Gabby Deutch

In new museum exhibit, a rare journey into Samaritan life and religious practice

The exhibition, on display at Washington’s Museum of the Bible through the end of the year, offers an interactive glimpse at life for the 850 Samaritans living in Israel and the West Bank

Next month, as the leaves begin to change colors and the air turns crisp, Jews around the world will gather in makeshift huts for Sukkot, a holiday celebrating the fall harvest. The sukkah, or booth, built by each family will follow the same guidelines: three walls, with one side open; and a roof, partly open to the sky, made of plants like branches or palm fronds.

In two tiny corners of Israel and the West Bank, another Sukkot will be observed — a familiar but somehow different celebration, one that is marked indoors due to fear a millennia-old fear of persecution, under colorful roofs adorned with fruits of every variety.

This is the Sukkot celebrated by the Samaritans, an ancient Israelite religious group whose members number just 850, split between Holon, near Tel Aviv, and Nablus, a Palestinian city in the West Bank. Visitors to “Samaritans: A Biblical People,” a new exhibit at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., can sit under a replica Samaritan sukkah, decorated with more than 1,800 pieces of plastic fruit in a rainbow array of concentric circles.

“Everyone’s heard of the ‘good Samaritan,’ of course, or just the New Testament story,” said Jesse Abelman, the museum’s curator of Hebraica and Judaica. “They go back farther than that. They see themselves as the descendants of the biblical tribes of Ephraim and Menashe, and so they’ve been continuing their tradition sort of beside, parallel, to Jews.”

A replica of a Samaritan sukkah at the Museum of the Bible (Photo: Gabby Deutch)

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines a good Samaritan as “one who voluntarily renders aid to another in distress although under no duty to do so,” and suicide-prevention charities around the world bear the name “Samaritans.” But the notion of a good Samaritan comes from a parable in the Book of Luke, in the New Testament. Jesus tells of a man who was on the road from Jerusalem to Jericho, who was attacked and left for dead. A priest passed him by, and then a Levite, before a Samaritan — a member of a religious group viewed by Jews, Christians and Muslims alike as outsiders — stopped to help him.

“I try not to interpret New Testament passages for people,” Abelman, who earned his doctorate at Yeshiva University, joked. “But I think the basic point is clear, that you shouldn’t reject people out of hand, but that they may actually be the person who best embodies your values.”

On an exclusive tour previewing the exhibit last week, Abelman pointed out some of the unique artifacts on display, like a centuries-old mosaic from a Samaritan synagogue and a stone with an inscription of the Samaritans’ Ten Commandments, on loan from Israeli President Isaac Herzog. The exhibit, which runs through the end of the year, is meant to educate visitors about Samaritans and their encounters with other monotheistic religions over the past 2,000 years.

It is the museum’s first partnership with Yeshiva University, which helped curate the exhibit through its Center for Israel Studies. The museum, which opened in 2017, has close ties to the evangelical Christian community through its founder and board chair Steve Green, the president of Hobby Lobby. But it has made efforts in recent years to broaden its reach into other religious communities.

The museum has also faced controversy over the provenance of some of its artifacts. In 2020, the museum returned thousands of objects to Iraq after discovering that they had been looted, three years after the Green family was forced to turn over thousands of other artifacts from its personal collection — and pay a $3 million fine — for the same reason. Also in 2020, independent researchers confirmed that 16 Dead Sea Scroll fragments in the museum’s collection are modern forgeries. The permanent exhibition where those fragments appeared still displays the now clearly-marked forgeries, while also offering insight into how experts figured out the fragments were not authentic.

