Courtesy

Serving faith and nation: The rabbis bringing light to U.S. troops on Europe’s front lines

Jewish military chaplains told JI about their drive to be ohr l’goyim, a light unto the nations

The women’s basketball team at Rochelle Zell Jewish High School in Chicago was practicing earlier this month ahead of its annual Senior Night when an announcement came over the intercom, presenting a special guest. That’s where the video starts — one of those designed-to-go-viral tearjerkers showing a child reuniting with their parent who is in the military.

“He is joining us after leaving the military service in Europe,” the announcer says. Team members start to look around, smiling but confused, when they see that the door to the gym is open.

“We are grateful for his dedication, especially his daughter Hannah,” the announcer continues. That’s when one athlete, in a long-sleeve practice jersey and a ponytail, begins to cry and run toward the door. “Thank you for your service and sacrifice, and welcome home, U.S. Army Chaplain Rabbi Aaron Melman.” Everyone cheers. Throwing her arms around her father, Hannah sobs.

Melman, a Conservative rabbi who since 2021 has served as a chaplain in the Illinois Army National Guard, had just returned from a U.S. Army base in Western Poland. He submitted his request for leave back in September but didn’t tell his daughter, who was devastated most of all to learn his deployment conflicted with the pinnacle of her high school basketball career. (She was more upset that he would miss that game than her graduation.) When she hugged him, Melman took off his cap and revealed a light brown yarmulke that matched his fatigues.

“We made it happen,” Melman tells his daughter in the video, smiling. Days later, RZJHS won at Senior Night. Hannah scored four points.

For more than two decades after he graduated from the Jewish Theological Seminary in 2002, Melman was a congregational rabbi in the northern suburbs of Chicago. He had thought, early in his career, about joining the military — his father served in the U.S. Army Reserves — but decided against enlisting, recognizing that serving in active duty would be challenging as he raised two young children.

But later, when his kids were older, the itch to serve returned. Melman was commissioned as an officer in the Illinois Army National Guard, a responsibility that typically required two days of service a month and two weeks each year, until he was sent to Poland earlier this year. That assignment made him one of several Jewish chaplains serving on the front lines of Europe, providing religious support and counseling to American soldiers — most of whom are not Jewish — who are stationed in Germany, Poland and other allied nations largely as a bulwark against Russia.

Many Jewish chaplains serve in the military only part-time. They fit the training into already-busy schedules leading congregations and providing pastoral care to people in their own communities.

Several military rabbis told JI that they view their mission as more than counseling the soldiers in their care and helping them deal with the hardships of military service. They explained that it’s also about reminding American Jews — many of whom have parents or grandparents who fought in World War II, Korea or Vietnam — about the value of service. During World War II, the military printed pocket-sized Hebrew bibles for Jewish soldiers. Today, some Jews don’t know anyone serving in the military.

“Most Jews in America are not connected in any way, shape or form to the United States Armed Forces. The common reaction many of us get, when we go into the armed forces here in the States is, ‘Oh, you don’t want to go into the IDF?’ or, ‘Why didn’t you go into the IDF?’ And for the record, I happen to be a very strong Zionist,” Melman told Jewish Insider in an interview last week. “One of the things for me that I’ve really grown to appreciate is trying to connect the younger generation of American Jews into joining or thinking about joining the military and how important it is.”

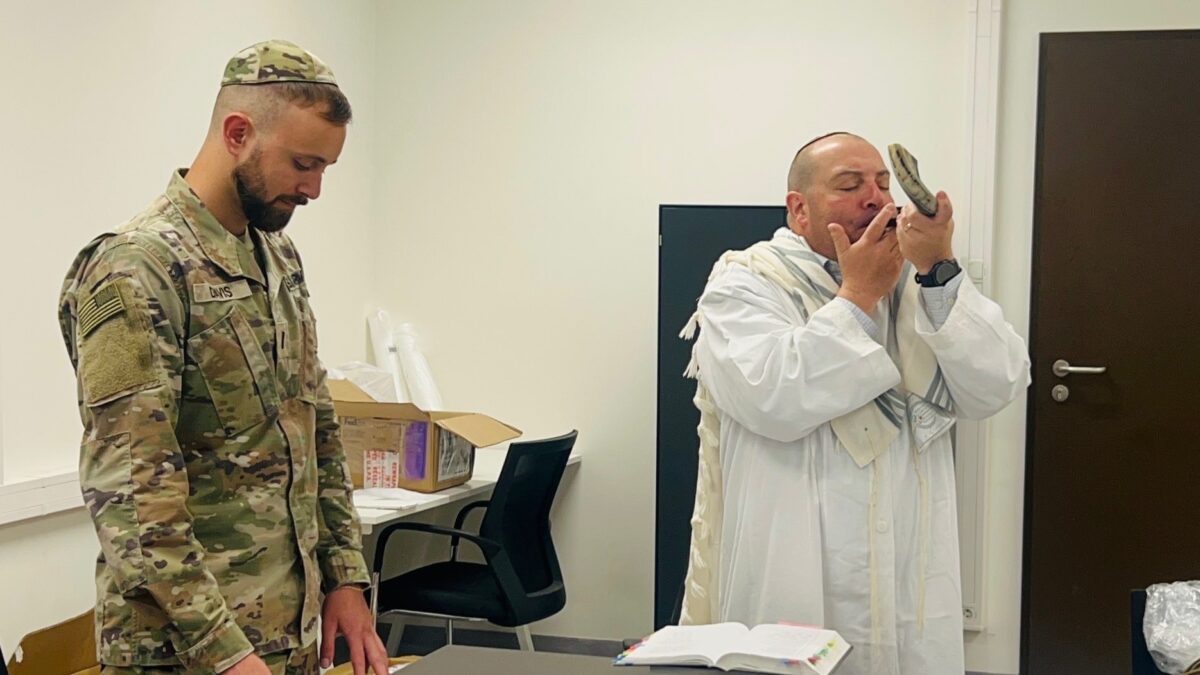

Rabbi Aaron Gaber spent nine months at Grafenwoehr, a major American base in Germany, starting last summer. As a member of the Pennsylvania Army National Guard, his unit’s mission was to train Ukrainian soldiers, and Gaber was tasked with training Ukrainian chaplains. He took them to the Memorium Nuremberg Trials, a museum located inside the German courtroom where Nazi leaders were tried for their crimes after World War II.

