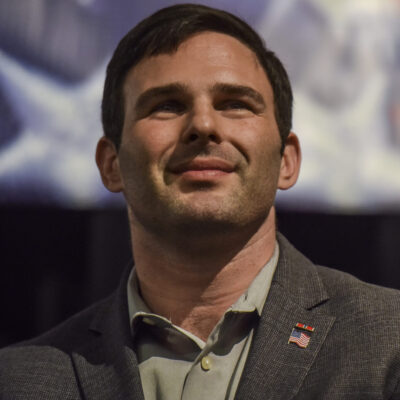

The USAID official pushing self-reliance as the highest level of ‘tzedakah’

Bonnie Glick said the agency is now focused solely on the global response to the coronavirus pandemic

Back in January, when it was still possible for public officials to work on things unrelated to the novel coronavirus, USAID was gearing up for a year of increased outreach and cooperation with the private sector. For Deputy Administrator Bonnie Glick — who has held the No. 2 post at the U.S. Agency for International Development since early last year — tightening the bond between the government and the business community has been the guiding principle of her career, dating back to her days as an intern at the U.S. embassy in Moscow in 1989, just before the fall of the Iron Curtain.

But that was B.C. — “before coronavirus,” as Glick describes it. Now, USAID’s sole focus is the global response to the coronavirus pandemic, working in poorer parts of the world that have not yet been hit hard by the virus and in areas that have already been impacted but lack the capacity to do testing.

After the reported mismanagement of a shipment of personal protective equipment from USAID to Thailand, last week Vice President Mike Pence put a hold on all shipments of such gear overseas, saying it is needed in America first. This is an adjustment for USAID, which is used to handling outbreaks of diseases like Ebola and Zika in other countries — but not here in the U.S. “When I hear about docs and nurses in the United States having to reuse their masks and gowns, that is disheartening to me as an American,” Glick says. The order from the Trump administration to first dispatch this gear within the U.S. is meant “to help the international response while simultaneously protecting the home front,” Glick explains. “We can’t do anything to stop coronavirus if we’re not healthy ourselves.”

With missions in 111 countries and regions around the world, USAID’s two priorities are global development and disaster relief, akin to an “international FEMA.” But for Glick, whose three-decade career has included stints at the State Department, IBM, and an international development nonprofit, USAID does more than provide aid and assistance to developing nations around the world. It also spreads the distinctly American gospel of prosperity, self-reliance and free markets.

“There’s a little bit of a publicity or a PR campaign that we have to undertake,” Glick says, “going back to this concept of American generosity and America’s world leadership.” She is an adept spokesperson for the agency — rattling off data points and statistics about the $120 billion in global health assistance that USAID and the State Department have spent over the past 20 years to help dozens of countries fight diseases like tuberculosis, malaria, and polio — and for the role of the U.S. as a force for good in the world, a philosophy that has guided her since she worked in Moscow in 1989.

“I realized only then that U.S. universities” — Glick attended Cornell and Columbia and later earned an MBA at the University of Maryland — “had portrayed a vision of the Soviet Union as very different in my mind from what the actuality was,” she explains. “The Soviet Union was portrayed as a superpower, but from my time in the Soviet Union I saw that it was really just a developing country… with nuclear weapons, so it presented a real threat.” The lesson for Glick was that in this “very complicated world,” Washington is obligated to play a “moral leadership role.”

Glick attended Akiba-Schechter Jewish Day School, a “Conservadox” school on Chicago’s South Side where she learned Hebrew as a second language. Her sister, Caroline Glick, is a well-known conservative journalist in Israel who ran for the Knesset last year with Ayelet Shaked and Naftali Bennett’s New Right party, but failed to win a seat and chose not to run in the two subsequent elections.

With a grandfather who was a linguist and a mother who speaks four languages, Glick realized at a young age that languages came easy to her. Her decision to join the U.S. Foreign Service was “driven by a curiosity that I have about the world,” she says, even though the career move surprised many people in her community (she describes joining the Foreign Service as “the last thing that a nice Jewish girl would ever do”).

Her first posting as a Foreign Service Officer in 1990 was in Ethiopia, the first of two “recovering communist countries” – her term — where she was stationed. Ethiopia, like the Soviet Union, was just emerging from decades of communist rule that ravaged the country’s economy. “I went there in March of last year and saw a completely different country from the one that I left in 1993,” Glick says. As she sees it, the reason for the transformation is clear: Ethiopia chose democracy over communism. “To go from one of the poorest countries in the world to one of the fastest growing economies of the world is because the Ethiopians have reoriented themselves to the United States and away from communism,” she explains.

She accepted a post in Nicaragua next, where she moved with her husband, a fellow Foreign Service Officer. The two returned to Washington in 1998; the bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania did not contribute to a reassuring global climate for a pair of young diplomats raising a toddler.

A few years later, Glick left Foggy Bottom to work in international research and development at IBM. That, she explains, is where she developed her current worldview — about how industry is uniquely suited to “find great ways to apply technology and innovation” and better a country’s economy. And in January, when people were still planning for the year ahead as if it would be a normal one, Glick was preparing to push forward her plan to apply this ethos to USAID: “Engaging with both [the U.S.] private sector to show good business opportunities in emerging markets, and local private sectors to create sustainable environments for job creation, is what I focused on very heavily at the beginning of the year,” Glick says.

One way to promote more of a business mentality, Glick says, is by “changing the language around how we talk about the countries in which we operate.” So what the USAID might call a “developing country” would be considered an “emerging market” in the business community. USAID describes the people who live in those countries as “aid beneficiaries,” but in business they’re called consumers or clients. “No mother wants her child to be raised to be a refugee. She wants her child to be a consumer,” Glick explains.

Glick points to South Korea and Israel as countries that once received USAID assistance and are now major players on the global development stage. In August, USAID and its Israeli equivalent, Mashav, signed a memorandum of understanding to codify their work together. “They have a stellar reputation in terms of being able to help countries with water management, with agricultural production, and they are able to apply amazing Israeli technologies that we all know about from the startup nation,” Glick says. “It’s extremely gratifying to be able to work with them.”

Glick defended the Trump administration’s 2019 decision to cease USAID assistance to the Palestinian Territories, saying the Palestinians chose to give up USAID funding rather than giving up support for terrorism. “It actually isn’t controversial except it’s portrayed in a controversial way,” Glick says. “The Palestinians, through [Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud] Abbas, asked us to stop our assistance to the Palestinian Authority, because under congressional legislation it would’ve meant that they would be on the hook to pay reparations to American terror victims.”

In remarks at the recent signing of a memorandum of understanding between USAID and Mashav’s missions in Tbilisi, Georgia,

Glick said the relationship showed “the unique ways that democratic countries can help one another while also serving their own important political and economic priorities at home.” While her position has taken her to ceremonies like this all over the world, right now she — like millions of Americans — is working from home. Several days before Passover, this “plague all over the Earth” feels “almost biblical” to Glick. There are locusts in Africa, and illness around the world, and this, she says, makes USAID’s work more important than ever.

“I think that it comes down to Maimonides’s levels of tzedakah, with the highest level of his eight levels being exactly what we do at USAID,” Glick explains. “The highest level of giving is helping give a person the capability to fend for him or herself, and that is the story of self-reliance, and it’s what we do everyday and work toward at USAID.”