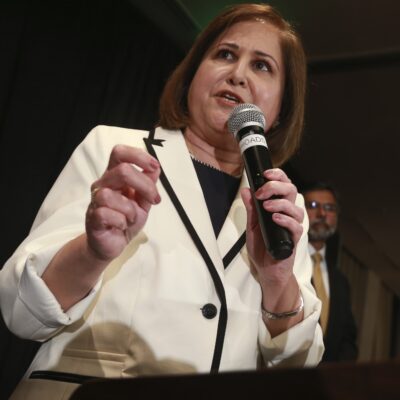

Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images

‘The call is coming from inside the house’: Why queer Jews fear discrimination at Pride events this year

Rep. Ritchie Torres (D-NY): ‘There are anti-Israel LGBTQ activists who are essentially telling Jews to be in the closet about their Judaism and Zionism … That's a perversion of pride.’

Five years ago, the DC Dyke March — an annual protest march and rally held by and for the lesbian community, usually the day before the larger Capital Pride celebration — faced accusations of antisemitism for banning Israeli flags and rainbow Jewish pride flags with a Jewish star in the middle. Palestinian flags were allowed to fly.

Nate Shalev, a Jewish inclusivity speaker and adviser, was an organizer of the New York City Dyke March at the time. Shalev, who uses they/them pronouns, worked with fellow New York organizers to ensure that a similar ban didn’t make its way there. They argued for acceptance of people of all national identities: “We want the Dyke March to be as inclusive as possible for as many dykes as possible,” Shalev told Jewish Insider this week.

But this year, that principle has been discarded. The theme of the Dyke Marches in Washington and New York is “Dykes Against Genocide,” a response to the war in Gaza. Shalev will not be attending that march, or any marches.

“Any large, queer gathering, queer liberation march, I know I’m not going to go to because it doesn’t feel safe to me,” Shalev said. “I know that there’s just a large amount of antisemitism, this conflagration of antisemitism and anti-Zionism about where the line is. I know folks feel very strongly that they know where the line is, but they often don’t, based on the signs that we’ve been seeing and the violence that happens.”

As millions of LGBTQ people and their allies make plans to take part in Pride parades around the country this month, many Jewish members of the queer community are skeptical about joining the celebrations, fearful that their Jewish identity will lead them to face exclusion from a community that has for decades argued forcefully about the power of inclusion.

“I’ve been telling folks that you do what makes you feel comfortable, but know that the Jewish community is behind you, and we have each other’s backs,” said Josh Maxey, executive director of Bet Mishpachah, an LGBTQ synagogue in Washington, D.C. “This is not a moment in time where we should feel, as a Jewish community, we need to go into hiding.”

“Pride is about us coming together as members of the LGBTQ community, whether you are Jewish or not, of all faiths, and really celebrating who we are,” said Josh Maxey, executive director of Bet Mishpachah, an LGBTQ synagogue in Washington, D.C. “Being Jewish is a part of who we are, and just like we wouldn’t expect any other group to turn off parts of their identity during Pride, we shouldn’t be doing that for our Jewish folks who are participating in these Pride celebrations.”

In recent weeks, Maxey has been fielding calls from queer Jews who are afraid to participate in this weekend’s Capital Pride celebration, asking if they should take off their yarmulkes or their Stars of David, or if they should skip the festivities altogether. The concerns were significant enough that Bet Mishpachah and several other Jewish organizations wrote an open letter to the Pride community, urging Pride participants to be inclusive and welcoming of Jewish attendees.

“Trans people are less likely to attend Pride events because they don’t always feel safe. But in that case, the harm is generally coming from outside the LGBTQ community,” said Ethan Felson, executive director of A Wider Bridge, a nonprofit that builds ties between LGBTQ communities in North America and Israel. “Here the call is coming from inside the house.”

“I’ve been telling folks that you do what makes you feel comfortable, but know that the Jewish community is behind you, and we have each other’s backs,” Maxey said. “This is not a moment in time where we should feel, as a Jewish community, we need to go into hiding.” Organizers of Capital Pride, he added, have been very supportive of the Jewish community’s participation.

The litmus tests faced by queer Jews in some circles after Oct. 7 — to condemn Zionism and agree with allegations that Israel is committing a genocide — mirror those facing Jews in other progressive communities. But many in the LGBTQ community say there is an added level of pain in a community that purports to hold as a key value the acceptance of each person as they are. It’s a community that is used to threats and intimidation; usually, though, the threats come from homophobic actors outside their circles.

“Trans people are less likely to attend Pride events because they don’t always feel safe. But in that case, the harm is generally coming from outside the LGBTQ community,” said Ethan Felson, executive director of A Wider Bridge, a nonprofit that builds ties between LGBTQ communities in North America and Israel. “Here the call is coming from inside the house.”

At Pride parades that have already taken place, violent anti-Israel messaging has been present. In a Pride parade in the gay enclave of West Hollywood, Calif., someone held a sign reading “Globalize the Intifada.” In nearby Long Beach, a group marched under a banner that read “No Pride in Genocide” alongside Palestinian flags. At last weekend’s parades in Philadelphia and Winnipeg, anti-Israel protesters blocked the parade routes to protest the war. “Long live the Intifada,” said one sign held by the Philadelphia protesters.

“Blocking Pride parades is homophobic, period. It’s transphobic. You don’t do that,” said Tyler Gregory, CEO of the Bay Area Jewish Community Relations Council who was the executive director of A Wider Bridge from 2018-2020.

