Gabriele Holtermann-Gorden/Sipa USA via AP

Johnson-Lander rivalry heats up NYC comptroller race

New York City Council Speaker Corey Johnson and City Councilman Brad Lander are seen as the top contenders in the upcoming Democratic primary

Until recently, New York City’s comptroller race was a relatively staid affair, as a variety of candidates with little name recognition made their case for a position that, however consequential, is not well understood and difficult to pronounce.

Then, Corey Johnson jumped into the field. Johnson, the charismatic City Council speaker, had maintained something of a low profile since dropping out of New York City’s mayoral race last fall, attributing his decision to a depression he could not shake as the pandemic wore on.

But months later, he emerged reenergized, teasing his interest in the job before launching his campaign in early March — and instantly establishing himself as the presumed Democratic frontrunner. His late entrance dramatically reshuffled the political dynamic as Johnson siphoned off a slew of endorsements that would likely have gone to other leading contenders.

Perhaps no candidate has been more destabilized than Brad Lander, the progressive city councilman from Brooklyn who has been building his campaign for years. While Lander expected to earn an endorsement from Rep. Ritchie Torres (D-NY), the influential first-term Bronx congressman instead threw his support behind Johnson, and some council members later followed.

With just weeks remaining until the June 22 primary, Lander has pivoted to attack mode. The latest salvo from his campaign was a controversial website, released last week and titled “What’s the Story, Corey?,” alleging that the speaker “has passed very little meaningful legislation during this pandemic year to improve the lives of New Yorkers.”

New York City Councilman Brad Lander at a recent protest. (Courtesy)

“This is a critical time for New York City, and the comptroller has a vital role to play in our city’s recovery,” Naomi Dann, a spokeswoman for Lander’s campaign, told Jewish Insider in a fiery email on Tuesday evening. “Speaker Johnson has not shown up in the way New Yorkers needed during the crisis, is running for comptroller as a consolation and barely seems interested in the job.”

Johnson, who has rejected attacks that he is seeking the position as a consolation prize, was comparatively measured in a recent interview with JI. “The legislative process is complicated and it’s messy sometimes,” he said, seemingly wary of being dragged into a public back-and-forth. “But I’m proud of all the work that we’ve done.”

Still, Johnson couldn’t refrain from at least one sidelong insinuation. “Part of being a good legislator is being collegial and working with your colleagues, working with the chairs of respective committees,” he added. “That’s the work that I think all successful members do to actually see bills passed.”

The simmering rivalry, while dominating much of the coverage on the race, has also shone a spotlight on a position now carrying outsized importance as the city emerges from the ravages of a pandemic that has decimated New York’s social and economic fabric. The comptroller, who functions as the city’s chief financial officer, is responsible for a host of sweeping duties, including auditing city agencies, reviewing city contracts and overseeing five pension funds collectively valued at $250 billion.

Michelle Caruso-Cabrera on assignment for CNBC in Havana, Cuba in 2014. (Wikimedia)

The comptroller is a “potential ‘check’ on a mayor and the council,” according to Mitchell Moss, a professor of urban policy and planning at New York University. “It is a far more important job than being one of 51 City Council members who rename local streets.”

Though Johnson leads in recent polling — with Lander trailing by double digits in one survey placing him in second with 8% of the vote — the numbers suggest that the field remains competitive for several other candidates vying to break through in the crowded race to succeed Scott Stringer, who is running for mayor.

In interviews with JI, each candidate laid out their diverse qualifications for the job as well as an array of visions for the city, while all agreeing that the next comptroller will be uniquely poised to enact broad and meaningful change on the path to recovery.

“The stakes couldn’t be higher,” said Michelle Caruso-Cabrera, a former financial journalist who came in second behind Johnson in one recent poll. “The city has been shaken to its core.” Caruso-Cabrera, who mounted an unsuccessful campaign to unseat Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) last cycle, believes her experience analyzing financial documents as a CNBC anchor has prepared her to take over as the city’s top financial watchdog.

“My job,” she emphasized, “will be to follow the money and scrutinize every dollar.”

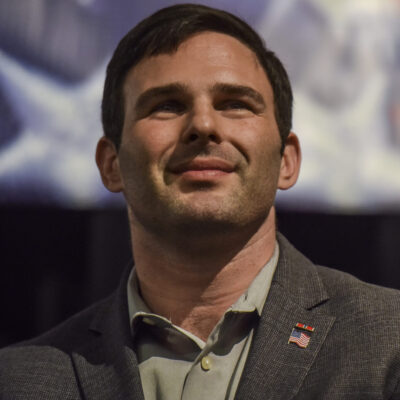

Zach Iscol at the Headstrong Gala. (Wikimedia Commons)

Zach Iscol is an entrepreneur and former Marine who initially ran for mayor but failed to gain traction, pivoting when he saw an opportunity in the comptroller’s race. “I think the only thing that this city needs in order to really rebound from COVID — the only ingredient that’s missing — is the right leadership,” he said.

