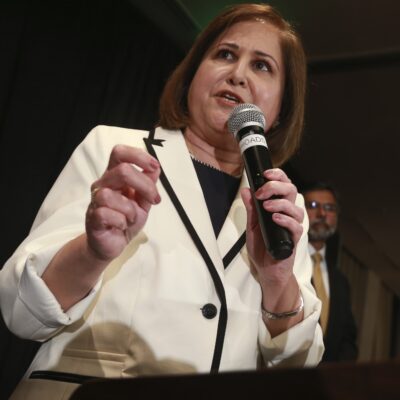

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

The Biden Education Department’s legacy on campus antisemitism

Catherine Lhamon, the assistant secretary of education for civil rights, said she worries that the slow pace of bureaucracy isn’t keeping up with the urgency of dealing with rising campus antisemitism

With just under two months left in office, Biden administration appointees are making wish lists of what they hope to achieve in the limited time they have left.

At the Department of Education, Catherine Lhamon, the assistant secretary for civil rights, knows she won’t make it through her to-do list. Not even close. There’s a crisis of antisemitism on college campuses, and Lhamon sees it — and knows she’ll have to leave office with hate raging, and several dozen unresolved investigations examining campus antisemitism.

Lhamon oversees a team of 600 attorneys who investigate schools and universities that are alleged to have violated students’ civil rights. Since the Oct. 7 Hamas terror attacks on Israel last year and the ensuing war in Gaza, the department’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) has opened a record number of investigations into discrimination based on what federal law deems “shared ancestry,” a category of discrimination that includes antisemitism and Islamophobia.

The majority of these cases, according to a review by Jewish Insider, pertain to antisemitism on American campuses. Of the “shared ancestry” investigations opened after Oct. 7, 2023, 124 are still unresolved. Just eight resolutions touching on antisemitism have been reached since Oct. 7.

“I am sick about the quantum of harm that I’m walking away from,” Lhamon told Jewish Insider in an interview last week. “Every day that any student experiences the discrimination that Congress promises that they will not, I am sick about it.”

“The Education Department really needs to take action in egregious cases that will put the federal education funds at risk,” said Ken Marcus, the founder of the Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law and OCR’s director in the Trump administration.

Some critics say too little is happening, and that the actions that are happening are taking place too slowly. (Lhamon has in part blamed the slow pace of the investigations on Republicans for opposing President Joe Biden’s requests to increase her office’s budget.)

Ken Marcus, the founder of the Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law and OCR’s director in the Trump administration, argued that investigations of universities must be coupled with a legitimate threat that they could have their federal funding stripped if they don’t comply with anti-discrimination mandates. That’s the basis of Title VI, the anti-discrimination statute that serves as the basis for the Education Department’s investigations of antisemitism: It applies to all institutions that receive federal funds. (Even private universities receive significant funds from the federal government.)

“The Education Department really needs to take action in egregious cases that will put the federal education funds at risk,” said Marcus, who has expressed openness to returning to his former post at OCR.

Congressional Republicans called in October for a “fundamental reassessment of federal support for postsecondary institutions that have failed to meet their obligations to protect Jewish students, faculty, and staff.” It’s a position echoed by President-elect Donald Trump: “Colleges will and must end the antisemitic propaganda or they will lose their accreditation and federal support,” he said in virtual remarks to the Republican Jewish Coalition’s September conference.

But Lhamon threw cold water on that possibility, with a veiled rebuttal to those like Marcus and Republicans in Congress who suggest that federal funding for American universities can simply be withdrawn in an instant.

“The statute that we enforce requires that that process is not speedy,” she said, outlining an exhaustive list of steps before a decision is made, which could ultimately end up before the Supreme Court. “That is a slow process.”

The approach taken by Lhamon and the Biden administration toward addressing campus antisemitism is an incremental one and they believe wholeheartedly in its ability to help better the lives of students who have experienced discrimination.

At its core, the issue is a human one — not a statutory one. When asked about the Biden administration’s legacy as it relates to campus antisemitism, Lhamon dispensed with the legalese to acknowledge the human cost.

“I live every day with the reality that there are people who are being hurt who choose not to come to us because they don’t know about us, because they don’t trust us, because they don’t expect that relief is forthcoming,” Lhamon said. “That’s still true even with the enormous influx of complaints on this topic.”

“I worry sometimes that the high-level examination, or the examination in a pre- or post- Oct. 7 universe, misses the experience of a student who feels hated because the student is Jewish,” Lhamon said. “That’s the thing that we’re supposed to be responding to with urgency and making sure that is not the experience of our kids at school, so that they’re actually able to learn something other than hate at school.”

