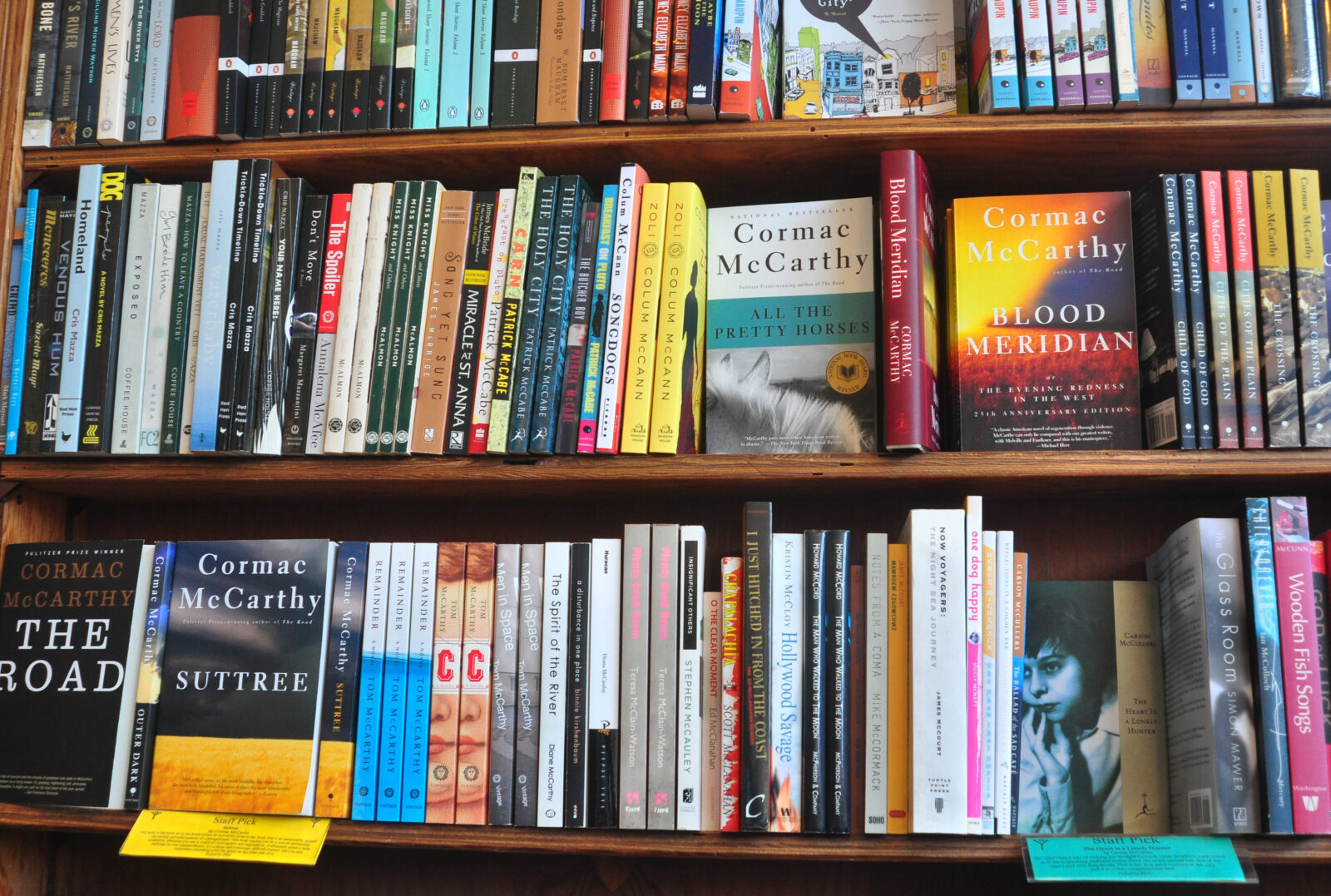

Photo by Robert Alexander/Getty Images

Cormac McCarthy’s long-held admiration for Jewish achievement culminated in his final two novels

The author’s decision to make the Western siblings in ‘Stella Maris’ Jewish has continued to puzzle McCarthy scholars

When Cormac McCarthy published his final two novels in quick succession late last year, it did not go unnoticed that he had created his first major female protagonist: Alicia Western, the tortured mathematical genius at the center of Stella Maris — a hauntingly rendered transcription of her therapy sessions at a psychiatric institution in rural Wisconsin.

