Pivoting from the runway to COVID relief

When the coronavirus hit, modest fashionista Adi Heyman refocused the Jewish Fashion Council to provide emergency assistance

Suffice it to say that 2020 has not gone the way Adi Heyman expected.

Following New York Fashion Week in February, Heyman jetted off to London to promote her nonprofit, the newly formed Jewish Fashion Council. Days later, she was back home in New York, and within the month she had tested positive for COVID-19.

Heyman’s London engagement was at the Leo Baeck Institute, a Jewish cultural and academic hub, to discuss tzniut — modest — fashion. Heyman, who wears a blonde wig and covers her elbows and knees, was described on the institute’s website as a “fashion stylist turned blogger.”

But neither of those descriptions fully capture her — she’s a trendsetter and a trendspotter, an advocate for equality and against antisemitism, a community builder and a social media influencer who sees her modesty as something to embrace, instead of to overcome. She is not an Orthodox woman who happens to buy cute skirts; she is a Fashion Week regular who has been photographed for glossy photo spreads in the “street style” section of upscale magazines.

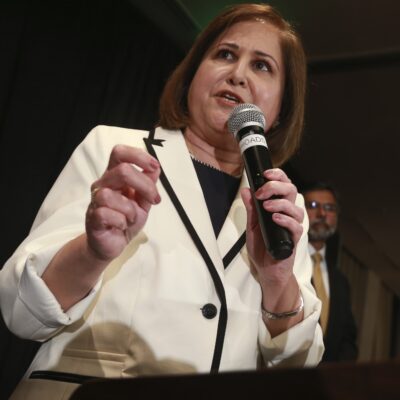

Adi Heyman

In March, the Jewish Fashion Council was Heyman’s one-woman project, meant to connect Jewish professionals in the industry, and support Jewish students at top fashion schools. The speech in London was supposed to serve as an unofficial kickoff for the organization.

Then the pandemic hit. Many in the fashion industry fled Manhattan for their country homes. Students at FIT and Parsons returned home when their New York campuses shuttered. The coronavirus took aim at New York City, and at Heyman, who recovered after a week of mild flu-like symptoms. But she saw that things were getting worse for so many others in her community.

“It was insane, the amount of suffering,” Heyman said in a recent phone interview from the Hamptons, where she is spending the summer with her family. With “kids out of school, abuse rates were going up,” she said, and “our Holocaust survivors needed to be fed. The elderly Jews in my community weren’t leaving their homes at all, and they had no way to get medications.” With the fashion industry on pause, Heyman’s new nonprofit had little to do. So she converted it to serve as a vehicle for COVID relief efforts, both in and outside the Jewish community.

Even though Heyman is still running the organization alone, she said that operating under the Jewish Fashion Council banner “sounds more legit than one person,” which convinced others to get on board. The organization has hosted five clothing and food drives since May, most of which were geared toward Jewish communities — but open to non-Jews as well — in Manhattan, the Hamptons, Los Angeles, the Catskills and Long Island’s Five Towns.

Heyman said that she was wary of asking people to donate money because it was “uncertain times, and I wanted people to be able to connect through the giveback and the inspiration and the connectivity of community,” she explained. She organized volunteers to pick up donations from the homes of individuals who were concerned about going out. Heyman observed that many people were so nervous about the coronavirus that they didn’t know how to volunteer. “I felt like we were helping the people that we were enabling to give, because people weren’t sure how to at that point,” Heyman said.

Getting people to care enough to volunteer or donate remains a major hurdle. “We are basically in a recession,” she said. “How is this not alarming to people? How is everybody wanting to have this great summer without awareness of this?”

The conversation about reopening schools devastates Heyman more than any other topic. She recalled an op-ed by a teacher who called for schools to operate virtually, saying students and teachers are safer at home. “I circled it, I posted it on my [Instagram] stories, and I said, ‘Who is safe?’ Maybe this teacher is safe, but if you teach in a public school, your students are not safe,” she said. “What about the ones sleeping in parking lots to get Wi-Fi?… How many don’t have meals or are being abused?” The Manhattan private school where Heyman’s son attends will have in-person learning this fall, while New York City public schools will be mostly or entirely online. “If we can go to liquor stores, and these can be essential… schools should be essential,” Heyman added.

The pandemic has heightened many people’s emotions, particularly Heyman’s, who takes people’s actions — or inaction — personally. “Our leaders have failed us across the board,” she said, but “for me, the worst part is pinning the statement on vote change in November… we have people that need help… It’s barely August, should we let them suffer for another few months until everybody can vote?”