The JCRC and the San Francisco JCC organized a large float for a Jewish bloc to march in this year’s San Francisco Pride Parade on June 30. The Jewish community has participated in the parade for years, but it’s the first time they’re “going all out with a float and dancers,” according to Gregory. “We think that marching loudly in Pride as Jews is more important this year than ever,” he added. They registered their float several months ago in anticipation of anti-Israel displays that will also appear in the parade.

The San Francisco Pride Parade, one of the largest in the country, announced on Tuesday that there would not be an Israeli float at the parade, but that pro-Palestinian groups were welcome and could join the “Resistance Contingent” — and pro-Palestinian organizations that wanted to have their own contingents could request to have the fee waived to participate in the parade.

“SF Pride values the contributions of Jewish queer individuals in advocating for peace and acknowledge their enduring efforts,” the statement reads. “SF Pride is careful not to conflate Jewish groups and Jewish people living in America with the state of Israel.”

After facing pressure from Jewish activists, the organization released a statement on Thursday clarifying that “absolutely all LGBTQ+ people and allies are welcome at San Francisco Pride, and that includes Israelis and Jewish people just as it does Palestinians and Muslims.”

In New York City, home to a major Pride parade, the Israeli Consulate has marched with a float for well over a decade. When asked whether they will do so again this year, a spokesperson for the consulate did not respond to a request for comment. A source involved with planning the parade said that in recent years, it has become harder for Israel to participate, citing anti-Israel sentiment directed at the marchers.

Two years ago, in a show of Jewish and gay pride, the Israeli float in the Manhattan parade featured an iconic image of David Ben-Gurion doing a handstand on the beach, superimposed on top of a rainbow surfboard on the float. Israeli pop star Noa Kirel performed atop the float. The following year, she represented Israel in the Eurovision Song Contest — another event that has recently sparked a wave of hostility toward Israel, including from within the LGBTQ community.

A gay bar in Brooklyn, 3 Dollar Bill, canceled a planned screening of this year’s Eurovision finals in May after facing widespread boycott calls from people who objected to Israel’s participation in the contest. (Israel has appeared in the contest for more than 50 years.) The bar caved to the pressure and canceled the event. But then, after facing a backlash by its Jewish clientele, 3 Dollar Bill backtracked and agreed to host the party.

A strong anti-Zionist bent existed in corners of the LGBTQ community prior to the Oct. 7 Hamas attacks in Israel, but it has exploded in the months since. Sharply anti-Israel activists organizing under the “Queers for Palestine” banner have been among the most vocal advocates for a cease-fire dating back to soon after the war began last fall. Organizations and activist groups that had never or only occasionally weighed in on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have now made opposition to the war, and to Israel, a key part of their identity.

“There is this litmus test that, OK, to be a part of the LGBTQ community, then you have to hold all of these viewpoints, and not have anything differing from the rest of the group,’ and that, I think, is just not fair, and I think it does nothing but divide us,” said Bet Mishpachah’s Maxey.

“On the American left, homophobia and racism are socially unacceptable unless the target is a Zionist, like myself. Or the anti-Zionists have made an exception to the rule against homophobia and racism,” Rep. Ritchie Torres (D-NY) told JI. “I find it truly ironic that there are anti-Israel LGBTQ activists who are essentially telling Jews to be in the closet about their Judaism and Zionism, to be ashamed of their Judaism, and that to me is not pride. That’s a perversion of pride. That’s the antithesis of what the LGBTQ community should stand for.”

Shalev, the former Dyke March organizer, described it as “an exclusionary inclusion.”

“It’s the way that queer communities can keep one another safe, and so it’s saying, ‘In this circle, we won’t allow any transphobia, or we won’t allow any racism, because we want to keep one another safe,’” said Shalev. Now, many queer spaces have placed Zionism outside that circle (erroneously, as Shalev sees it).

At the start of Pride month in June, ACT UP NY, an iconic anti-AIDS group, tore down a poster of Rep. Ritchie Torres (D-NY) that was hanging in Trailblazers Park, a public space in Fire Island that opened two years ago to honor LGBTQ heroes. The group called Torres, a vocal supporter of Israel and one of the first two openly gay Black men to serve in Congress, “anything but a trailblazer.”

“On the American left, homophobia and racism are socially unacceptable unless the target is a Zionist, like myself. Or the anti-Zionists have made an exception to the rule against homophobia and racism,” Torres told JI on Thursday. “I find it truly ironic that there are anti-Israel LGBTQ activists who are essentially telling Jews to be in the closet about their Judaism and Zionism, to be ashamed of their Judaism, and that to me is not pride. That’s a perversion of pride. That’s the antithesis of what the LGBTQ community should stand for.”

Gregory, the JCRC director in San Francisco, called the anti-Israel segment of the LGBTQ community a “minority,” like in other communities. “You have to remember that like in any other group, the extremes are being amplified,” he said.

Still, Jewish LGBTQ advocates argue that requiring queer Jews to check a crucial part of their identity at the door can have real consequences. Even when it isn’t an overt requirement, the seed of exclusion has been planted.

“What I worry about is a 17-year-old trans Jewish kid who has to make a decision: Do I put some part of my identity into a closet in order to be emotionally and physically safe?” asked Felson, of A Wider Bridge. “I would hope that the people who are using intimidation, harassment and sometimes violence as a tactic might pause to think about that young person, and what Pride meant to them the first time they came as their full, authentic self.”