much always counseling us to share our stories,” Wilf said of his former charge, recalling that Warren had encouraged him to speak openly with players and employees about Wilf’s relationship to the Holocaust as the Jewish son of survivors. “He’s promoted so much in the areas of diversity and tolerance,” Wilf told JI.

Such activism has long been central to Warren’s involvement in sports and dates back at least to his tenure working for the Minnesota Vikings, which has collaborated with the ADL. During the 15 years he spent with the team, Warren, who had previously held positions with the St. Louis Rams and the Detroit Lions, became the NFL’s first Black chief operating officer as well as the league’s highest-ranking Black executive. He also developed a close relationship with the Wilf family, which owns the Vikings and whose surname graces Yeshiva University’s main campus.

In 2019, shortly before he moved on to the Big Ten, Warren was among a group of Vikings staff members who participated in what he described as an “emotional” visit to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., with Mark Wilf, the team’s president and co-owner, and a former chair of the Jewish Federations of North America.

“He was very much always counseling us to share our stories,” Wilf said of his former charge, recalling that Warren had encouraged him to speak openly with players and employees about Wilf’s relationship to the Holocaust as the Jewish son of survivors. “He’s promoted so much in the areas of diversity and tolerance,” Wilf told JI. “He’s been a leader on all of those fronts.”

The horrors of the Holocaust have also loomed large throughout Warren’s life. Growing up in Phoenix, he said, his late father, a veteran of World War II, would often recount his experiences witnessing firsthand the concentration camps in Germany and Poland. “He had pictures from Auschwitz and Buchenwald, and he would show us those pictures,” Warren told JI. “They just forever resonated in my mind and my heart and soul.”

“There were many nights that it troubled my spirits so much I couldn’t even sleep as a young boy,” he remembered.

Years later, he said, the lessons his father sought to impart have continued to guide him. “He spent a lot of time talking to me and my siblings about the Holocaust and for us to make sure we do our part in the world to never let these types of just horrific events ever happen again,” Warren said. “Whether it’s slavery, whether it’s the Holocaust, whether it’s the mistreatment of certain classes of people — just to stand up and protect those who need protecting, and to amplify not only our voice but our actions.”

“I just always want to make sure that I do everything I possibly can for anyone who has faced obstacles,” he told JI. “To make sure that I’m doing my part individually, my family’s doing our part, the companies where I work, that we’re doing our part to make sure that we identify all of these issues and make the world a better place for people and create equality.”

On an interpersonal level, Warren is both “fearlessly” and “fiercely inclusive,” said Adam Neuman, the chief of staff, strategy and operations and the deputy general counsel for the Big Ten.

Neuman, who is an Orthodox Jew, said the commissioner has always demonstrated an unusual level of sensitivity to his observance of Shabbat as well as kosher dietary laws, among other things. He even keeps the Jewish holidays on his calendar. “We’ve had meaningful dialogue on Judaism and Jewish principles,” Neuman said. “For him to go out of his way to be so inclusive to others, I think, creates an incredible work life for employees,” he told JI. “I think that’s why you’ve seen so much business success.”

“With Adam, so many people told me — and I think told him — that he wouldn’t be able to work in college athletics because he observes the Sabbath from sundown on Friday to sundown on Saturday, and I think we’ve proven that wrong,” Warren said. “I just have great respect for every person that places their faith as a top priority and remains disciplined.”

Warren, a Christian who counts Emanuel Cleaver as one of his former pastors, describes himself as a man of faith. “My faith is very paramount to my existence,” he said, “and I really have made it a point so that we can build bridges between the Black community and the Jewish community.”

This summer, Warren led a group of student athletes and Big Ten staffers on a civil rights pilgrimage to Selma and Montgomery, Ala., in the first of a planned series of trips that are meant “to inspire a meaningful dialogue about racial, social, religious and cultural injustices in our nation,” he announced at the time. “Part of the collegiate educational experience not only occurs in the classroom” or “on the playing field,” he told JI. “It occurs in the community.”

“To be able to spend time in Montgomery, Alabama, was just a powerful educational experience,” Warren elaborated. “To walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge and understand that he was a former Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan and all the issues that people have faced — individuals from white to Black to Jewish to young people who came during that time of crisis in our country.”

As he comes upon his fourth year as commissioner, Warren said he is eager “to continually amplify and fortify” such initiatives at the helm of a historic and potentially far-reaching institution like the Big Ten, the oldest Division I athletic conference in the U.S.

His dedication is perhaps best encapsulated in another oft-used Yiddish term that he regards as especially aspirational. “Mensch is a powerful word to me,” he told JI. “I strive every day that people refer to me as a mensch.”