In form and focus, the book was an unusual departure for McCarthy, a titan of American literature who died two weeks ago, just short of his 90th birthday. His best-known protagonists had long been recognized as almost mythic avatars of a certain kind of masculine stoicism embodied by Alicia’s brother, Bobby, a laconic salvage diver whose story is told in a companion novel, The Passenger, which is more conventionally structured.

Equally intriguing, however, was that McCarthy had made the siblings Jewish. It was a curious biographical choice that has continued to puzzle McCarthy scholars who have scoured the books for insights into his decision. The most reasonable explanation, it seems, is that McCarthy was motivated, at least in part, by a commitment to historical reconstruction: The siblings’ father, a brilliant physicist who studied with Einstein, worked on the Manhattan Project, where a number of Jewish scientists helped design the atom bomb.

The Westerns are tormented by their connection to the project and the destruction it ultimately wrought. Bobby, for instance, “fully understood that he owed his existence to Adolf Hitler,” McCarthy writes in a characteristically portentous passage. “That the forces of history which had ushered his troubled life into the tapestry were those of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, the sister events that sealed forever the fate of the West.”

Aside from such musings, though, the topic of Jewish identity is hardly explored in the novels, where McCarthy more notably demonstrates his conceptual understanding of physics in a series of abstruse disquisitions. “I tried very hard to find Yiddishkeit somewhere in there,” Rick Wallach, the founder of the Cormac McCarthy Society, said in an interview with Jewish Insider not long after the novels had been published. “I don’t see it.”

But the Westerns’ Jewish heritage was likely more meaningful to McCarthy than his own renderings might suggest. In some ways, it could be interpreted as a testament to a privately held — and little-known — reverence for the Jewish experience. The author had “a sincere pattern of admiration for Jewish people and Jewish culture,” said Bryan Giemza, an associate professor of humanities and literature at Texas Texas Tech University and the author of Science and Literature in Cormac McCarthy’s Expanding Worlds, published earlier this month.

Giemza’s knowledge of McCarthy’s personal sentiments, he said, is based on conversations with people close to the author, who was famously guarded. “He holds Jewish people in great esteem,” Giemza confirmed to JI before McCarthy’s death.

That esteem was cemented in large part by McCarthy’s affiliation with the Santa Fe Institute, a nonprofit theoretical research center founded in 1984. McCarthy, who was raised in an Irish Catholic family in Tennessee, had no ancestral connection to Judaism. But he spent the last decades of his life surrounded by some of the world’s most accomplished Jewish physicists who were involved with the institute, where he was a longtime trustee.

It was there that he wrote his post-apocalyptic novel The Road, which won a Pulitzer Prize. His engagement, however, wasn’t limited exclusively to literary production. McCarthy could also hold his own in regular conversations about math and science over tea with the institute’s members, including its late co-founder Murray Gell-Mann, the Nobel Prize-winning particle physicist who became a close friend. Nearly all of the institute’s eight founders, meanwhile, had worked on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos in New Mexico — where the fictional Westerns’ father also served.

Geoffrey West, a British-born physicist and a researcher at the institute, said he wasn’t surprised when he learned that McCarthy had written a pair of Jewish characters who are prodigious at mathematics. “Most of the people he admired as scientists were Jews, and it’s very natural to make one of these people or two of these people Jewish,” he reasoned. The decidedly un-Jewish surname “is strange,” he acknowledged, even if it bears a resemblance to his own. “But nevertheless.”

West, a former president of the Santa Fe Institute who grew up in an Orthodox Jewish household, said he never asked McCarthy why he had given his characters Jewish backgrounds. They only talked “a teeny bit” about the books and “not in any great detail,” he said. McCarthy, who rarely engaged with the press, never publicly addressed the matter. His publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, declined multiple interview requests from JI before his death.

In lieu of a deeper answer, then, readers are left with the books themselves, which offer only a limited number of clues. In one particularly notable passage from Stella Maris, however, Alicia provides a key insight into her own relationship to Judaism when she is asked by her Jewish psychiatrist, Dr. Robert Cohen, if she “has any Jewish family connections.” No, she says, adding that she and her brother “didn’t grow up Jewish.”

“But you knew you were Jewish,” Dr. Cohen responds flatly.

“No. I knew something,” Alicia, who has checked herself into the psychiatric ward after experiencing hallucinations, says somewhat puzzlingly, before arriving at her central observation. “Anyway, my forebears counting coppers out of a clackdish are what have brought me to this station in life,” she continues. “Jews represent two percent of the population and eighty percent of the mathematicians. If those numbers were even a little more skewed we’d be talking about a separate species.”

