Courtesy

Nigun Quartet strikes a different note

The Israel-based group recently released its first album

Before the pandemic, an Israeli jazz ensemble was gaining recognition for its ecstatic live performances dedicated to interpreting incantational Hasidic melodies known as nigunim. The idea of crossing jazz with Jewish spiritual music isn’t a new concept, but the Nigun Quartet — saxophone, piano, bass and drums — stood out even in Israel’s crowded jazz scene thanks to its engaging shows approximating the loose, convivial vibe of a fabrangen — a kind of festive Hasidic gathering.

Polina Fradkin, who saw one of the group’s first performances and now helps with promotion, recalled being moved by the quartet’s on-stage approach. Before launching into a song, she said, the band members would detail the origin of each nigun — a Holocaust story, a circular dance, a meditation on joy — creating a transcendent interplay between music and source material that imbued the improvisation with deeper meaning. “You feel it,” Fradkin mused. “To hear the nigun after you hear the story is something else.”

Baruch Velleman was equally enthusiastic in a fall 2019 review for The Times of Israel, writing that the group was “one of the best jazz quartets I’ve ever come across” after he saw a show at an art studio in the West Bank settlement of Tekoa.

Recently, the Nigun Quartet independently released its first, self-titled album, including nine tracks that draw on a variety of nigunim such as “Shures,” “Shalom Aleichem” and “Shamil” — all of which derive from different Hasidic sects. Though the music was recorded in one live session at the beginning of 2019, there was a delay as the band sought donations in a crowdfunding campaign to recoup production expenses. The album was released a couple of months ago.

The album requires that the listener do some work on their own — such as reading the liner notes that give the backstory behind each tune — in order to at least simulate the experience of a live performance. But the sturdy arrangements and easy interplay suggest the group was more than ready to set these tracks down. The album invokes mid-period Coltrane, post-bop, funk, classical and other elements that in many ways represent the lingua franca of modern jazz — all filtered through a Hasidic folk prism.

For the four band members, that unique influence is what sets the Nigun Quartet apart. “The key to understanding our approach is to understand the function of the nigun,” Opher Schneider, the band’s 49-year-old bassist and resident mystic, told Jewish Insider in a Zoom interview from outside Jerusalem last month. “Hasidic niguns are a vessel, like, it’s an inner thing — they use the nigun to evoke a certain awareness. It’s not just a song.”

“We’re using what we’ve collected through the years — even now from contemporary music and grooves and certain harmonies — and using all that to amplify the inner function of the nigun,” Schneider added. “Sometimes it gets really astray. You know, people wouldn’t even recognize the nigun. But it’s there all the time. It repeats all the time. And that’s what fuels all the rest of the music that goes around it.”

As an example, he cites “Ashreinu,” the second track, which was inspired by a melody from the Breslov Hasidim about a group of Hungarian boys who narrowly escape the gas chambers at Auschwitz after they are found dancing defiantly on Simchat Torah. The song, featuring a skittering call and response between tenor saxophonist Tom Lev, 34, and pianist Moshe Elmakias, 24, functions much like a soundtrack to the imagined story.

Schneider played jazz professionally — both in New York and Israel — before he abandoned music altogether at 36 and devoted himself fully to Judaism. After a while, the urge to play returned as he began to learn more about traditional klezmer from Eastern Europe as well as other forms of Jewish music — and he slowly made his back back onto the scene.

A few years ago, he met two of the musicians who would later make up the Nigun Quartet — Lev and Yosi Levi, the group’s 53-year-old drummer — in a wedding band. They all agreed that there has to be more to music than securing the perfunctory gig. “We said, let’s do something, let’s figure out a way to play jazz while playing religious Jewish music.”

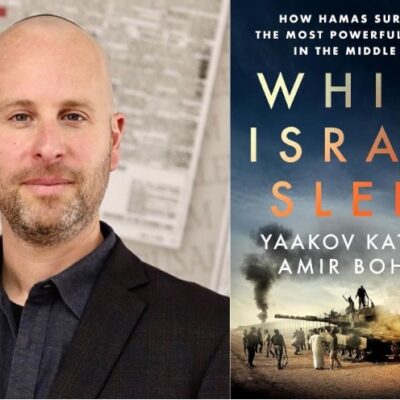

Nigun Quartet (Courtesy)

“We didn’t expect what came out of that,” said Schneider. “It’s something that totally blew our minds. It’s not what most people expect to hear.”

Fradkin agreed. “You feel all the musicians really connected to each other,” she said, “which is the first thing that I noticed when I saw them for the first time — connecting to each other and deeply connecting to the music on a really internal and spiritual level.”

Jazz has a long spiritual tradition including but by no means limited to some works by John Coltrane and Duke Ellington, so the impulse to draw from nigunim was appropriate. “Many people do combine between Jewish music and jazz or between any kind of spiritual music,” said Elmakias. “But this band has the combination of really good musicians with a huge amount of knowledge, of backgrounds for the songs and stories.”

“I always felt that jazz is a really, actually a deeply spiritual platform — it’s a very, very good platform in order to bring your spiritual connection into being,” said Lev, speaking on Zoom from outside Tel Aviv. “It happens right now, in the moment, on the spot. And that’s what jazz is about. Jazz is about bringing your spiritual entity into this music, right here, right now — that’s why it’s an improvised music.”

The Nigun Quartet brings that ethic into new territory, according to Lev. “The thing with this band is that it marriages the whole idea of jazz but it takes it to a much deeper place,” he said. “You can have almost a heavenly presence come down and be present in the music in the here and now.”

Lev, of course, wasn’t speaking from recent memory, as Israel has been on intermittent lockdown since the pandemic hit last March. The group hasn’t played together for some time. Elmakias is now in Boston, where he is studying to receive his master’s degree in jazz piano at the New England Conservatory of Music. In the Zoom call, each musician was sequestered at home, waiting out the coronavirus crisis.

Still, Elmakias, a Jerusalem native, says the band has much more in store as they make plans to draw from an extensive song book that came together after several rehearsals and performances. The hope, according to Elmakias, is to record at least two more albums, which will document the 20 or so arrangements they haven’t yet released.

“That’s what’s beautiful about these niguns. We have so much material to work with,” he said. “It’s endless.”