“You don’t work for the mayor,” Iscol said of the comptroller job, noting that he will strive to reduce bureaucratic red tape for small businesses while establishing community banks throughout the five boroughs. “Your job is to make sure the city is doing its job for the people of the city, looking for waste, fraud, abuse and corruption.”

A trio of New York state legislators — including David Weprin, Brian Benjamin and Kevin Parker — fill out the roster of viable contenders.

“There’s a number of unique ideas that not only provide good returns for retirees but also deal with some of our social ills,” said Benjamin, a state senator from Harlem who touts his degrees from Brown University and Harvard Business School, emphasizing that he would use the comptroller’s seat to boost affordable housing as well as minority-owned entities through pension fund investments.

New York State Senator Kevin Parker meets with young students from Brooklyn at the Capitol Building in Albany (N.Y. Senate)

Parker, a state senator representing Brooklyn, said he would put “equity first” as comptroller, establishing what he described as an “economic equity council” and creating small business development centers for struggling communities.

“Having spent 10 years representing Borough Park, I’m really clear that small businesses are the backbone of the economy in Jewish communities all over the city of New York,” Parker said. “They’re going to need the same kind of access to capital.”

Weprin, an Orthodox Jewish assemblyman from Queens, boasts of his financial experience in the public and private sector. He pledged to open a comptroller’s office “in every borough” as part of his plan to provide a broader array of financial services to underserved businesses.

The state lawmaker, citing the comptroller’s fiduciary responsibilities, added that he would seek to increase pension fund investments in Israeli bonds, which he described as “one of the best investments that the city pension funds have made.”

New York City Councilman David Weprin speaking at City Hall. (Elbert Garcia)

Lander, who is Jewish, also committed to continuing investments in Israeli bonds as comptroller, despite supporting conditioned U.S. aid to Israel. “There’s a big difference between foreign policy and business or investment,” he told JI.

The councilman’s progressive policy agenda centers on an ambitious climate plan that he views as an urgent call to action. “Step one is to divest from fossil fuels as part of a much broader movement to demand change from financial institutions,” he said, adding that he would promote investments in renewable energy like rooftop solar production.

“I want to have a sustainability audit team that goes agency by agency for all our climate goals to make sure we’re holding the agencies to them, which right now we’re not,” said Lander. “We pass these really ambitious bills to require all our buildings to retrofit for energy efficiency, but that is going to take a lot of oversight or it’s not going to happen.”

Lander, who ran a nonprofit in Park Slope before he became a councilman, believes the comptroller’s office is well equipped for such tasks. “The next mayor will, whoever they are, want to do right on climate justice, but if you’re mayor, you wake up every morning to headlines, and those headlines are not about climate,” he told JI. “The comptroller’s supposed to take the long-term view.”

New York State Senator Brian Benjamin during Senate session at the N.Y. State Capitol in Albany. (N.Y. Senate)

In the thick of the election, though, Lander now appears to be thinking more incrementally as he positions himself as Johnson’s political bête noire. Over the past month, Lander has gained some momentum, having notched a coveted endorsement from Ocasio-Cortez in late March, followed by another from Jumaane Williams, the city’s public advocate and a stalwart in local progressive politics.

Still, it remains to be seen if such endorsements, coupled with a formidable war chest, will lend him the necessary boost he needs to gain an edge over Johnson and some other candidates in the race.

At the moment, Johnson appears to be the man to beat, despite having entered the race so late after dropping his mayoral bid because of mental health issues.

“I was very open and honest about the fact that I had been struggling at that time with depression,” Johnson recalled. “There were many people that told me not to be that open and honest, that it would hurt me in the future if I ever decided to run for office. But I came out when I was 16 years old in a small town. I was the only openly gay student in my entire high school. I’m the only openly HIV-positive elected official in the state of New York. I’m open about my sobriety and recovery.”

Johnson claimed that he hadn’t contemplated running for comptroller when he stepped back from campaign politics last year, but came to appreciate the urgency of the role after colleagues in the City Council suggested he consider it a few months ago. “I decided that I had the right skill set that matched with the office,” said Johnson, who released a policy agenda, “Do the Most Good: A Blueprint for NYC’s Recovery,” last week.

The blueprint touches on seven areas where Johnson has concluded the comptroller’s office can be most effective, including monitoring city agencies, protecting pensions and operating as a watchdog for federal aid as tens of billions of dollars in COVID-19 relief funds begin pouring into the city.

“I believe that at this pivotal moment in New York City right now,” Johnson said, “recovering and coming out of this pandemic, that this office, the comptroller’s office, is probably the most important office that no one is really paying attention to.”