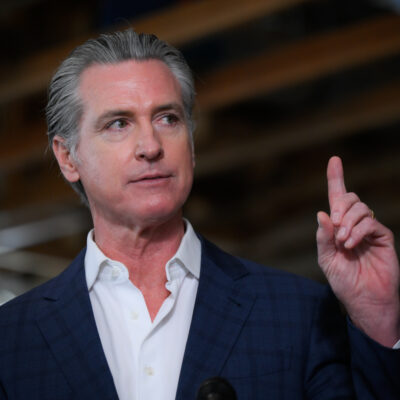

Courtesy

Meet the creator of the tool that aims to predict — and prevent — suicide

Dr. Kelly Posner Gerstenhaber’s Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale has been adopted around the world, from Israel to Iran

To recite some of the holiest prayers in Judaism, 10 worshippers must be present in a minyan. It’s one of the most stringent ways that joining together in a community is part of Judaism; in this case, it is a requirement. But the spirit of community — kehillah — is also an ingrained aspect of other parts of Jewish tradition.

It’s apparent in the way friends pool resources to deliver meals to a mourner in the days after the loss of a loved one, or the gathering of community members at a bris after a baby boy is born.

“When a community comes together, there’s hope,” said Dr. Kelly Posner Gerstenhaber, founder and director of the Columbia Lighthouse Project and an expert in suicide prevention. “Members who are different from one another [are] orchestrated for a collective undertaking for a common good when this kehillah is driven by a constructive purpose.”

That common good, Posner, 54, told Jewish Insider, can be preventing suicide, a goal that she argues is a collective responsibility.

“Just ask. You can save a life,” she explained, summing up her philosophy. “It’s a simple message that declares that asking about suicide is not difficult, and everyone is empowered to make a difference, and everyone in the community has a role in preventing suicide.”

But for Posner (who uses her maiden name professionally), “just ask” is more than a philosophy. It’s the basis of a protocol she created to detect suicidal thoughts and ideation that is backed by years of rigorous scientific research and is used in dozens of countries around the world. Known as the Columbia Protocol, the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale features a standardized set of straightforward questions to identify people who are considering suicide and to determine who is at risk of acting on suicidal thoughts.

Posner called it “a simple set of questions that can be put in anybody’s hands to identify who’s at risk.” She encourages doctors to ask these questions of their patients, but she also seeks societal change — getting the questions in the hands of everyone from teachers to librarians to parents to clergy members, so that any person feels empowered to ask a loved one about suicide. (A more detailed form is available for clinical professionals.)

“It sets up a sense of shared language and shared understanding of how to conceptualize it and talk about it,” said Nick Magle-Haberek, clinical director at BaMidbar Wilderness Therapy at Ramah in the Rockies, which uses the protocol.

Suicide kills 700,000 people around the world each year, and 47,500 Americans died by suicide in 2019 — with many more, 1.4 million, having attempted suicide that year. It is the tenth leading cause of death across all age groups and the second leading cause of death among people aged 10-34. Americans have reported increased rates of depression and anxiety since the COVID-19 pandemic began, although it is not clear whether suicide rates have risen as well.

A scientific paper published in June found that the Columbia Protocol “robustly” predicted death by suicide, although the research — conducted by a team of Swedish scientists — did not relate to COVID-19.

“A lot of the other programs, there’s just a sense of, if you hear any chatter about [suicide], or if you have a gut feeling about it, then it’s time to put somebody on what we would call a ‘suicide watch,’” said Magle-Haberek, whose organization works with Jewish young adults. “From my perspective, that’s unfair to the staff who don’t have that training. And so as a risk-management tool, I think it’s pretty exceptional.”

Posner’s work has been endorsed by major government agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute of Mental Health and the Department of Homeland Security. In 2018 she received the Department of Defense’s medal for exceptional public service at a suicide prevention event cohosted by the Department of Veteran Affairs. The six questions in the Columbia Protocol have been translated into 114 languages, according to the federal Health Resources and Services Administration.

Half the work is about preventing suicide, Posner explained, but “half of it is also about combating the stigma, which also costs lives.” When a person is suffering with depression, “they actually want to be asked, and they want help.”

Posner’s center at Columbia has created over a dozen versions of a one-page pamphlet, each starting with a variation on a command geared to a different audience: “Ask a steelworker.” “Ask your spouse.” “Ask your foster child.” “Ask your coworkers.” “Ask your fellow officer.” It could be a coach checking in on a student athlete, or a person gathering the courage to ask a friend if something’s wrong.