If Alicia is aware that her assessment is “farfetched,” as Dr. Cohen diplomatically suggests, she does not seem to care. It isn’t “fetched far enough,” she claims, even while recognizing that there are limitations to explaining her theory. “Darwin’s question remains unanswered. How do we come by mental abilities that have no history?” she wonders, adding, “How does making change in the market prepare one’s grandchildren for quantum mechanics? For topology?”

McCarthy had long been fascinated by coins and currency, a recurring symbol across his novels, but Alicia’s belief in a kind of heritable Ashkenazi intelligence seems largely unrelated to that fixation. “If I’m not mistaken, that’s lifted straight from The Bell Curve, which of course has been pilloried, for good reason,” Giemza, the McCarthy expert, told JI, referring to a long-discredited book that posits a direct connection between race and intelligence. “It’s never good when you get into genetic essentialism.”

In an interview, Giemza confessed that he was “a little surprised” and somewhat “disappointed” to find the passage, even as he acknowledged that Alicia is floating a theory that “a lot of people” would probably be inclined to believe. “If you look at people of McCarthy’s generation, kind of Anglo-Americans, there is the notion among some that God’s chosen people applies to intellect and ability,” he told JI.

Still, he made sure to clarify that he was not attributing such thinking to McCarthy himself, anticipating that some critics “might be tempted to generalize about Jewishness as the common theme” to explain McCarthy’s friendships with scientists — an idea he views as misguided. But he questioned McCarthy’s reason for including the passage at all. “It’s kind of like, well, to what end?” he wondered. “What does it serve?”

It was not the first instance in which McCarthy had suggested a link between Jewish heritage and mental acuity. In his 1992 novel All the Pretty Horses, the first installment in his popular Border Trilogy, one character recounts, in prophetic detail, the colonial history that led her ancestors to Mexico. “There had always been a rumor that they were of jewish extraction,” McCarthy writes, lowercase his. “Possibly it’s true. They were all very intelligent. Certainly theirs seemed to me at least to be a jewish destiny. A latterday diaspora. Martyrdom. Persecution. Exile.”

McCarthy’s decision to lowercase “jew” was in keeping with his idiosyncratic aversion to standard grammatical conventions — he also eschewed quotation marks, for example. He had opted for the same usage in Blood Meridian, an anti-western that is widely viewed as his finest novel, while referring to a “Prussian jew named Speyer,” who is among just a handful minor Jewish characters McCarthy would write into his novels until he gave them central roles in his last two works — where all Jewish references are capitalized.

While it is unclear when exactly McCarthy decided that he would make the Westerns Jewish, early drafts of The Passenger, which he began writing decades ago, indicate that it was not his original plan. Lydia Cooper, a professor of American literature at Creighton University in Omaha, has reviewed McCarthy’s drafts written roughly between 2000 and 2004, which were recently made publicly available in an archive held at Texas State University.

“I didn’t see anything in those drafts that gave any indication the Western siblings are Jewish, and several minor indications they’re not,” she told JI, noting that there are references to Bobby being educated by nuns. In another draft, according to Cooper, “we are told that Bobby Western’s father had married before and not told their mother that he’d been married previously because his first wife ‘was Catholic.’” That line mostly echoes the published text, with one notable exception: Their father’s first wife became an “Orthodox Jew.”

No obvious reason is given to explain why the Westerns’ father would hesitate to reveal to his second wife that he had been married to an Orthodox Jewish woman. But Cooper suggested that might be beside the point. “McCarthy didn’t just shift the main characters to being Jewish,” she said, “but he was intentional about it, to a certain extent.”

From a biological standpoint, “it doesn’t matter” that the siblings’ father’s first wife was Jewish rather than Catholic, “but it creates a bit more context for the father’s backstory,” Cooper elaborated. “If I had to describe it, it feels to me like McCarthy decided his protagonists needed to be Jewish, and he transposed their identities, like a musician shifting the same melody to a different key.”

Notably, she said, “most of the lengthy sections on physics from both novels aren’t in” the papers she reviewed. The absence of such material, she observed, suggests that McCarthy had likely begun to depict his characters as Jewish “around the time that he really started delving into the physics.”

Meanwhile, Giemza said he had learned that Alicia is modeled, in part, on a woman who had been a “visitor” at the Santa Fe Institute but is not, to his awareness, “of Jewish ancestry.” The Jewish element, he speculated in an email to JI, “seems to be a kind of artistic imposition, to what end, we will long be musing.”

In a new paper recently presented at an online salon hosted by the Southwest Popular/American Culture Association, Wallach, the Cormac McCarthy Society founder, seeks to examine how the “Westerns’ Judaism” functions in a manner that is “more significant than a historical referent to” what he calls “the Los Alamos ethnic mix.”

