With a new book, Polish priest uncovers buried past of a Jewish community destroyed by Nazis

‘Chocz The Promised Land? The history of the Jewish community,’ spotlights a community that played a significant role in the town from the early 19th century until it was vanquished by the Holocaust

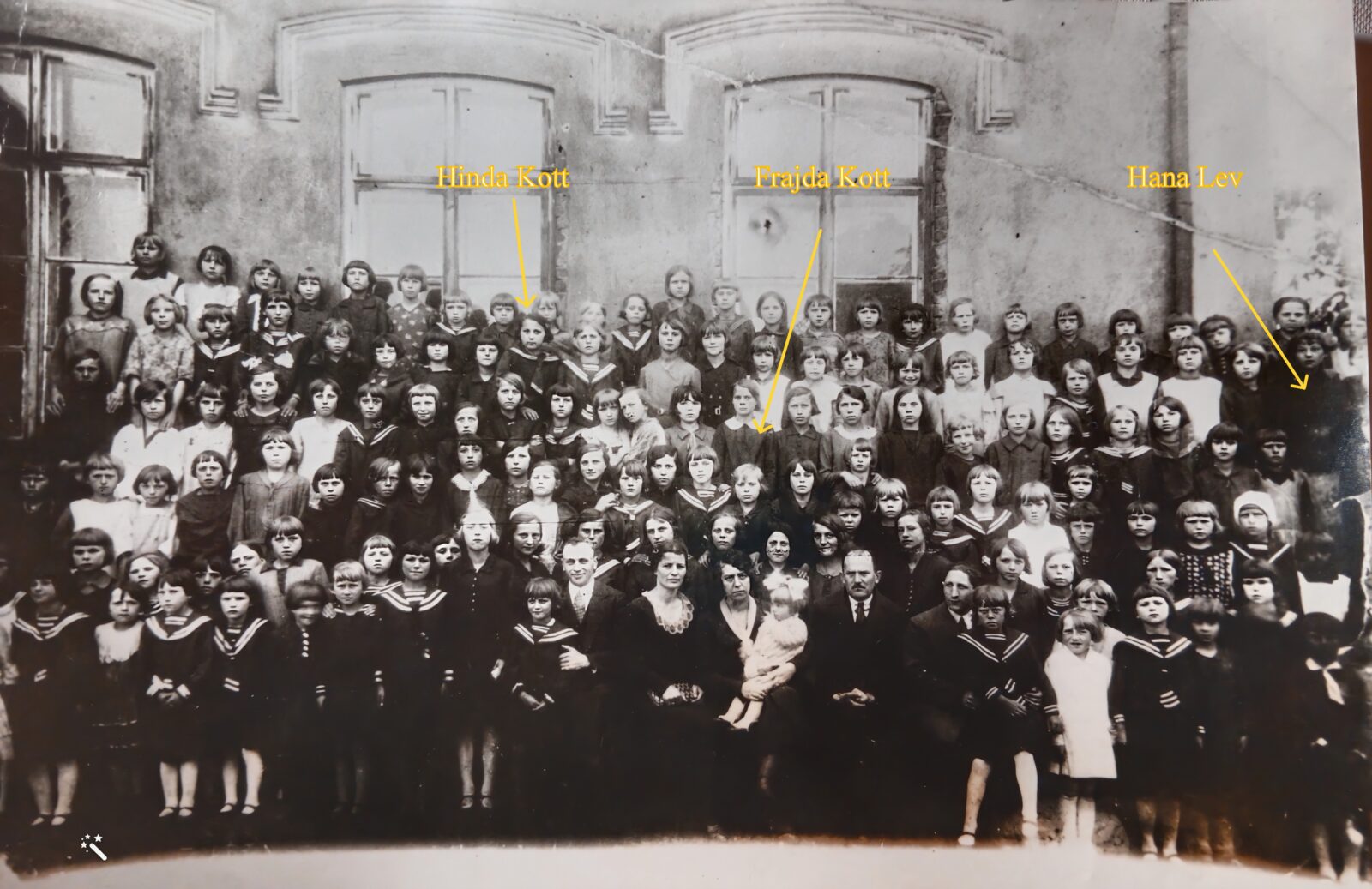

The grainy black-and-white photographs appear like classic yearbook pictures: Rows of young, elementary-school students — the girls in sailor dresses and the boys in blazers, all wearing dour expressions — are set against the soot-covered stone walls and casement windows of an old school building.

The unassuming photos, believed to have been taken sometime in 1936-1937, a few years before the Nazis rampaged through Poland, were from Chocz, a small town in central Poland. And when they ended up in the hands of a Polish Catholic priest who grew up in Chocz and was researching the town’s history for a book, the pictures — which were shot by a Jewish photographer and included two Jewish girls — launched Leszek Szkudlarek on a three-year-long journey that has illuminated the town’s long-buried Jewish history.

That research, carried out with the help of his former history teacher and the online genealogical site MyHeritage, forms the basis of Szkudlarek’s just-published book, Chocz The Promised Land? The history of the Jewish community.”

