wikipedia

Unpacking the many lives of Isaac Stern

Author David Schoenbaum sifted through thousands of papers to research his new book on the legendary violinist

David Schoenbaum spent nine months digging through dozens of boxes of personal papers belonging to the world-famous violinist Isaac Stern in the archives of the Library of Congress.

Among the thousands of artifacts, Schoenbaum discovered 18 invitations to the White House; correspondence with Britain’s Prince Charles, Henry Kissinger and a fifth grader from Oregon; and a calorie-logging calendar Stern discarded after two days.

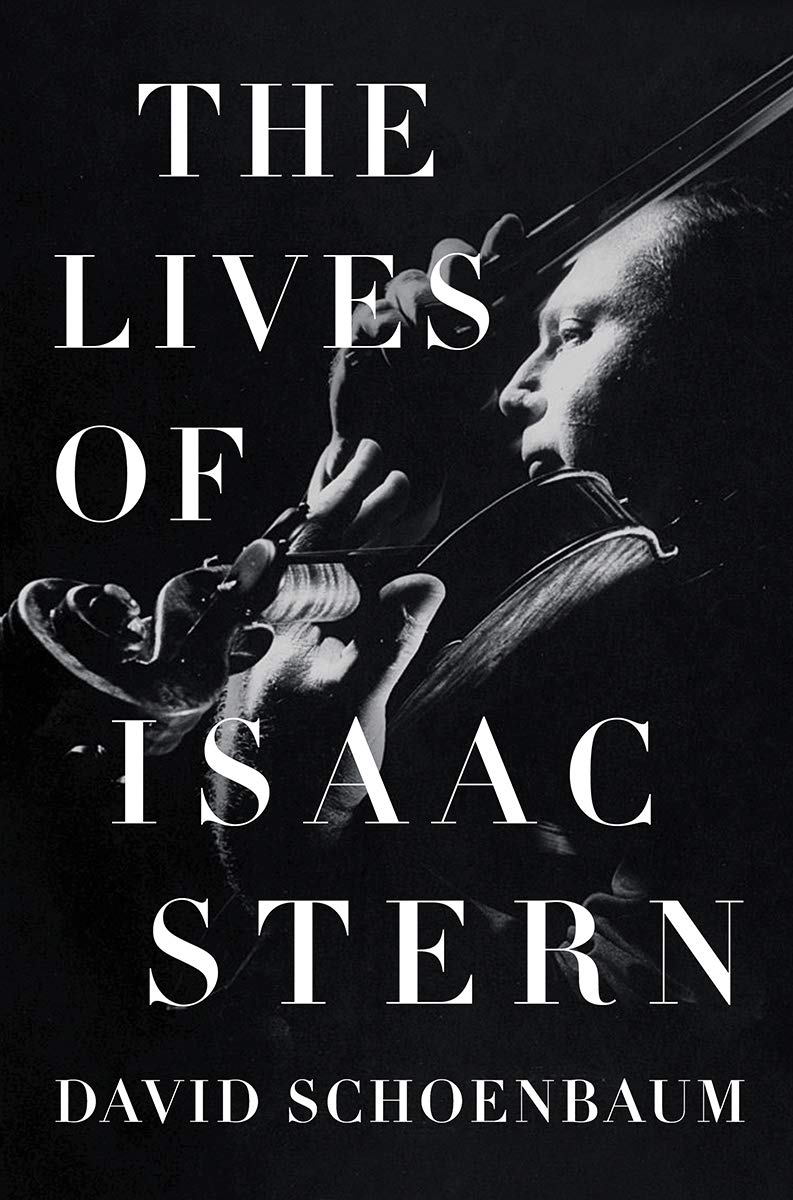

Schoenbaum’s extensive research ultimately produced his newest book, The Lives of Isaac Stern, a close examination of the very public activities of one of the most famous violin players to ever live.

“Every day was a surprise,” the author said of his time in the archives, noting that the trove of documents had never been sorted or catalogued. “I had no idea what I would find when I opened one of those boxes.” What emerged was a chronicle that led Schoenbaum, 85, to divide his book, and Stern’s life, into four categories: immigrant, professional, public citizen and chairman of the board.

“There was a personal history and a professional history and a public history and a philanthropic history,” he said. “He did more and different than any other player I guess since [19th-century Hungarian violinist] Joseph Joachim.”

