Courtesy

Welcome to Washington’s new ‘school’ of contemporary art

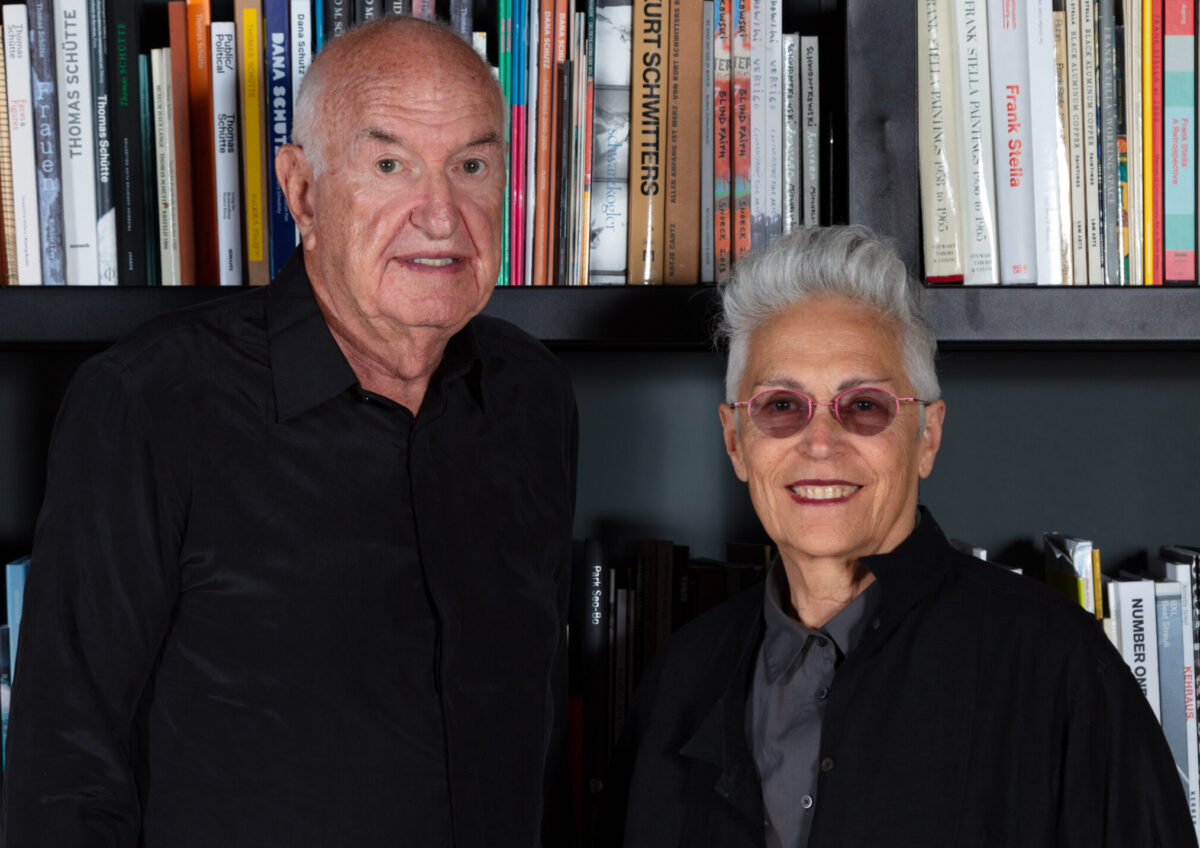

Powerhouse art collectors Mera and Don Rubell, who revolutionized the art scene in Miami, have opened their second art museum, in Southwest Washington

Growing up in the shadow of the Holocaust, Mera Rubell learned one lesson from her childhood in a Displaced Persons camp in Eastern Europe: “If you want to survive, don’t get attached to objects.”

So it’s ironic that Rubell, now 80 years old, has come to be known for the objects she collects. To be precise: more than 7,000 works of art, objects she cherishes and displays in museums built by her and her husband, Don Rubell.

Their latest museum opened in Washington, D.C., last fall, a calming art oasis in a neighborhood better known for its proximity to political deal-making and shoulder-rubbing. In a city chock full of museums, the Rubell Museum DC brought a contemporary and fast-paced flavor to sit alongside the history and authority of the venerable institutions of the Smithsonian.

“At some point right before opening, we said, ‘Wow, coming into a city with all the greatest museums on earth is extremely intimidating,’” said Mera Rubell, who comprises one-half of a famed art-collecting couple with a unique gift for identifying and nurturing young talent.

The museum, located less than a mile south of the U.S. Capitol, includes works solely from the private collection of Mera, 80, and Don, 83. Their collection contains artwork that the couple first started acquiring more than half a century ago, when Mera was a teacher and Don was in medical school.