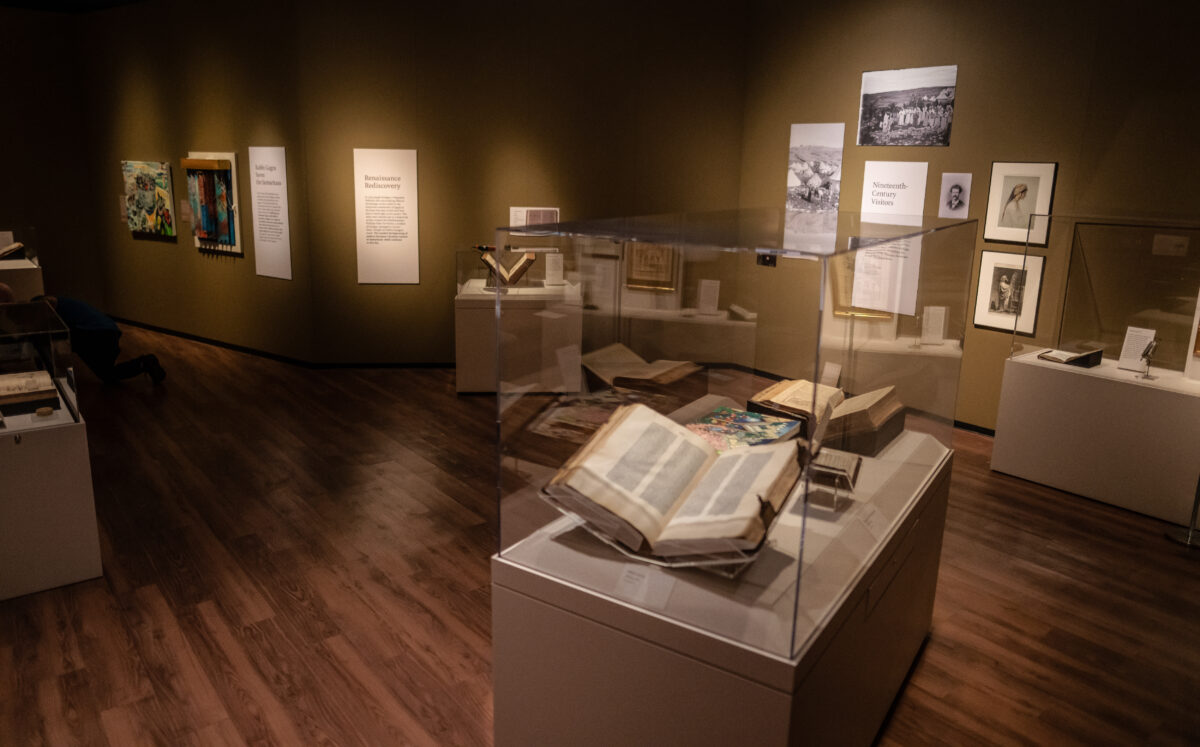

Samaritan exhibition at the Museum of the Bible (Photo: Gabby Deutch)

Like Jews, the Samaritans are descended from the Israelites. Their religion is similar to Judaism — they also read a version of the Torah, and use a form of ancient Hebrew with different letters — but one of the biggest differences is that they still conduct animal sacrifices, a ritual that is explained in videos and photographs at the museum. The exhibit also makes other comparisons between the faiths, such as one display case where a Samaritan Torah and a Jewish Torah are placed next to each other to show the difference in calligraphy and style.

In the Samaritans’ origin story, when Jews went to Jerusalem to build the Temple, the Israelites stayed at the foot of Mount Gerizim, the mountain where they believe the biblical story of the binding of Isaac occurred (and not Mount Moriah, which is where that occurred according to Jewish tradition). “None of this happened, according to the Jewish side of the story,” Abelman said. “And so there was, historically, conflict: Who really holds the proper Israelite tradition?”

Samaritans were historically regarded as suspect by Jews, and here Abelman pointed to a famous travelog by Benjamin of Tudela, who was born in what is now Spain in the 12th century. Abelman traveled to the Middle East and encountered the many people — including Jews and Samaritans — who lived there.

“He says, ‘They all basically get along. The Jews don’t marry the Samaritans, but they basically get along,’” said Abelman. “At the same time, he also repeats things about the stuff he thinks they get wrong. He ‘others’ them.”

Christians, too, were often intrigued by the Samaritans, given the prominence of the “Good Samaritan” parable. At the turn of the 20th century, as the Samaritans’ numbers dwindled and many lived in poverty, they sold artifacts to collectors, usually Protestants. This sparked worldwide interest. In the museum’s exhibit, one display case shows in-depth magazine feature stories — one in National Geographic in the 1920s, and another in LIFE in the 1950s (alongside a large Kool-Aid ad) — about Samaritan rituals. (Twenty-seven different institutions from around the world lent objects, letters and artifacts to the Museum of the Bible for the exhibit.)

The exhibit explains the Samaritans’ history, and how the group expanded around the Eastern Mediterranean, to places such as Greece and Syria. At the time the Mishnah, a major rabbinic work, was written, the Samaritans were the largest ethnic group in the region which is why they appear in that Jewish text.

The Samaritan exhibition at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C. (Photo: Gabby Deutch)

But they were killed in large numbers after rebelling against the Byzantines, and today less than 1,000 remain. Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, the second president of Israel, helped mend ties between Jews and Samaritans after he came to Ottoman-era Palestine in the early 20th century to learn Hebrew and accidentally ended up in the home of a Samaritan family, rather than a Jewish family.

“The relationship with the president’s office has been important to the Samaritans in terms of their relationship with the State of Israel and Jews more broadly,” said Abelman. “That has really helped to repair, like, thousands of years of — if not outright animosity, at least dislike and distrust and ambivalence.”

The museum also features several short films that take visitors into the homes of Samaritans, people who today are mostly assimilated into modern life in Israel and in the Palestinian territories. (Samaritans who live in Holon have special permission to go to Mount Gerizim, where religious ceremonies occur.)

“They’re really happy and excited to be able to have this exhibition take place and help tell their story,” said Abelman.

That’s how the museum always tries to “tell a story about another people,” said Rena Opert, the museum’s director of exhibits. “We would work with them and never presume to just make our own exhibit about a community that we don’t work with.”