She did not take a victory lap on combating antisemitism. Far too many open cases remain unresolved for that, not to mention all the instances of campus discrimination that she knows are taking place that will never be reported to the Education Department.

“I live every day with the reality that there are people who are being hurt who choose not to come to us because they don’t know about us, because they don’t trust us, because they don’t expect that relief is forthcoming,” she said. “That’s still true even with the enormous influx of complaints on this topic.”

Still, in the waning days of her tenure — her second stint in the role, which she also held in the Obama administration — Lhamon wanted to make it known that progress has been achieved in her fight against antisemitism in educational institutions, even as some within the Jewish community have called for stronger, more decisive action.

“We’ve resolved nearly three times as many cases with agreements as the last administration did in all four years, and we’ll secure more agreements in the remaining months that we have,” she said.

The Biden administration has reached 16 resolution agreements with universities alleged to have created a hostile environment on the basis of shared ancestry, most of which relate to antisemitism, compared to six in the Trump administration. “It is my hope that we see more and more compliance in school communities than we have seen in the past year.”

After Oct. 7, the Office for Civil Rights made a dramatic shift toward prioritizing campus antisemitism. In a matter of months, Lhamon opened more investigations into antisemitic harassment than the office ever had, as antisemitic incidents exploded across the country.

But she and her team also came face to face with the reality that procedural obstacles meant students would not get swift relief. Opening an investigation is just the start of a process that could take months or even years, at which point universities might reach an agreement with OCR — which would then still require years of monitoring to ensure compliance.

“What happens if they’re not being complied with?” said Shira Goodman, the Anti-Defamation League’s vice president for advocacy. “We want to make sure that if these universities don’t comply with these agreements, that there are some real penalties and that there’s some real oversight to ensure enforcement.”

At the universities that have settled their cases with OCR, similar themes have emerged in the resolution agreements. Generally, OCR found that these schools — including Brown University, the University of Michigan and City University of New York — did not adequately look into complaints from students of antisemitism or Islamophobia. The agreements require the schools to reassess the incidents, review their policies for addressing antisemitism and create better anti-discrimination training.

“OCR, under Assistant Secretary Lhamon, has really stepped into the major leagues of enforcement of Title VI,” said Mark Rotenberg, senior vice president for university initiatives and general counsel at Hillel International.

“On the one hand, I can look at these resolution agreements and say that they should have been much stronger,” said Marcus. “On the other hand, OCR is nevertheless having an impact. The word is getting out to colleges and universities that they should be careful to avoid one of these OCR Title VI investigations, and that they should be concerned about the prospect of a resolution agreement.”

It’s too soon to say what kind of lasting impact the Biden administration will have when it comes to protecting Jewish students. Their work has been bureaucratic and legalistic, geared at bringing university legal offices into compliance — so whether university administrators comply with Lhamon’s warnings about taking antisemitism seriously will become more clear with time.

“OCR, under Assistant Secretary Lhamon, has really stepped into the major leagues of enforcement of Title VI,” said Mark Rotenberg, senior vice president for university initiatives and general counsel at Hillel International. He attributed that to the Biden administration’s interest in antisemitism, as well as the record-breaking amount of hate facing Jewish students.

Plus, Rotenberg added, the Jewish community has begun to turn to the legal process more frequently than ever before, bringing complaints with OCR in record numbers. Hillel International, the ADL and the Brandeis Center even set up a legal helpline for Jewish students, which received more than 650 requests for assistance from students in the first nine months after it was created last November.

OCR, Title VI and federal civil rights legislation are still complicated legal matters; while they are now better known topics in the Jewish community, conversations about legal compliance can still feel miles away from the actual issue, which is that Jewish students feel ostracized, unsafe or uncomfortable on their campuses. It doesn’t take Washington jargon to explain that Oct. 7 and the Gaza war created a permission structure for hostility toward Jewish students in educational institutions nationwide.

“I don’t look back at the past 13 months. I look back at these four years,” said Lhamon. “We saw antisemitic hate in schools, and we addressed it before Oct. 7.”

Still, antisemitism remains a fact of life at many campuses. While Lhamon has been working within the system to make sure university leaders know their legal obligations (she said she is “aghast” by how many lack knowledge about these issues), and that they follow federal law, Jewish students still face discrimination and exclusion.

She knows that — and she knows that she can’t fix all of it.