But before even their modest start as twentysomethings, both Don and Mera came from backgrounds that were very far from the art world they would later enter.

Don grew up in New York City, the son of a Latin teacher and a postal worker. Mera was born in Tashkent, then part of the Soviet Union, to Polish Jews fleeing the Holocaust. Her family moved to Israel before coming to America. (She and Don will be going to Israel this year to celebrate their 60th wedding anniversary — her first visit since they played tennis in the Maccabiah Games more than 30 years ago.)

Her earliest memory, she told Jewish Insider, is a scene that played out multiple times in her childhood: hiding under the kitchen table in a crowded home at an American Displaced Persons’ camp in Europe, when people stopped by to ask if anyone had seen their missing family member. Usually, the answer was no.

“For some kids, fairy tales can be very impressionable,” Rubell said. “You can only imagine hiding under the table and hearing the brutality and the loss and the pain that these people were sharing with each other over tea [in the] communal kitchen.”

Don and Mera met and married when they were both in their twenties, with career paths that had nothing to do with art.

“We lived in a five-story walk-up [in New York City],” Rubell told JI last month. “We actually made a decision that to paint the apartment was going to be more expensive than to simply cover the holes.” Within years, there was more art covering the walls than visible wall space.

That the Rubells are now two of the best-known contemporary art collectors in the world is still something of a surprise to them both.

“It was many, many years before the concept of collector fell into our head, because you have to understand that when we first bought the first piece we bought, I was earning $100 a week — I had a $5,300-a-year teacher’s salary — and we bought the first piece for $25,” she recalled.

In the decades that followed, they supported some of the biggest names in contemporary art, including Keith Haring, Cindy Sherman, Jeff Koons and Jean-Michel Basquiat. With an inheritance from Don’s brother in 1989, the Rubells entered the commercial real estate business and began to collect even more aggressively.

“The basic truth is that you never have enough money to collect art,” Rubell said. “All the artists that we have in our collection now, we could never buy them today. No way, no how.”

“We never saw ourselves,” she continued, “as ‘big collectors.’ What gave us a leg up always was our ability to connect with young gallerists and young artists.” She quickly and excitedly launched into a discussion of the work of Doron Langberg, a young Israeli artist to whom she is currently drawn — just one result of her nonstop hunt for the best new art.

The Rubells opened their first museum in a converted DEA facility in Miami’s Wynwood neighborhood in 1993, setting off a process that utterly transformed Wynwood into one of Miami’s most popular areas and a hub of modern art. They attracted the famed Swiss art festival Art Basel to Miami Beach, its first and only outpost in the United States.

So what convinced two avant-garde art luminaries to bring their contemporary art collection to Washington, with its reputation as a buttoned-up, status-conscious city?

In large part, it was a real estate decision. The Rubells owned a hotel across the street, and they watched the building that now houses the art museum deteriorate. It had housed the Randall School, a segregated junior high school; after it closed, the building fell apart, eventually becoming totally dilapidated. It took almost two decades from when the Rubells first conceived of the museum until they finally figured out how to acquire the building, renovate it and, eventually, create the museum. Admission is free to D.C. residents and otherwise costs $15.

The original schoolhouse structure still stands. The main room of the 32,000-square-foot gallery is an airy, bright space, with large arched windows and brick walls and only four pieces of art — two large paintings and two massive textile works, by artists including the American painter Kehinde Wiley (who painted the flower-filled portrait of former President Barack Obama that hangs in the National Portrait Gallery) and the Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui.

These works are the centerpieces of a Marvin Gaye-inspired exhibition titled “What’s Going On.” (Gaye, who wrote the anthemic 1971 song of the same name, attended the Randall School.) It is a space meant to be savored in stillness. Still, it invites conversation: Why these works? What do they have to say alone, and alongside each other?

“There’s a lot of engagement because it’s a very, very articulate, educated population,” Rubell noted. “Washington is a highly informed population. The people that come in are just so impressive. They read, and they’re politically involved.”

A slow walk through the rest of the exhibits, set over three floors and a basement, reveals the bones of the old schoolhouse, with doors removed to create a seamless experience for visitors. Each old classroom is now devoted to a single artist. The artworks make use of a range of mediums — painting, textile, audio, found objects, ceramics. All of it is contemporary, that elusive term that can mean a million different things to each person.

“Whether you’re a collector, or someone who goes to a museum, if you bring your consciousness to an artwork, it’s amazing what you can get out of it,” said Rubell. “If you’re looking at contemporary art, as I said, it’s like looking, like talking to a person your age, and dealing with the issues that you’re confronted with either in your life or around you or people you know. It’s so relevant.”