“That created a whole conversation about moral integrity and personal courage. How do you say to your commander, ‘Don’t commit atrocities’? Or how do you keep your soldiers who are angry at what’s happening and want to do things that are unethical or immoral from doing that?” Gaber told JI. “That elicited a whole conversation on a theological level about light versus darkness, good versus evil, but also then on a practical level: How do you advise your commander in a way that gives him or her the option not to do something that shouldn’t be done?”

Most of Gaber’s job, when dealing either with Ukrainian troops or American, involved assisting people who were not Jewish.

“As a rabbi, I got to make sure every week there was a Protestant worship service happening,” said Gaber, who returned from Germany in June (and specified that he did not lead those services).

Last year, he volunteered to spend the High Holidays in Poland and Lithuania. He drove between several different bases to make sure Jewish soldiers had access to religious services, food and learning opportunities tied to the holidays.

“I take the idea of ohr l’goyim, or bringing light to the world, I was able to bring light to the world. I was able to help Jewish soldiers celebrate their faith. If I met 10 Jewish soldiers through the entire two weeks, that was a lot. So it was individual work,” Gaber said. “In one case, I had one soldier travel, I think, three hours each way to be able to spend an hour with me. He couldn’t go by himself, so he had a noncommissioned officer, one of his squad leaders, go with him. That was the length that the military can and does go to make sure soldiers can access their faith.”

Ohr l’goyim is a phrase that comes up often for Jewish military chaplains. For Rabbi Laurence Bazer, a retired U.S. Army colonel who is now a vice president at the JCC Association and the Jewish Welfare Board’s Jewish Chaplains Council, those words — from the Book of Isaiah — commanded him to be a light unto the nations. “And that’s not just to our own fellow Jews, but to the rest of the community,” Bazer told JI.

A friend of his from the North Dakota National Guard once took Bazer, who served in the Massachusetts Army National Guard, to visit North Dakota’s state partner in Ghana. He sat down with a group of Ghanaian soldiers and told them to ask him anything they might want to know about Judaism.

“Now, these are all Catholic, Protestant and Muslim chaplains from the Ghanaian army,” Bazer recalled. “I said, ‘You could ask me, like, why Jews don’t believe in the New Testament, or Jesus, whatever.’ That’s part of the role that I love doing, of being, again, ohr l’goyim, a light unto the nations, to be able to share the positive, affirming side of Judaism so that they felt enriched. It was all in true fellowship of, we’re all servants of the Divine.”

Bazer spent his final years in the military in Washington, working full time in an active duty role at the National Guard’s headquarters. He oversaw the religious response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2020 racial-justice protests and the Jan. 6 Capitol riot.

“I was advising commanders up to four stars at a senior level about what’s going on religiously, which really meant the moral welfare of their troops,” said Bazer, who had served in New York during the 9/11 attacks and later led the chaplaincy response to the Boston Marathon bombings in 2013. “That emotional level affects readiness, and chaplains are the key to help that readiness.”

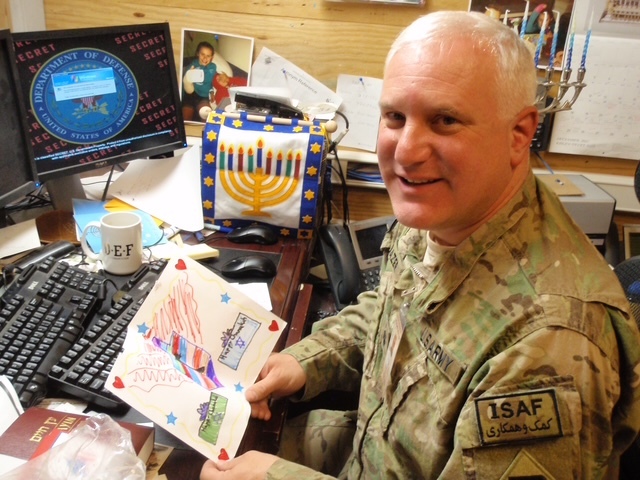

In 2023, Bazer was asked to go to Europe to lead Passover services and programming for Jewish troops. He led Passover Seders in Germany and Poland, and then drove between Lithuania and Latvia, delivering matzah and visiting with Jewish soldiers.

The Seder at Grafenwoehr took place on a large lawn on the base. After he spoke about opening the door for the prophet Elijah, a symbolic act tied to hope that the Messiah will come, a Christian chaplain on base who had attended the Seder pulled Bazer aside. He pointed to a tower that stood next to the lawn.

“He says, ‘You know, Hitler used to go up there and watch,’” Bazer said. The base — now so central to America’s operations in Europe — was once used by the Nazis. “To think that back then he used to watch the Nazis do formation, and now, in 2023 we’re holding a Passover Seder on the same base in the shadow of that tower is an incredible experience.”

Please log in if you already have a subscription, or subscribe to access the latest updates.