Stern, who died in 2001, was born in what is now Ukraine, and moved with his Jewish parents to San Francisco when he was a baby. At age 8 he began studying the violin, at 10 made his debut with the San Francisco Symphony and by 18 he was criss-crossing the United States on tour. At 23 he took the stage triumphantly at Carnegie Hall — an event he referred to as his “professional bar mitzvah” in the 1999 memoir he wrote with Chaim Potok.

While Stern quickly became one of the most in-demand violinists around the world, Schoenbaum focuses much of the book on his societal and philanthropic ventures, including his love for and extensive ties to the State of Israel, “where audience after audience overflowed the available space,” he writes. “The self-assured informality of Israeli audiences in shorts and khaki shirts, score in hand, immediately enchanted him.”

Isaac Stern on his way to a concert in Caesarea, Israel, in 1961.

“At some point he counted up his visits to Israel and it was in the hundreds,” Schoenbaum told JI. “He was attached to the place… it captured his imagination for the same reason it captured the imagination of all American Jewish liberals. It was just a very appealing kind of place,” he added. “Of course he was received like a national hero.”

Stern visited so often that he became the centerpiece of a full-page ad for El Al in 1993. He met with Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, developed a close friendship with Jerusalem Mayor Teddy Kollek, and repeatedly canceled concerts elsewhere to rush to Israel and entertain its war-weary citizens, in 1967, again in 1973 — and at an infamous 1991 concert interrupted by an air raid siren, and carried out with the audience wearing gas masks.

Beyond his concerts there, he also left a legacy in the Jerusalem Music Centre, the institution he dreamed up, fundraised for and inaugurated in 1973. He served as president of the America-Israel Cultural Foundation, was a founding member of the National Council on the Arts, and led a campaign to save Carnegie Hall in the 1960s, becoming president of the Carnegie Hall Corporation from 1960 until his death.

Schoenbaum, a prolific author whose most recent book was a 700-page treatise titled The Violin, was very familiar with Stern’s star turns and extensive time in the spotlight. But even he was surprised at the breadth and variety of the violinist’s public connections.

“What impressed me is the number of people he knew and connected with,” Schoenbaum said, “and the sheer physical range of his life.” Stern “knew people you wouldn’t imagine, and was quite generous about maintaining connections over the decades,” he said. He played for presidents and prime ministers and hobnobbed with Frank Sinatra, the philosopher Isaiah Berlin and Abe Saperstein, the founder and coach of the Harlem Globetrotters, but also kept in touch with the conductor of the local orchestra in Sioux City, Iowa, and answered mail sent by curious schoolchildren.

In 1993, he reached out to a veritable who’s who of prominent figures to drum up support for Kollek ahead of his final and unsuccessful run for mayor of Jerusalem. Stern hit up actor Kirk Douglas, philanthropist Charles Bronfman, publisher Marty Peretz, banker Felix Rohatyn and future World Bank Group president James Wolfensohn for donations.

“He would have been a success in business, he would have been a success in politics, he would have been a success in diplomacy,” said Schoenbaum. “He was just that kind of guy.”

And Stern did lead a diplomatic life of sorts, often touring the world as a performer with a barely disguised agenda. In 1956, Stern became the first American musician to perform in the Soviet Union, in 1961 he was sent by the State Department to perform in Iran and in 1979 he toured China, just as the country was opening up to the Western world.

But there was one place Stern steadfastly refused to take the stage throughout his life: Germany. He famously never held a concert there, citing the painful and visceral atrocities of the Holocaust. He did, however, encourage other artists to perform there, and held a series of master classes in Cologne in 1999, two years before his death.

Schoenbaum, who has written extensively about Germany, only glancingly references Stern’s complicated relationship with the country in the book.

“It came up in every interview. He was always asked about it and he always said the same thing,” Schoenbaum told JI. “He liked to like his audience.”

In 1986, however, he made headlines when he chose to play at a Harlem church despite more than a third of the accompanying New York Philharmonic boycotting the concert because a minister at the church had refused to denounce Louis Farrakhan over his many antisemitic remarks.

By the time he died in 2001, Stern had become a household name, racking up accolades, awards, achievements and even the presidential medal of freedom. His music can be heard in the iconic 1970 film “Fiddler on the Roof” and a documentary about his visit to China won an Academy Award in 1981.

But he never quite forgot his humble roots. After all, at his 80th birthday party, his friend — former MLB commissioner Fay Vincent — recalled: “He once told me to think of him as a fat little kid from San Francisco who loved Joe DiMaggio.”