“My initial plan was that the Jewish people of Chocz would be just one chapter in the book,” said the priest, who admitted that he never knew Jews ever lived in his hometown. “But it was very interesting so I decided to write a whole book about the history of the town’s Jewish community.”

Szkudlarek’s project took a dramatic turn after he read an article in a local paper written by a woman who taught him history at school. The piece focused on a Jewish girl from Chocz who died in the Lodz Ghetto.

Up until that point Szkudlarek, a Catholic priest in the town of Paczków about 150 miles away, had no idea that Jewish people ever lived in Chocz, which is home to around 2,000 people.

He contacted the teacher, who went on to share more information with him — including the two school yearbook pictures that she said were “taken by the Jew Lewin.”

Intrigued, Szkudlarek then set about meticulously researching the identities of some of the individuals pictured in order to uncover the truth about the town’s Jewish community, which played a significant role in the town from the early 19th century until it was vanquished by the Holocaust.

The project, a labor of love undertaken during Szkudlarek’s private time, took around three years to complete. To collect information, he dug through archives and recorded testimonies and materials from residents, including one man who uncovered a collection of old Jewish books during a renovation of his attic.

But it was the photographs that proved crucial for his research. One of the pictures featured two Jewish children — Perla Jakubowicz and Abram Kluczkowski. The former perished in the Lodz Ghetto; Szkudlarek has still not uncovered the fate of Kluczkowski.

The second school photograph included three girls — Hinda and Frajda Kott and Hana Lev — who were all killed during the Holocaust, according to records he found through Yad Vashem.

Szkudlarek was researching the fate of the photographer, David Lewin.

Thanks to the extensive records and online family trees on the online genealogy site MyHeritage, he tracked down one of Lewin’s relatives: Sharon Stern, a 62-year-old retired psychologist from Tampa Bay, Fla.

Despite speaking no English, Szkudlarek reached out to Stern and discovered that her maternal grandmother, Tauba Edelsburg (nee Lewin), was born in Chocz in 1904. She was the photographer’s sister.

Through the website — and thanks to Google Translate — the pair spent some time corresponding. Stern sent Szkudlarek more photos taken by her great-uncle and of her family, while also connecting him to two of Lewin’s surviving children — a son in Israel and a daughter in Argentina, where the photographer settled after leaving Poland before World War II.

The information flowed both ways, as Stern also discovered new things about her own family through Szkudlarek — including the name and birth date of her grandmother’s sister who was shot and killed.

Stern told JI, “In going back and forth, Leszek said, ‘It would be my great honor if you would come back here for the book launch. I will pay for your accommodation, I will pay for your food’.”

Both of Stern’s parents were born in Poland and her father was a Holocaust survivor. As such, she had previously visited the country — but had never been to Chocz.

“I couldn’t say yes fast enough,” she said. “It was a dream come true.”

Szkudlarek brought his English-speaking nephew, Marek, along to translate, though they soon discovered that they both speak Spanish and could communicate directly through their shared language.

In a video call with JI and speaking through an interpreter, Szkudlarek said he had known “nothing at all” about the Jewish history of the town before reading the article by his former teacher.

That prompted him to delve into archives, uncovering the birth certificates of some of those in the pictures, as well as speaking to elderly residents of the town who still remember their Jewish peers.

He said the research he carried out on MyHeritage was the “key” that unlocked much of the buried past — while leading him to Stern and other relatives of those whose fates he was trying to uncover.

He was “very happy” that Stern took up his offer to visit Poland, because it was “very important to meet with her and for our community in Chocz.”

The book has been the subject of considerable local media interest, according to Szkudlarek, who said he has since been contacted by many people with new leads about the former Jewish community. He hopes to continue with his research and said it would be “his dream” to have his book translated into English.

Stern documented her journey in videos and photos of the packed itinerary that Szkudlarek had arranged for her — including a stop at an abandoned Jewish cemetery.

The book launch in March was held in the former fire station — now a cultural center — where the Jews of Chocz were rounded up by the Nazis and deported in the early 1940s.

While the fate of those who perished in the Holocaust cast a long shadow, Stern was heartened by the locals’ interest and enthusiasm. There was a standing-room-only crowd at the book launch, which featured music and speeches and displays of some of her great-uncle’s photography.

“My family, especially my father, didn’t have good things to say about the Poles,” said Stern.

“My trip was such a wonderful experience, and it definitely restored my faith in people. The Polish people were really warm to me.”

She added: “I have a lifelong friend in the priest and his nephew Marek.”

“My image of a priest is someone who is very staid and serious and he was anything but. He has a great sense of humor, he laughed a lot, it was absolutely wonderful.”

Naama Lanski, a researcher for MyHeritage, said that the meeting between Stern and the priest “embodies the power of family history research, which can lead to fascinating and completely unexpected connections between people.

“A Catholic priest from Poland who teams up with a Jewish woman from Florida, to tell the unknown story of an entire community, most of whom perished in the Holocaust. Such beautiful stories make us, again and again, happy and optimistic about the good that connects people.”