Half the work is about preventing suicide, Posner explained, but “half of it is also about combating the stigma, which also costs lives.” When a person is suffering from depression, “they actually want to be asked, and they want help.”

“We have to have a public health approach, meaning we have to find people where they work, live, thrive and learn because many people don’t ever get to the doctor,” Posner said.

One perhaps unexpected place where Posner has been spreading the gospel of the Columbia Protocol is on construction worksites. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the rate of suicide in construction workers is five times the rate of fatal work-related injuries. “I’ve been talking to the unions for a long time. They said the safety check in the morning can be more than the hardhat,” Posner said.

Posner grew up in Miami, the granddaughter of businessman Victor Posner, who was known for his hostile takeovers of public companies.

“Everybody else went into business, but I was raised with these values of giving back,” Posner said of her family. “That fearlessness in the name of service was something, I think, that was fueled by my family background and also my Judaic values — that what matters is what kind of a person you are and giving back.”

In two recent phone interviews with JI, Posner spoke with the speed and intensity of a woman on a mission. She jumped from the Columbia Protocol’s benefits to its history to the intricate details of the scientific studies that prove it works.

She gets on Zoom calls with public health workers in China and Namibia and Italy in the middle of the night. She thinks big, and has no qualms about owning it.

“I’ve always been a high-impact person. How can I make the biggest difference if you live once, right? How can I relieve suffering and save lives?” These are the questions Posner asked herself early in her career.

As an undergraduate at Brown University, Posner first expected to be a lawyer working to free innocent people from prison. “That was my crusade at the moment,” she said, until a summer spent working with children in an inpatient mental health center convinced her that she should focus on fighting depression. She grew interested in the process of diagnosing mental illnesses. “It wasn’t so much mental health, but making a difference in the lives of people and particularly children,” said Posner.

She earned a Ph.D in clinical psychology at Yeshiva University’s Ferkauf Graduate School of Psychology, which awarded her a “distinguished alumna” award in 2007.

When asked about the genesis of the Columbia Protocol, Posner pointed to 2004, when the Food and Drug Administration commissioned her to do research about the links between prescription drugs and suicide.

She began working with the FDA after a controversial decision by the agency to put a “black box” warning on antidepressants noting that the drugs were associated with a slightly higher risk of suicide in children and young adults. But some studies have found that, after the prominent warning labels appeared, the use of antidepressants and talk therapy declined among young people, potentially leading to higher rates of suicide.

“We were worried we were in a horrible natural experiment: When you took these medications away from people, would the suicide rate increase? Yep, that’s what happened,” Posner noted. The FDA had no clear protocol on how to screen for suicide. But with Posner’s research, the FDA announced in 2008 that it would screen for suicide risk in all drug trials using the Columbia Protocol. A seminal 2011 study found that screening for suicide using the Columbia Protocol can help predict — and prevent — suicide.

“It’s much more detailed than what we were doing before,” Dr. Benjamin A. Toll, a researcher and psychiatrist at the Yale School of Medicine, told The New York Times in 2008 regarding the Columbia Protocol. “We used to ask, ‘Are you feeling down? Are you feeling sad?’”

The anti-smoking drugs Chantix and Zyban are the only drugs that have since had their black box suicide warnings removed, based on research that incorporated the Columbia Protocol. The warning remains on antidepressants, and Posner encourages people considering antidepressants to discuss with a doctor whether the benefits outweigh any potential risks.

The Columbia Protocol has spread “like wildfire,” said Posner, and as more institutions start using it, they produce more research showing that it works. One country that has introduced the Columbia Protocol nationwide — schools, governments, medical professionals — is Israel.

“Israel was one of my first great partners,” said Posner. “They were one of the first countries to show how we have to do it everywhere. That work started so many years ago, and that partnership with Israel and that ability to help save lives has been something I’m so grateful for and proud of.” She has worked with the Israeli Defense Forces to help identify soldiers at risk of suicide, and the protocol has also been used with Holocaust survivors in Israel.

“The Columbia Protocol has proven its power to bring diverse communities together for the single purpose of saving lives,” she said. Perhaps this could be true of global geopolitics, too: Posner is a Jewish American proud of her work with Israel, and she is also currently helping an Iranian hospital fully implement the protocol.

“Somebody who runs one of the hospitals or works at one of the hospitals said, ‘We’ve been using this for a long time, how can we do X, Y and Z?’ And I said, ‘Let’s get on a call, so we can figure out how to help your nation,’” Posner recalled.

Please log in if you already have a subscription, or subscribe to access the latest updates.