***

Heyman’s story begins far from Manhattan, and even farther from the religion that has come to define her life, her career and her family. She was born into a religious Christian family in San Antonio, Texas. She and her siblings were home-schooled as children. When she was in her teens, the family converted to Judaism.

“My parents were definitely on a spiritual journey,” Heyman said. Her mother came from a family of preachers, while her father grew up secular. “When he came into Christianity, I think there was a lot of questions.” Those questions eventually “led them outside of Christianity to a few different religions, and ultimately Judaism,” Heyman explained.

The family moved to South Florida and Heyman enrolled at Hebrew Academy in Miami Beach. She legally changed her name to Adi, but still went by her birth name, Amber — and learned later that members of their synagogue thought at first that Heyman’s family was part of the witness protection program. “We’re all very blonde and we didn’t know Hebrew,” Heyman said, laughing, “so I guess it makes sense.”

Heyman and her siblings were happy to convert. “As a teenager, what I think was very shocking to me, I met so many people who said to me, ‘Why would you want to be Jewish? I would never choose to be Jewish,’” Heyman recalled. “I think it was shocking for me to hear that people who were so committed to this lifestyle, that is very much dictated by religion and inheritance and tradition — which is so rich and so beautiful — [would] say, like, ‘I don’t know if I would choose it.’” But Heyman never questioned her connection to Judaism. “If it’s not something I wanted to do, I don’t think at 38 years old I’d be doing this.”

***

At 21, Heyman got married and started wearing a wig to cover her hair, as stipulated by Jewish modesty laws. Soon after, she got her first job in fashion, as an assistant to an editor at a fashion magazine. “I didn’t know much about fashion,” Heyman said, but she knew she wanted to be in Manhattan, and “it just happened to be that that’s the job that I could make enough to stay in the city.”

Fashion “was a great fit creatively for me,” she said. “It is still so inspiring and so emotional.” She took up styling, and soon saw that her own styles were being photographed and printed in publications like Vogue — “the fashion bible,” noted Heyman.

In 2010, she created a Facebook page called Fabologie, where she posted photos of fashionable outfits that were also modest. The page gained a following and eventually spawned a blog, which caught the attention of The New York Times; the newspaper featured a profile of Heyman under the headline, “Modesty Is Her Best Policy.” Fabologie showcased modest trends with articles written by Jewish women, whom Heyman wanted to help find success in the competitive industry.

She shut down the blog in 2015 when the work began to feel overwhelming and she wanted to spend more time at home with her young son. She started freelancing, including a stint writing for Ivanka Trump’s website. She briefly gained viral notoriety in early 2017 after sending an interview request to New York chef Angela Dimayuga, who turned Heyman down in a heated anti-Trump Instagram post.

Adi Heyman

She has since supported and helped develop the Jewish life center at the Fashion Institute of Technology, organizing “Faith in Fashion” summits with Jewish speakers from the industry, and working with designers like Elie Tahari to host graduation brunches with kosher food so Jewish students could attend and network.

At these events, Heyman always gets asked how her faith has affected her career. “My thing is always, why wouldn’t it be positive? We all adhere to diets. We all choose places to live. We all choose our lives, and we’re empowered by those choices,” she said, “and we’re willing — most of us — to work really hard for those lives because we see the beauty in them.”

She does not reserve her Instagram, with nearly 50,000 followers, for just fashion posts. She has recently taken to calling out antisemitism, which she believes is a glaring blind spot in the fashion industry. Heyman said fashion writers have “been very good to me” in covering modest fashion trends, but she has not seen them speak up when a number of influential figures have publicly shared antisemitic views. By Heyman’s count, Vogue “did over 100 social media posts on anti-racism and BLM, and they gave zero to antisemitism.” In July, Vogue Arabia’s Instagram shared a map of Israel labeled only as “Palestine,” which Heyman took a screenshot of and posted. “I’m surprised my industry wants to just sit down and turn an eye to this,” she said.

But it’s not all bad news. Vogue UK published an op-ed at the end of July about the need to address antisemitism. Volunteers helped make her COVID relief efforts a reality. And there’s more to come, because she is not a person who knows how to sit still. “I love a challenge,” Heyman said. Next up? Working with an organization called Struggle to Save Ethiopian Jewry to help Jews in Ethiopia access clean water. “I just think it’s going to be a beautiful thing.”

This article was updated for clarity at 1 p.m. on 8/3/2020.