“As we can see, the most apparent signification is its resonances with the age-old theme of persecution and exile,” he writes of Bobby in particular, who is pursued by threateningly anonymous agents after he finds that a body is missing from a sunken jet during a salvage dive off the coast of New Orleans. “Stripped of his worldly goods and threatened with likely imprisonment, Bobby is forced to flee, a ‘wandering Jew’ set on an aimless retreat through heartland America and ultimately driven abroad to a sanctuary in Spain.”

Bobby’s persecution “by this nameless, faceless government,” Wallach said in an interview with JI, is reminiscent of what he characterized as a kind of Kafkaesque nightmare.

But like most of McCarthy’s books, it is far easier to discern Catholic influences rather than Jewish themes. Perhaps most notably, The Passenger opens with Alicia’s suicide, her lifeless body found hanging “among the bare gray poles of the winter trees” on a “cold and barely spoken Christmas day.” It concludes during Holy Week in Ibiza, where McCarthy finished his second novel, Outer Dark, in the 1960s.

That book, set in the Appalachian South around the turn of the 20th century, features what is likely the first overt Jewish reference in McCarthy’s oeuvre. It’s a humorous exchange in which one character asks guilelessly, “What’s a jew?” The answer, delivered by an amiable hog herder, is that a Jew is “one of them old-timey people from in the bible.”

Among the most meaningful demonstrations of McCarthy’s understanding of Judaism comes from an unexpected source: His screenplay for The Counselor, a 2013 crime thriller directed by Ridley Scott. In one scene, an unnamed Jewish diamond dealer unspools an oracular description of what he regards as the unique fate of the Jewish people. “There is no culture save the Semitic culture. There,” the dealer begins. “The last known culture before that was the Greek and there will be no culture after. Nothing.”

Speaking to the titular counselor, he goes on to argue that the “heart of any culture is to be found in the nature of the hero,” adding: “Who is that man who is revered? In the western world it is the man of God. From Moses to Christ. The prophet. The penitent. Such a figure is unknown to the Greeks. Unheard of. Unimaginable. Because you can only have a man of God, not a man of gods. And this God is the God of the Jewish people. There is no other god. We see the figure of him — what is the word? Purloined. Purloined in the West.”

“How do you steal a God? He is immovable,” the dealer concludes. “The Jew beholds his tormentor dressed in the vestments of his own ancient culture. Everything bears a strange familiarity. But the fit is always poor and the hands are always bloody.”

To Giemza, McCarthy’s assessment, told through the dealer, is “pretty darn interesting,” he said. “Here, he shows an awareness of all the trauma of Jewish history and displacement,” he told JI. “But more, he seems to suggest that, for example, American sort of WASPy culture — whatever the American mold is for any kind of Anglo-American Protestant identity — is itself a type of theft. That Christianity is little more than a secondhand elaboration on Judaism.”

“I’m not going to ascribe this to McCarthy, but I suspect that this is him,” Giemza said. “I think we get an insight into perhaps his understanding of Jewish identity and history.”

McCarthy’s reverence for abstract mathematical concepts was, perhaps, intertwined with that understanding — not least with respect to Alicia. “Some of my colleagues have asked this question: Do you think the almost mystical way she talks about mathematics has any kind of relation to her thoughts about Jewishness or just religion in general?” Stacey Peebles, an associate professor of English at Centre College in Kentucky and the president of the Cormac McCarthy Society, said in an interview with JI. “There’s probably something to be said for that, because the way she talks about math is almost like a divine presence.”

“What does it mean to think about something that is so separate from the world we actually inhabit and that you can’t visualize?” Peebles mused. “I mean, it starts to sound like God at a certain level — or, at the very least, some kind of expression of faith.”

Relatedly, West, a theoretical physicist who thinks in grand abstractions, said he has long pondered why so many Jewish scientists have been drawn, in a manner of speaking, to a discipline that involves no less a task than decoding the universe. “That, I have speculated, is because of the stubborn Jewish determinism that there’s one God,” he told JI. “That’s it. One God, which has permeated Jewish thinking from biblical times.”

“Somehow, that got morphed or evolved into the search for ‘everything is unified,’ and so it’s not surprising that Jews would end up being at the forefront of trying to understand grand unified theories of the elementary particles and the origins of the universe,” he explained. “Even though most of us are secular, deep down in our archetypal subconscious, there remains this ‘one God’ kind of concept.”

There is little reason to doubt that McCarthy, a stubborn outsider himself who felt most at home in the company of scientists, would find something to admire in that theory.